Una bocanada de aire —nada más y nada menos.

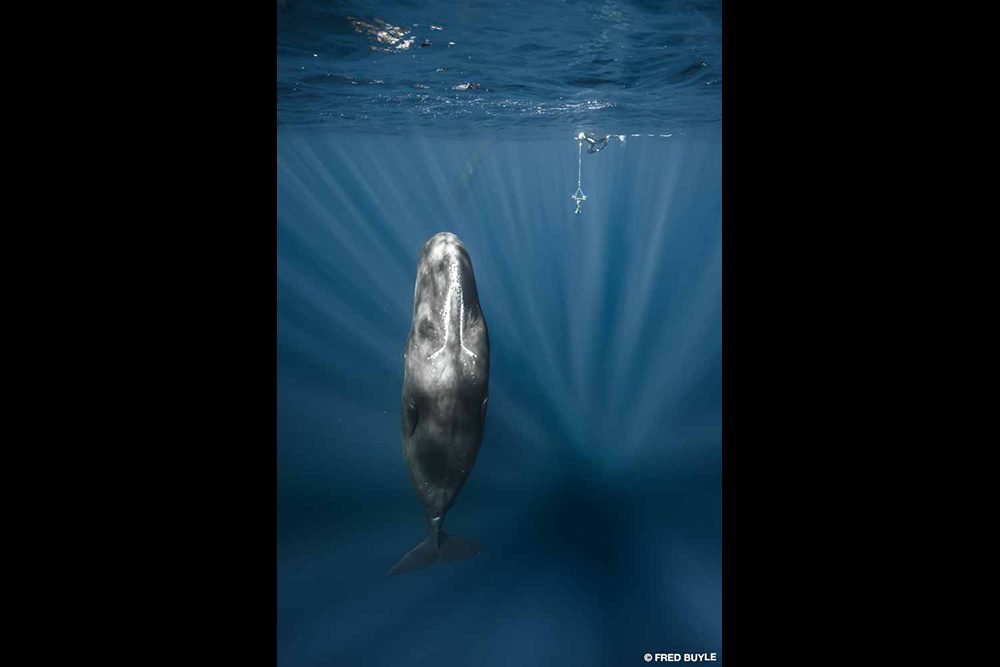

UNA DECLARACIÓN EN EL SITIO DE FRED BUYLE explica brevemente su enfoque de la fotografía submarina: “para capturar sus fotos y videos, Fred utiliza una formula simple: el agua, la luz disponible, una cámara y una bocanada de aire, nada más y nada menos”. A esa lista le agregaría un extraordinario ojo para la composición y una pasión por situarse en cualquier lugar donde haya oportunidades para tomar fotografías. Las imágenes de su book representan décadas de viajes a destinos exóticos lejos de su hogar en las Azores. Ha pagado menos cargos por exceso de equipaje que otros fotógrafos, ya que su vida y estética son extraordinariamente minimalistas para un hombre con tantos logros.

Buyle se inició en la fotografía naturalmente —algunos dirían que es algo genético. Su bisabuelo era un fotógrafo innovador y prestigioso en Bruselas y retratista de la familia real belga. Su abuelo era pintor de bellas artes y su padre fotógrafo publicitario y de moda en la década de 1960. Buyle se perdió la época activa de la vida de su padre en la fotografía de moda, ya que se había retirado de esa carrera para cuando Buyle nació.

Cada verano, durante al menos dos meses, la familia zarpaba a Dinamarca, el Reino Unido y Noruega. La navegación era una pasión familiar y, si bien sus padres no eran buzos, Buyle sentía curiosidad por todo lo relacionado con el océano. Comenzó a leer de forma voraz a los 4 años. A los 7 años satisfacía su curiosidad por el mundo submarino a través del snorkel, y comenzó a pescar con arpón unos años más tarde. Cuando tuvo que sumergirse a mayor profundidad para cazar, aprendió a compensar. Pasaba más tiempo observando que pescando con arpón, y el buceo en apnea se convirtió en parte de su vida.

Cuando era adolescente obtuvo su certificación de buceo en Bélgica y se convirtió en divemaster PADI a los 18 años y en instructor un año después. No obstante, la idea de depender de un tanque y un regulador nunca le interesó tanto como la estética de una sola respiración. El buceo en apnea se volvió un deporte más organizado en la década de 1990, y Buyle fue parte de ello. En 1995, estableció su primer récord mundial de 51 metros (167,3 pies) en la categoría de peso variable y luego continuó con el récord de peso constante de 53 metros (173,9 pies) en 1997. Superó ese récord posteriormente en 1997 a los 58 metros (190,3 pies) y en 2001 a los 65 metros (213,3 pies). En 1999 superó la barrera más difícil del buceo en apnea, los 100 metros (328 pies), lo que lo convirtió en la octava persona en hacerlo oficialmente.

Para el año 2000 claramente se había establecido como parte de la realeza del buceo en apnea, pero ¿cuándo comenzó con la fotografía submarina?

Para el año 2002 me había aburrido de la práctica de buceo en apnea para romper récords, pero quería memorias de lo que veía bajo el agua. Más o menos en esa época, las revistas comenzaron a interesarse en las competencias de buceo en apnea, así que fotografiar a buzos en apnea fue una transición natural para mí. Los buzos en apnea de elite eran una comunidad pequeña, y nuestra confianza era recíproca. Tenía las habilidades necesarias para descender a una profundidad suficiente para tomar una foto dramática, sin embargo, sabía lo suficiente sobre la cultura como para hacerme a un lado y no interferir con el buceo. No se le puede pedir al modelo una toma más durante una competencia internacional, así que aprendí a hacerlo bien la primera vez.

