Wreck diving became the rage of dive tourism in the wake of the 1977 blockbuster movie The Deep (. As a budding dive entrepreneur at the time — having opened the Mediterranean Diving Center in Herzliya, Israel, in 1970 and expanded operations to the Red Sea in 1972 — I wanted to get in on the tourist action but faced a significant challenge: Our Red Sea dive community had yet to uncover a submerged shipwreck.

I brainstormed with a group of friends one evening about how to attract dive tourists. My dive buddy conjured up a fantasy tale of a sunken ship laden with gold coins, sent by the British to pay Lawrence of Arabia’s Bedouin fighters, who were assisting Britain’s war efforts against the Ottoman Turks in World War I. In his fantasy, the ship never made it, hitting a reef and conveniently sinking in our region.

I began sending out teasers to dive travel agents and publications, hinting that a sunken wreck with a possible cache of gold coins was in our waters. Articles about this mysterious wreck even appeared in a few major dive magazines, creating a buzz and drawing divers to Sharm El Sheikh.

The Three-Cigarette GPS

While the Lawrence of Arabia story was pure fiction, we were determined to find a wreck that might supplant our invention. Local knowledge was our best resource, and I reached out to my friend Suleiman, a Bedouin fisherman, tracker, and native historian.

When I quizzed him about possible sunken wrecks, he removed his wool cap, scratched his head, and said there might be something around Ras Muhammad in the Gulf of Suez. When I pressed him about how to find it, he said, “Take your boat around Ras Muhammad, cruise in the direction of the setting sun, smoke three cigarettes, and by the time you have finished your third smoke, you should see some waves breaking on an offshore reef. At the reefs’ southwest point, there is an excellent fishing spot, and local lore has it that a ship went down there.”

Soon afterward I was guiding a group of American divers led by Carl Roessler of See and Sea Travel, and I suggested a day of exploratory diving with the possibility of finding a wreck. They agreed, and using Suleiman’s navigation directions, we located the Sha‘ab Mahmoud offshore reef.

I can remember what ensued that day in 1977 as if it were yesterday instead of half a century ago. I suited up for a reconnaissance dive, and as soon as I hit the water, there it was. Sprawled out below me, lying upside down directly under our dive boat, was the Sinai’s first sunken shipwreck. At the time we were unaware of Jacques Cousteau diving the Thistlegorm at nearby Sha‘ab Ali reef in the early 1950s. We later learned that he wrote about it but never revealed its location; other divers began visiting it in the early 1990s.

I should note that others claimed to have previously found the wreck, but no one can know for sure who was first, as secrecy was the norm. What is certain is that our team was the first to research it and bring the Dunraven to the attention of the international dive community.

Unveiling Dunraven’s Identity

Confirming the wreck’s identity took time. We didn’t know its name or history for at least a year. The breakthrough came when a dive group explored the ship’s galley and found porcelain plates bearing the ship’s name.

Further confirmation came from a more arduous task: On a later dive our team used a pneumatic grinder to clear the coral covering the stern of the ship, revealing the name Dunraven. With that, the confirmation was certain.

Other artifacts found on the wreck, such as glass torpedo-shaped bottles for the early carbonated drink Webb’s Double Soda, provided crucial historical clues. Their manufacturing dates pushed the wreck’s timeline back to the 1870s, further debunking our Lawrence of Arabia narrative.

Bringing the Dunraven to the World

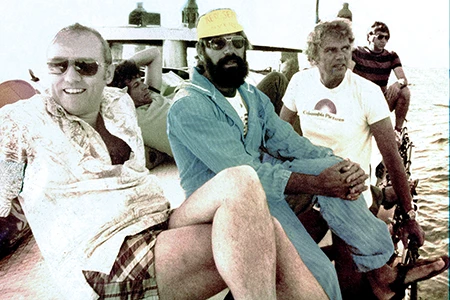

After the initial discovery, I convinced Israeli film producer Dan Arazi of Kastel Films to produce a documentary, which garnered the interest of the BBC and their prestigious documentary series The World About Us. Famed underwater cameraman Chuck Nicklin shot a half-hour film on the Dunraven titulado Mystery of the Red Sea Wreck.

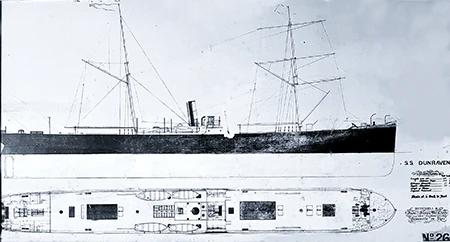

The BBC research team worked with British Admiralty records to confirm that the SS Dunraven, a British merchant ship built in Newcastle upon Tyne and launched in 1873, sank on April 22, 1876, after striking the Sha‘ab Mahmoud reef. Thankfully, no one perished in the sinking.

Perils of Diving the Wreck

Making the documentary involved many repetitive decompression dives. There were no modern dive computers at the time, so divers relied on the U.S. Navy decompression tables and bladder-type Scubapro SOS decompression meters. We had spare tanks on drop lines and strategically placed them on the sand at the wreck’s entry and exit points for diver safety.

I had a harrowing experience during a penetration dive when other divers kicked up the sandy bottom and caused me to lose sight of my backup tank. I was running critically low on air at 100 feet (30 meters), but I managed to locate the tank when I spotted tiny bubbles ascending through the silt cloud from a leaking regulator. Drawing ever harder breaths, I was able to locate and purge the second stage, insert the mouthpiece, and take the longest breath of my life. It was one of the scariest situations in my 50 years of professional diving.

Around the same time as the documentary, Skin Diver magazine sent its legendary editor and filmmaker Jack McKenney to write a Red Sea diving cover story for the February 1979 issue and shoot a promotional film called God’s Other World: The Red Sea. It was one of the first films about Red Sea diving for the American public, and it featured theDunraven. The film premiered at the DEMA Show in 1979, and these efforts led to the wreck’s instant notoriety. I also chronicled those exciting, early days of Red Sea diving in my memoir, Treasures, Shipwrecks and the Dawn of Red Sea Diving.

A Race Against Time and Changing Borders

The effort to document and explore the Dunraven became a race against time for multiple reasons beyond the typical urgency to explore a new wreck before others might pillage it. At that time in the Red Sea, a significant geopolitical factor loomed: the November 1979 peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. The Camp David Accords stipulated that Israel was to withdraw from the Sinai in phases.

On Jan. 25, 1980, the first phase of Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt divided it along a line from El Arish on the Mediterranean Sea to Ras Muhammad on the tip of the southern Sinai’s Red Sea waters. The new interim border placed the Dunraven in Egyptian waters once again, along with Sinai’s most famous dive site, Ras Muhammad. These two prime dive sites would soon be out of our reach as Israelis, at least for some time. It was only after Israel’s complete withdrawal in April 1982 that our new liveaboard operation, Fantasea Cruises, would resume dive trips to the Dunraven and other sites in the Suez Gulf.

El Dunraven rests inverted in two sections, at depths ranging from 49 to 96 feet (15 to 29 m). It offers world-class diving, and its discovery became part of a broader exploration of Red Sea wrecks. Divers can now enjoy dozens of excellent wrecks scattered throughout the Red Sea.

Explore Más

Find more about the Discovery of the Dunraven in these videos.

© Alert Diver – Q4 2025