Conservation et collaboration avec un appareil photo

LES LECTEURS CONNAÎTRONT LA SIGNATURE “David Doubilet and Jennifer Hayes” from scores of National Geographic des reportages dans les magazines. Travaillant en équipe, ils ont photographié l'océan sauvage, des tropiques aux deux régions polaires, en passant par des domaines aquatiques plutôt inhabituels. Dans les coulisses, Hayes décrit avec humour leur partenariat comme une collaboration très improbable. Acres verts couple.

Doubilet grew up in a home in New York City, and Hayes came from a family of dairy farmers living on 1,500 acres at the edge of Lake Ontario in upstate New York. Her early life related to their Holstein dairy, yet her rural background didn’t prevent her from developing a crush on Marlin Perkins from his Royaume sauvage series. Inspired by his treks through nature, Hayes rode horses to explore local creeks and ponds, in her words “looking and collecting and doing.”

Meanwhile, her parents were more pragmatic. Their veterinarian bills were enormous, so they thought it would be great if at least one of their five kids became a vet. Hayes seemingly oriented to that idea, choosing to attend junior college during her senior year of high school to get started in science. There she met a biology professor who “kicked down some barriers in my mind,” she said.

Hayes embraced science and went on to receive a bachelor’s degree in biology from the State University of New York (SUNY) at Potsdam. She dutifully rode with a large-animal vet, took the Graduation Record Examination (GRE), and applied to Cornell University. She chose instead to pursue a master’s degree in zoology at the University of Maryland, where she entered as Eugenie Clark’s last graduate student. Her research under Clark focused on shark fisheries in the northwest Atlantic, which kept her at sea off the East Coast documenting shark landings.

Clark, known as “the shark lady,” was an ichthyologist of great renown, founder of Mote Marine Laboratory (originally known as Cape Haze), and instrumental in conceptualizing scuba diving as a tool for marine research. Diminutive in height, she was a giant of charisma and an influencer before the word was mainstream. She inspired Hayes to weigh practical pathways against the impractical but rewarding paths in the study of primitive fishes.

Mme Hayes est entrée dans le monde de l'entreprise à Washington, D.C., en tant que biologiste chargée d'étudier l'impact sur la baie de Chesapeake. Elle a progressé dans son travail, formé une équipe solide, gagné un salaire mirobolant avec de généreuses vacances et a acquis 100 % de ses droits dans son plan 401(k). Cependant, sa proximité avec la baie de Chesapeake lui donnait envie de se retrouver sous l'eau pour étudier le comportement des poissons.

Après ses heures de travail, elle rédige une proposition de recherche sur les esturgeons et obtient un financement de la part de la New York Power Authority. Elle a démissionné de son poste à Washington et a transféré le financement au SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry pour sa recherche doctorale sur la télémétrie de l'esturgeon jaune et la dynamique de la population sur le fleuve Saint-Laurent.

To her colleagues’ surprise, Hayes chose an $8,000 per year stipend, a tin jon boat equipped with nets, and a golden retriever over a comfortable salary and never looked back. Clark had been right: Follow your heart, not the 401(k).

Je vois que tous les chemins mènent au poisson, qu'il soit d'eau douce ou d'eau de mer, mais comment la photographie est-elle devenue partie intégrante de votre vie ?

Comme beaucoup d'entre nous ici, la science a conduit à la narration. La recherche a donné lieu à des présentations internationales de données de terrain à des collègues et à des parties prenantes. En tant que biologiste de la pêche, j'ai présenté des graphiques et des statistiques pour décrire le comportement de cet ancien poisson géant. J'ai décrit la magie dont j'ai été témoin sous l'eau, en essayant de peindre une image mentale pour un public engagé qui est une petite tribu très dévouée où nous apprenons les uns des autres.

