On a sun-drenched afternoon in the Bahamas, my friends and I sailed out for what we thought would be a routine spearfishing trip. We anchored off the remote southern tip of Abaco, between Sandy Point and Hole in the Wall, and found ourselves alone in the blue-green expanse. As we freedived beneath its surface, the clear water was alive with groupers, cubera snappers, and reef sharks.

My buddy, Jon, landed a shot on a large black grouper. The wounded fish fled, leaving a ribbon of blood as it swam disoriented for cover under a rock 40 feet (12 meters) down. I knew my next moves: Dive, finish the job, and bring up the grouper.

As I closed in, a shark darted between us and spooked the grouper from its hole. The shark took a swipe but failed to grab the fish. I took a shot and missed the dying yet still agile grouper. Another shark made an unsuccessful lunge at the fish while I reloaded my pole spear. The frenzy was fully on. Just as I prepared to aim again, I felt a jarring impact. I was confused and thought my head had struck a rock or the seafloor. My focus shifted from hunting to survival as reality dawned: The shark had closed its jaws on the side of my skull.

I dropped my pole spear and surfaced, asking Jon if I had been bitten. His urgent, “Yeah, man, we gotta go!” confirmed what my body already knew. Later he told me another shark followed my ascending blood trail, and he swam down to intercept a potential second attack.

Sharks aren’t inherently aggressive toward divers, but like us chasing the grouper, they seize opportunities when presented.

The water clouded crimson as we tried to gauge the extent of my injuries. The shark left about 20 teeth marks and 22 inches (56 centimeters) of lacerations on my head and face.

Our friend in the nearby dinghy spotted us and pulled anchor, speeding over to haul me out of the water. We grabbed the medical bag and pressed QuikClot bandages to my wounds. After the tense 10-minute ride to the sailboat, we wrapped my head more securely. The bleeding subsided, but we remained isolated and miles from help.

Aboard the sailboat, we radioed on channel 16 and then called DAN’s emergency hotline. As soon as their medic picked up, DAN brought control to the chaos. They asked questions about my injuries and situation and began organizing an emergency response. Their team directed me to the nearest medical facility in Sandy Point on Great Abaco.

As our captain sailed toward port at six knots, we encountered two whale researchers who kindly offered a ride on their faster vessel, helping me reach shore sooner.

Sandy Point Clinic sat just around the corner from the tiny town’s docks. Thanks to DAN’s advance coordination, the nurse and doctor were ready upon arrival. Nurse Lightbourn’s staff did a great job administering oxygen and IVs. DAN stayed on the line and consulted with the treating physician. Together, they determined that medical evacuation was necessary.

DAN honored my preference for evacuation to my home state of Florida rather than Nassau. They helped us navigate the paperwork, including customs preclearance and a Fit to Fly form, and called a ground ambulance to take me to Abaco’s Marsh Harbour Airport.

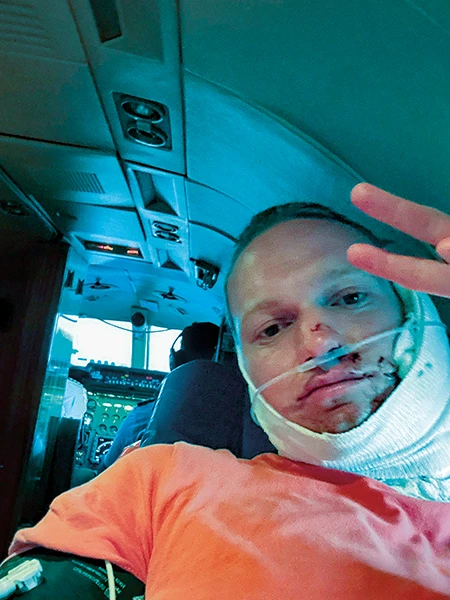

Two emergency medical technicians (EMTs) met us at the airport and transferred me onto the air ambulance DAN commissioned for the half-hour flight to Fort Lauderdale. The private jet, designed for medical efficiency rather than luxury, felt surreal — my only fellow passengers were the medics attending to me. We touched down in Florida at sunset.

DAN had already arranged my ground transport and admission to receive definitive treatment at Memorial Regional Hospital. I was discharged around 2 a.m. and made it home by 3:15 a.m. My recovery went well. I had my stitches out in five days and the staples out in 10.

Considering that a shark bit my face, I count myself lucky. The attack occurred around 1:30 p.m. in remote Abaco. I was admitted to a hospital in the U.S. less than seven hours after calling DAN. Proper first aid and medical care plus the quick actions of my buddies contributed to this best possible outcome. DAN made all the difference, however, as their dedicated support and direction kept that whirlwind day on course.

When I started spearfishing eight years ago, and even when I joined DAN last year, I never imagined something like this could happen to me. When it did, DAN was there. From my first call to the hotline, their team seamlessly handled my medical transportation and expenses, allowing me to focus on recovery.

I recommend DAN to every diver, including freediving spearos. Even if you’re not on scuba, DAN can still be your lifeline in an emergency.

I have retired the mask the shark punctured with its bite and plan to spearfish again with a new one once I’m cleared to dive. I share this story not to deter anyone from spearfishing or sharks but to remind even experienced divers that the ocean is unpredictable. Venturing beneath the surface means accepting the risk and responsibility that anything can happen. With preparation and DAN on your side, even a chance encounter with a shark’s jaws can renew your respect for the sea and desire to return to its depths, dive after dive.

© Alert Diver – Q4 2025