SU NOMBRE ERA TOKITAE, que significa “bonito día y hermosos colores” en la lengua salish de la costa. La Nación Lummi la conoce como Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, que es una referencia histórica al área de Penn Cove, donde fue capturada junto con otras jóvenes orcas (Orcinus orca) residentes del sur en agosto de 1970 cerca de Whidbey Island, Washington, cuando tenía unos 4 años.

La Nación Lummi y grupos de conservación, activistas de derechos animales y otros lucharon por años para liberarla de su cautiverio y tenían la esperanza de llevarla de regreso a un corral marino en sus aguas de origen en el mar Salish, pero la querida orca de 57 años falleció el 18 de agosto de 2023 en el Miami Seaquarium de Florida, donde había vivido por 53 años desde su captura, actuando para las multitudes como Lolita.

Cuando Tokitae llegó al Seaquarium en 1970, se unió a una orca macho mayor que se llamaba Hugo, que también había sido capturado en el estrecho de Puget y enviado al Seaquarium dos años antes de la llegada de Tokitae. Ambos eran miembros del grupo L residente del sur en peligro de extinción.

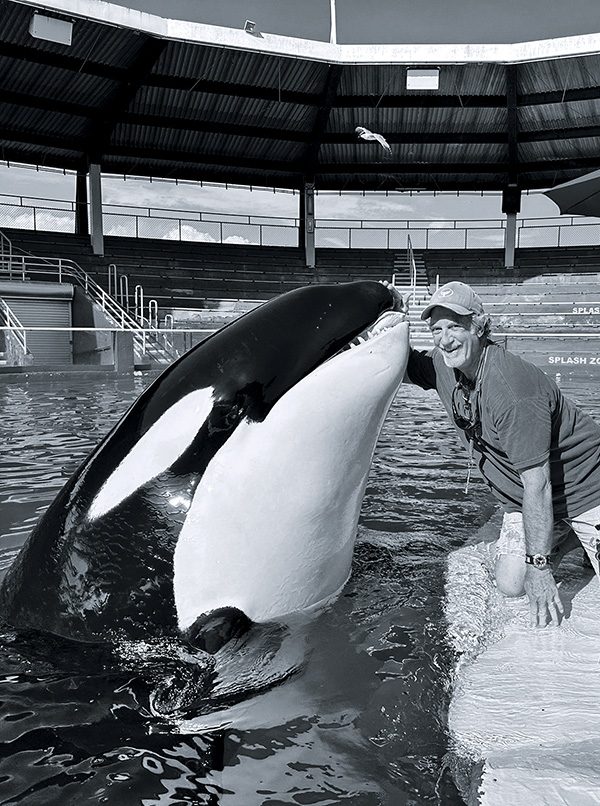

Con un enfoque en mejorar la salud y el bienestar de los mamíferos marinos bajo el cuidado humano, la conservación de poblaciones silvestres y el apoyo a redes de varamientos mundiales, Stephen McCulloch ha trabajado por cinco décadas tanto en la industria zoológica como en comunidades de investigación y conservación de todo el mundo. Su relación con Tokitae duró 50 años. CORTESÍA DE STEPHEN MCCULLOCH

De 1965 a 1976 más de 100 orcas fueron capturadas en Penn Cove, Washington. Diez de estas orcas fueron vendidas a parques marinos y el resto de ellas fueron puestas en libertad. Al menos cinco orcas murieron durante esta y otras dos operaciones de captura. © WALLIE V. FUNK

Hugo murió en 1980 por lesiones autoinfligidas como resultado de un aneurisma cerebral, probablemente tras golpearse la cabeza reiteradamente contra la pared del tanque. Después de su muerte, Tokitae nunca vio ni escuchó a otra orca, y tuvo una existencia solitaria en ese sentido. Sus únicos compañeros eran cetáceos más pequeños que vivieron y actuaron con ella a lo largo de los años.