Tomé mis primeras fotos submarinas digitales en 2001, por lo que, si usted comenzó a fotografiar en 2002, supongo que nunca fotografió con película.

Es cierto. Comencé con la fotografía submarina con una cámara digital Nikon Coolpix. Los archivos digitales no eran tan malos, pero el retardo de obturación era horrible. Debías presionar el botón de liberación del obturador y anticipar dónde estaría el sujeto cuando la cámara capturara la imagen. Cambié a cámaras digitales Canon para obtener archivos de mejor calidad, más opciones de objetivos y un mejor obturador. Las cámaras continuaron mejorando entre todos los fabricantes, y para el año 2016 había vuelto a cambiar a Nikon y eventualmente me convertí en uno de sus embajadores. Había estado fotografiando con una Nikon D810 pero me actualicé a una Nikon Z 7II en un esfuerzo por tener una menor ocupación de espacio y una posición más hidrodinámica en el agua.

Su estilo actual parece estar orientado a los animales grandes, a menudo con buzos en apnea, pero con un énfasis en la carismática megafauna marina.

Siempre me ha gustado estar con animales grandes, pero el buceo en apnea es en gran medida un deporte en equipo. Todos conocemos los riesgos de desvanecerse en aguas superficiales, por lo que viajamos y buceamos juntos. Es importante ser un buen ejemplo en cuanto a la seguridad, e incluso hoy en día puedo llegar a descender a 61 metros (200 pies) para aprovechar una oportunidad de tomar fotografías, por lo que confiamos en la seguridad que tenemos al cuidarnos unos a otros. Siempre tenemos protocolos de seguridad, incluso si realizamos un buceo relativamente superficial para fotografiar cachalotes durmiendo. Debido a que siempre hay uno o dos de nosotros en el agua, puedo ubicar a un buzo en apnea cerca de la vida marina. Eso proporciona una escala y un interés humano, y mis compañeros quieren estar junto a grandes criaturas de todos modos. Tengo el beneficio de estar allí para capturar la imagen.

La diversidad del tema elegido —tiburones blancos, tiburones tigre, mantas, tiburones ballena, cachalotes e incluso belugas— da una idea de su compromiso a nivel geográfico. Debido a que puede viajar con poco equipaje sin luces estroboscópicas ni equipo de buceo, ¿cree que eso contribuye a un enfoque minimalista?

Esa es mi manera de viajar y mi manera de vivir. Soy muy minimalista. Vivo en las Azores para poder estar cerca del mar. Cuando las condiciones son correctas, puedo tomar mi cámara, subir a una embarcación rápidamente y encontrarme en el agua con tiburones azules, rayas mobula o lo que sea que haya allí. Nunca sabes qué tipo de encuentro puedes tener, e interactuar con todo eso es la gran alegría de mi vida. Pero mis viajes no son al azar. Tengo una idea de qué quiero fotografiar y dónde ir para tener éxito.

En 2007, por ejemplo, quería capturar algunas imágenes de tiburones blancos en agua cristalina. Mark Addison había tenido suerte buceando en apnea con tiburones en el océano Índico cerca de la costa este de Sudáfrica. Había descubierto que, si esperábamos la llegada agua cálida y cristalina sobre los pináculos, podríamos encontrar tiburones blancos. Nadar sin jaulas era inusual en ese entonces, pero Mark lo había hecho muchas veces y me ayudó a darme cuenta de que era posible. Resultó ser una experiencia mágica que mejoró considerablemente mis conocimientos sobre el comportamiento de los tiburones. Ese año mis fotos de buzos en apnea nadando tranquilamente junto a enormes tiburones tigre en Sudáfrica fueron ampliamente distribuidas y se volvieron mis primeras imágenes virales.

Gran parte del resto de mi trabajo en círculos de conservación tuvo lugar porque los buzos en apnea pueden hacer cosas que son imposibles en el buceo con tanques o rebreathers (recirculadores) porque son demasiado molestos e intimidantes para los animales. Colocamos marcas acústicas para hacer un seguimiento de la migración a tiburones martillo en Rangiroa, Tahití, a lo largo del Corredor del Pacífico Oriental (las Galápagos, Cocos y Malpelo) y a tiburones blancos cerca de la Isla Guadalupe en México. Nuestra presencia discreta nos convirtió en valiosos asistentes submarinos de los investigadores de tiburones.

Su cámara principal es la Nikon Z 7II sin espejo, que ofrece menos resistencia al agua. ¿Cree que esa característica es importante?

La evolución de mi equipo siempre es por tamaño y eficacia. Cuando viajo tengo una pieza de equipaje que registro con mi ropa, aletas, máscara, snorkel y traje de neopreno. En mi equipaje de mano llevo una cámara y una caja estanca, un cuerpo de cámara de repuesto y dos o tres objetivos. No necesito luces estroboscópicas ni lentes macro. Siempre trabajo con objetivos gran angular, luz disponible y una bocanada de aire.

Hablando de eso, ¿tiene que entrenar constantemente para mantener el máximo nivel de eficacia en el buceo en apnea?

He entrenado para la práctica de buceo en apnea desde el año 2004, cuando dejé de competir. Lo importante es tener un estilo de vida saludable. Nado con bastante frecuencia, ando en bicicleta y presto atención a lo que como. El estiramiento me ayuda mucho, y tengo una máquina de remo para cuando el clima es malo. Honestamente, prefiero trabajar en mi jardín o disfrutar de una agradable caminata todos los días. Me siento afortunado por aún poder llevar a cabo el trabajo que deseo hacer, y espero con ansias la próxima gran aventura.

Vea más del trabajo de Buyle en nektos.net.

Explore Más

Vea más del trabajo de Fred Buyle en una galería de fotos complementaria y en los videos a continuación.