Effects of coral restoration on wave attenuation

At 18 feet (5.5 meters) above sea level, Solares Hill is the highest point of land in Key West, Florida. Yet that lofty elevation would not have measured up to the swells that Hurricane Helene produced in 2024 had the offshore waves reached land. It didn’t need to, as a coral reef structure 7 miles (11 kilometers) away at Eastern Dry Rocks dissipated more than 90% of the wave energy.

“Without the barrier reef system, much of the Keys would be exposed to the full brunt of ocean swell,” said Jim Hench, an associate professor of oceanography at Duke University who led the research. “But the reefs, through their complex structure and frictional properties, interact with the waves, converting wave energy into turbulent energy and then heat. That’s the dissipation mechanism.”

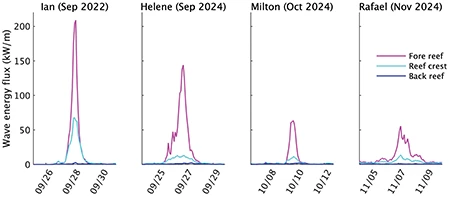

An offshore buoy in more than 300 feet (91 m) of water at Satan Shoal, 8 miles (13 km) southwest of Eastern Dry Rocks, measured 19-foot (5.8-m) swells as Helene passed the Keys on Sept. 26, 2024, as a Category 1 storm. One wave peaked at more than 32 feet (9.8 m). Helene was one of four hurricanes that impacted the Florida Keys in consecutive months that fall.

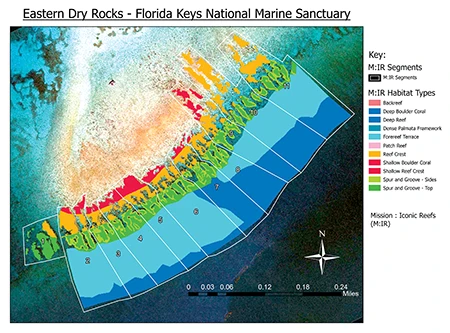

Researchers had studied the physics of wave mitigation along flat, sandy beaches, but relatively little work had been done applying theories to the steep, complex topography of coral reefs along the Keys, particularly under extreme wave events. In August 2021 Hench deployed oceanographic sensors across Eastern Dry Rocks to calculate what scientists call wave attenuation — the reduction in energy as waves interact with shallow bathymetry and rough bottom topography.

The array of 14 sensors recorded wave energy on a 0.3-mile (0.5 km) transect across the reef as the waves broke and dissipated from front to back. It did not take long to confirm a hypothesis.

In 2022 Hurricane Ian blew by the Keys on a trajectory that provided the perfect storm for quantifying the phenomenon. As the waves began to interact with the shallow reef structure, the reef swallowed their energy.

“When the water gets shallow enough, waves break,” Hench explained. “We know that, but what surprised me was the amount of dissipation across the shallow fore reef, characterized by ridges of reef formed by coral spurs separated by channels or grooves before breaking.”

Hench used data from Hurricane Ian to compute wave energy fluxes, which combine wave height and wave period (the time between wave crests) into a single value in terms of kilowatts per meter (kW/m). The fluxes decreased from 220 kW/m on the fore reef to less than 5 kW/m on the back reef, representing a 97% reduction. Similar reductions were seen for the four hurricanes in 2024.

These results demonstrate the powerful wave dissipation capabilities of a living reef, underscoring the need for restoration in an era defined by multiple challenges.

“As the waves approach the reef, the wave orbitals are really energetic while interacting with the coral roughness,” Hench said. “That’s a really good recipe to dissipate wave energy in a relatively small area. This finding has significant implications for where reef restoration might be best suited to maximize wave attenuation, taking advantage of when the waves are most energetic and using that enhanced roughness to dissipate the wave energy.”

Eastern Dry Rocks, a protected marine sanctuary, features stunning spur-and-groove formations that have historically supported large thickets of elkhorn and staghorn corals as well as massive star coral colonies.

“The people who go out there are astounded by the amount and variety of fish and marine life they see,” said Leslie Levis, a dive shop owner in Key West. “There is everything from sharks to eels to turtles and every kind of fish.” Each day during the summer, Levis’ shop will ferry 15 to 18 divers to the site.

Over time, reef-building corals at Eastern Dry Rocks have declined but are now being restored as part of Mission: Iconic Reefs, an effort led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It is critical to understand the effects of coral restoration and associated changes in reef roughness on wave attenuation.

“There is much we still don’t know about the interactions between rough, multiscale reef roughness and waves,” Hench said, “and how that energy is dissipated and which coral restoration strategies will be most effective under a range of wave conditions.”

Deploying a dense array of oceanographic sensors across a coral reef presents several challenges. Traditional oceanographic research methods employ over-the-side methods where sensors are dropped or lowered from a surface vessel. This approach, however, would most certainly damage both the reef and the sensors.

For this project, the team made extensive use of scientific diving techniques to place sensors in precise locations away from living substrate and to secure them to the bottom to survive large storm events.

The sensor array also requires periodic servicing to download data, install new batteries, and clean biofouling. With many sites to cover and strict restrictions on anchoring within the marine sanctuary, the team used diver propulsion vehicles (DPVs) to make the project feasible.

“With short weather windows offshore and lots of underwater sites and sensors, DPVs were a game changer for this project. They let us complete work that we could not have done otherwise,” said Ben Edmonds, a field specialist with the Mission: Iconic Reefs team.

Data from all the storms will serve as a baseline to calculate changes in wave energy dissipation as Mission: Iconic Reefs restores coral over the next 20 years. The team outplanted more than 11,000 coral fragments at Eastern Dry Rocks over the first five years of the program, but the marine heat wave in 2023 posed a setback.

NOAA managers are undeterred, however, and the current outplanting season will feature thousands of corals strategically selected for these efforts. The corals being planted include those with tracked survival and heat tolerance, while contributing to ongoing research to identify resilient species and genotypes for future restoration.

“Restoration moving forward will be more targeted,” said Katey Lesneski, the Mission: Iconic Reefs research and monitoring coordinator. “We will focus on areas where corals have survived past heat stress and expand those resilient populations. Practitioners will also be incorporating more resilient species and genotypes at other sites. Coral reefs don’t recover overnight, but informed, adaptive restoration gives them a fighting chance for the future.”

Mission: Iconic Reefs hopes to expand the monitoring program to other locations, adding control sites that are not being restored as well as inshore stations.

“The longer-term goal is to get sensors set up from the shore to the reef,” said Andy Bruckner, Mission: Iconic Reefs research coordinator. “Right now we’re only looking at that first buffer, and waves may build up again because the wind is still there. We don’t know how that changes all the way to the shoreline.”

Funding for this research came from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, facilitated by the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation and permitted by Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS-2021-122) as well as the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Explore More

Find more about Beauty and Brawn in this bonus video.

© Alert Diver – Q4 2025