Para los activistas, las décadas que Tokitae pasó aislada de otras orcas y vivió en un recinto pequeño y anticuado es otro ejemplo de explotación animal. Aunque los caminos divergen en lo que respecta a la mejor manera de ayudar a las orcas a prosperar en entornos zoológicos y en estado salvaje, los valores compartidos y un diálogo respetuoso son los mejores medios para superar las diferencias filosóficas significativas. Estos debates incluyen la ofensiva brutal de las pesquerías y las prácticas de caza de ballenas actuales que dan lugar a la matanza innecesaria de miles de ballenas cada año.

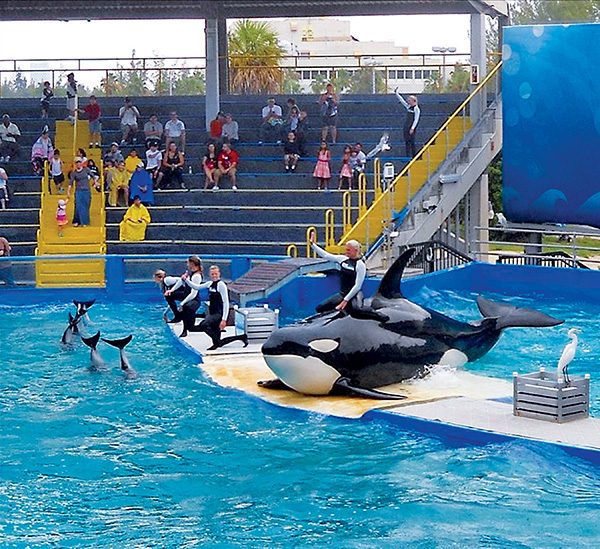

Los parques marinos que se esfuerzan por satisfacer las necesidades de los animales a menudo recorren una línea imperfecta entre la ética contemporánea, la educación, la investigación y los objetivos de conservación. Los cambios graduales para optimizar la cría, los diseños de recintos y las prácticas de enriquecimiento pueden mejorar el bienestar cotidiano dentro de los límites de los entornos de cuidado humano. Es posible que los establecimientos que no puedan satisfacer adecuadamente las necesidades de los animales en cautiverio deban mejorar o ser eliminados gradualmente —una lección del Miami Seaquarium y la vida y la trágica muerte de Tokitae—.

Tras la muerte de Hugo en 1980, Tokitae fue ubicada con otros cetáceos pequeños, pero siguió siendo una orca solitaria hasta su muerte en 2023. © ALLAN WATT

Apenas cinco días antes de su muerte, el equipo veterinario de Friends of Toki informó que se encontraba saludable. Su condición física, su comportamiento y sus análisis de sangre estaban dentro de los parámetros normales. Estaba respondiendo favorablemente a los tratamientos en curso para tratar una infección respiratoria crónica y una enfermedad micótica. Sin embargo, en las siguientes 36 horas presentó síntomas de malestar gastrointestinal y dejó de comer. Debido a que los mamíferos marinos son expertos en ocultar enfermedades en estado salvaje, no comer a veces es el primer indicio de que algo no está bien.

El equipo veterinario desarrolló un plan de tratamiento inmediatamente para rehidratarla mediante fluidos subcutáneos, administrarle medicamentos, tomar una muestra de sangre fresca y realizar un ultrasonido en su región abdominal. El viernes 18 de agosto a las 10 de la mañana, el nivel del agua de su estanque fue reducido gradualmente para facilitar el tratamiento. Los protocolos se conocían perfectamente de cuando había recibido un tratamiento similar en octubre de 2022 por un período de ocho días tras haber dejado de comer.

Los entrenadores y el equipo veterinario monitorearon la respiración y la frecuencia cardíaca de Tokitae de forma ininterrumpida mientras descansaba tranquilamente en el fondo del estanque en agua hasta la cintura. Una vez finalizados los tratamientos, el nivel del estanque se fue aumentando lentamente. No obstante, en esta oportunidad no se recuperó por completo. En lugar de reanudar su patrón de nado habitual, se la veía aletargada y desorientada, inclinada hacia la derecha e incapaz de manejar su entorno. El equipo veterinario revisó los análisis de sangre de inmediato, que indicaron que estaba experimentando una insuficiencia renal aguda y requería tratamiento adicional.

