Over the years I have often admired Gerald Nowak’s underwater photos. There is so little overlap between the markets available to European versus North American photographers, however, that I did not know the backstory of his career. A recent phone call rectified that.

I discovered that personal strategies for leveraging marine photography into a lifestyle might be similar, but the magazines and clients tend to differ. It is strange that photography markets are not more homogenized in this age of digital image transmission and the ubiquitous internet. Nowak has successfully navigated this disjointed environment for the past three decades.

Jacques Cousteau or a fantasy of underwater exploration often defined the early passion of many underwater photographers. But for Nowak it was not being quite good enough as a soccer player. That sport was his first love, but by the time he was 14 he knew he needed to find a new sport in which he could truly excel. He shifted from the terrestrial to the aquatic, becoming a rescue swimmer — a variant of what we call a lifeguard.

The small riverside Bavarian village where he lived was idyllic in many ways. There were enough accidents on the river, however, that they needed rescue swimmers. In a twist of fate, one of his water-rescue instructors was Stefan Michl, now an executive with Mares, who at the time was a dive instructor from the neighboring village. You might say something in the water there set both of them on their dive industry trajectories, which brought them together again later in life when Mares sponsored Nowak.

By age 20 Nowak was ready to try something new beyond the small-town life. He moved to the city and became a dental technician in a lab his father owned. The next chapter of his life, however, drew him closer to his eventual career.

Travel began calling to him, so at 25 he became a flight attendant for the German airline LTU Süd. Aviation was intriguing enough that he got his pilot’s license, but he eventually bristled at the airline’s control over his schedule. Those years took him to dive destinations such as Thailand and the Maldives. By age 29 he had quit the airline to take a trip around the world.

Nowak had been taking photos to document all his travels, so it wasn’t a massive leap to try underwater photography, although his early gear was fairly rudimentary. He had a Sea & Sea Motormarine II — an amphibious film camera — but with only the standard lens and a macro accessory. While diving in the Maldives, he found a wide-angle wet lens for the Motormarine on the seafloor to complete his system. He lost the wet lens on a dive only a year later, but it was time for an equipment upgrade anyway, so he got a Nikon single-lens reflex camera in a Hugyfot housing.

His next film-era equipment acquisition was the Nikonos RS. He eventually owned four of them but flooded three. By the time digital photography came around, he had started using Subal housings during his progression from a Nikon D200 to the D300, D700, and finally a D800. He has been fully immersed in the Seacam line of underwater housings and strobes since 2015 and now shoots with a Nikon D850.

Travel remained a fundamental aspect of his life, and he became an expedition leader for the tour company Schöner Tauchen. Being on the road, leading travel, and taking underwater photos led him to supply photos for dive publications. By 1994 he had published his first article, one about the Cook Islands, in the German dive magazine Tauchen. Other European dive publications followed, including Aquanaut, Unterwasser, Silent World, DiveMaster, et Sporttaucher.

Six years later Nowak was contributing images to big stock photography agencies such as Getty Images. With the industry rife with mergers and acquisitions, he once participated in a network of 150 worldwide stock agencies.

Perhaps the most significant milestone in his life and career happened in 1996 at the Boot Düsseldorf watersports trade fair. “I met my wife, Sibylle Gerlinger, at the Schöner Tauchen booth,” Nowak explained. “A year later I met her at the fair again. Soon after, we started living and working together — she as a journalist and I as a photographer.”

Nowak and Gerlinger became a perfect team. They freelanced together for Unterwasser starting in 2000 and added more work as the years went on, contributing to German dive magazines and various travel and outdoor publications (Nowak is also a whitewater kayak instructor and travel photographer). They published three to five magazine articles a month at their busiest.

They still work together but have slowed their pace. The couple and their daughter live in a little village called Landsberied, which is west of Munich, Germany, and has “more cows and horses than humans.” Nowak also works as a freelancer for the Austrian dive tour operator Waterworld Tauchreisen. He does seven or eight big photo tours a year but enjoys returning home to the quiet little village.

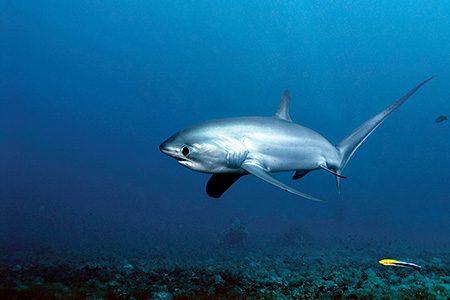

Something that differentiates Nowak’s work is his love for extremes, whether technical, cave, or coldwater diving. He is a dive instructor certified by Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques (CMAS) and Scuba Schools International (SSI) in both rebreather and trimix and has made almost 6,600 dives.

Nowak is especially committed to coldwater environments. “The tropics have been photographed 10,000 times,” he said. “It is easy and comfortable there.” He is also drawn to places such as South Georgia’s kelp forest, where he has had several great encounters with leopard seals, penguins, and other animals.

He also finds Russia extraordinary — very few people dive in the White Sea far to the north and experience its vivid winter colors under the thick ice cover. He sometimes ventures under the 3-foot-thick (1 meter) ice in Lake Baikal, far to the east and in the middle of Siberia. Lake Baikal is 395 miles (636 kilometers) long, with a maximum depth of 5,387 feet (1,642 meters), making it the world’s deepest lake and the world’s largest freshwater lake by volume, with almost 23 percent of the world’s fresh surface water. “The atmosphere under and above the water is extremely calm because few people live there,” he said, “and you won’t meet anyone underwater except your dive buddy.”

Nowak effused about his love of diving in cold water: “I have no problem if the equipment is thick and heavy. As long as I can still hold my camera, I’m happy. The main thing is that I can experience my passion: diving.”

© Alert Diver — Q1 2024