Con varios miembros del personal junto a ella en el agua para brindarle apoyo, el nivel del agua del estanque se redujo una vez más. Esta vez fue colocada en una camilla para poder estabilizarla mejor. Durante las horas siguientes el equipo veterinario le administró más fluidos mientras sus entrenadores la reconfortaban y monitoreaban sus signos vitales. Pero a pesar de sus mejores esfuerzos, Tokitae falleció en los brazos de sus entrenadores, rodeada del personal de atención de animales y otros individuos que habían estado trabajando para reubicarla en sus aguas nativas.

A pesar del dolor y la gravedad de ese momento, el equipo respondió rápidamente para proteger la integridad de sus restos y preservar las delicadas muestras biológicas que ayudarían a determinar su historia de vida y confirmar la causa de muerte. Mientras Tokitae estaba siendo asegurada, el personal de entrenamiento desvió su atención a su único compañero de estanque que quedaba—un delfín de flancos blancos del Pacífico macho de 40 años llamado Li’i, que esperaba su regreso del otro lado de los mamparos estancos—.

En una hora Tokitae fue elevada del estanque donde había pasado 53 años y fue bajada con cuidado hacia un contenedor hermético. Fue conservada en hielo y colocada en un camión frigorífico para ser trasladada a la Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria de la Universidad de Georgia (University of Georgia), donde un equipo de patólogos veterinarios de mamíferos marinos pasó casi 20 horas realizando un examen forense detallado.

Si bien la causa de muerte exacta demorará meses en procesarse y confirmarse, los resultados preliminares de la autopsia macroscópica fueron compatibles con una insuficiencia renal aguda y confirmaron el alcance de las lesiones pulmonares vinculadas a su infección pulmonar crónica.

La muerte de Tokitae afectó profundamente a sus cuidadores, la industria zoológica, activistas, conservacionistas y grupos indígenas, en especial la Nación Lummi. Si bien existen diferentes perspectivas respecto de sus décadas en cautiverio, hay una veneración compartida por estos seres sintientes. La conexión ancestral de la nación Lummi con Tokitae representa el papel cultural más amplio de las ballenas para los pueblos indígenas. Su cautiverio rompió vínculos sagrados entre la naturaleza y la comunidad.

El 20 de septiembre un anciano de la Nación Lummi acompañó las cenizas de Tokitae desde Georgia hasta Bellingham, Washington, donde miembros de la tribu hicieron una ceremonia privada en aguas sagradas y devolvieron sus cenizas a sus aguas nativas. Tienen pensado realizar una ceremonia pública para honrar a Tokitae más adelante.

Después de pasar 35 años en Seaquarium, Li’i actualmente está en SeaWorld en San Antonio, Texas, donde se unió a otros delfines de flancos blancos del Pacífico el 25 de septiembre.

Algunas personas sugieren que el legado de Tokitae puede impulsar a desarrolladores, filántropos y la Ciudad de Miami a crear One Ocean, One Health Center (Un océano, un centro de salud) en lugar del Miami Seaquarium. Un centro de rescate de mamíferos marinos y hospital escuela para generaciones futuras de veterinarios y científicos que se reúnan y colaboren sería un legado apropiado y una vía de progreso.

Los humanos tenemos una obligación de anteponer las necesidades de los animales con los que compartimos la Tierra a los intereses comerciales. Los zoológicos y acuarios responsables y bien manejados representan un recurso fundamental para el futuro de la preservación de especies. La idea de que los zoológicos y acuarios sean un depósito definitivo del ADN de criaturas en peligro de extinción masiva en estado silvestre es una perspectiva aterradora.

La muerte de Tokitae debe inspirarnos para evaluar nuestras relaciones con los animales y entre nosotros. Todos compartimos la responsabilidad de ser buenos guardianes de las criaturas con las que compartimos el planeta.

© Alert Diver - Q4 2023