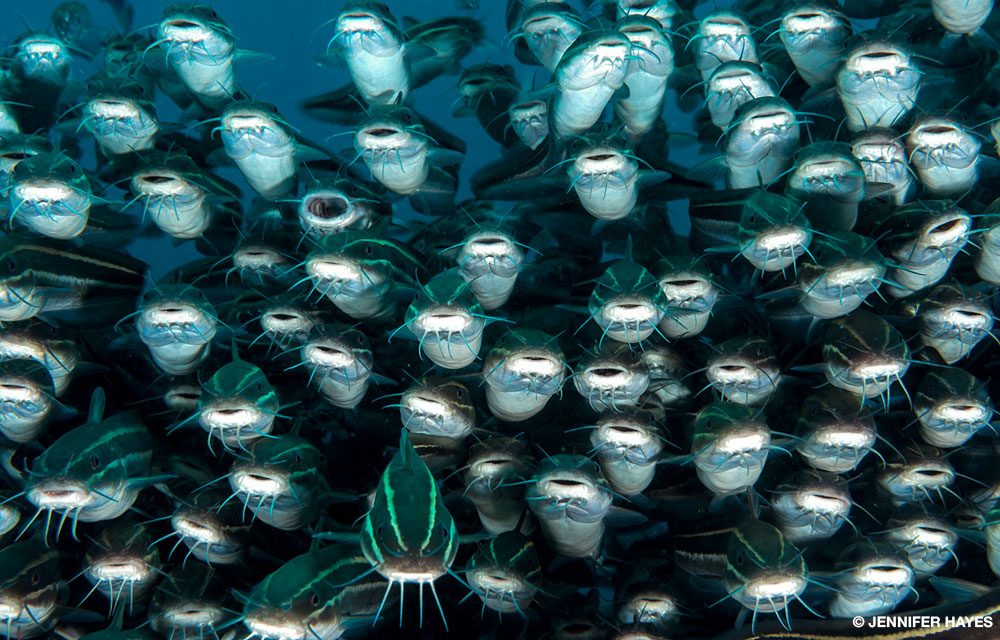

Les collègues avaient de nombreuses questions à poser : Une femelle peut-elle frayer à la fois avec plusieurs mâles ? Les mâles restent-ils ? Les poissons mangent-ils leurs propres œufs ? Préfèrent-ils un certain substrat ? Les esturgeons sont timides et rarement accessibles, mais j'avais une fenêtre, ce qui signifiait qu'il fallait sérieusement commencer à les documenter. La photographie sous-marine est rapidement devenue un outil de recherche important.

Comment avez-vous appris la photographie sous-marine ? Photographier l'esturgeon dans les eaux troubles du Saint-Laurent semble être une espèce cible difficile, d'un point de vue photographique.

Truthfully, the greatest challenge was the limited time I had with them. There’s a maximum of one week each June when they migrate to the spawning areas where they congregate, are pumped on hormones, and ignore your presence or maybe even try to spawn with you. I splurged on an underwater housing with a wide-angle lens and, rather stupidly, a costly glass dome with strobes and the requisite Nikonos V (with a fisheye lens) draped around my neck for an extra 36 frames.

J'ai suivi une courbe d'apprentissage abrupte avec des inondations, des dômes outrageusement rayés et des cadres sous-exposés. Les anciens sont apparus et j'ai créé des images d'esturgeons faisant des choses secrètes. Les subventions fédérales, nationales et privées sont arrivées plus rapidement lorsque les bailleurs de fonds ont réalisé qu'ils pouvaient documenter visuellement leur investissement dans la conservation de cette espèce menacée.

J'ai rapidement appris que les images ont un pouvoir et qu'elles valent bien plus que 1 000 mots ou données. Les photographies ont donné lieu à des articles dans des publications sur la conservation, NPR, le New York Timesdes revues à comité de lecture et des contributions à des ouvrages.

Vous avez quitté l'eau douce pour la mer, un partenariat, et National Geographic?

David et moi nous sommes rencontrés il y a mille ans sous l'eau à Bimini, aux Bahamas, où je travaillais sur les requins citron avec feu Sonny Gruber de l'université de Miami. Pour capturer les femelles gravides, j'ai installé des blocs et des stations d'appât lestées dans les eaux peu profondes, dans le but de repérer les lieux où les requins mettent bas.

I was underwater assessing a female when someone submerged with a fancy camera and began taking pictures. That somebody was David Doubilet, who was there to document Gruber’s program. We brought the female to the surface, quickly attached her transmitter, and released her. She swam for the shallows and began birthing her pups. David had what he came for: the first birth of a shark. Our team had what we came for: more proof that lemon sharks drop their pups near the protective cover of mangroves.

Par la suite, nous nous sommes croisés dans des laboratoires marins, sur le terrain et dans des centres de recherche. National Geographic over many years as I assisted on various grant projects. A Doubilet–Hayes partnership formed, where I would submit images, and selects got published, but it was rightfully a David Doubilet vision and byline in those days. Eventually, editors suggested a shared byline.

Aujourd'hui, David ou moi pouvons proposer une mission en fonction de nos intérêts, qui peuvent être très différents. Je suis actuellement en train de documenter deux histoires de longue durée pour le compte de National GeographicLe changement climatique : un regard global sur l'esturgeon et le phoque du Groenland.

No matter where the inspiration originates, we generally approach these assignments as a team — unless it involves a snowmobile, snowshoes, skis, or a horse, and then it is all mine.

Avec deux photographes aussi talentueux sur une même mission, y a-t-il une compétition pour les photos ? Ou bien comptez-vous qui obtient le plus de photos dans l'article final ?

There is zero competition. The story is far more important than the credit — his, mine, or other contributors. Every single click of the shutter is a team collaboration that includes the people who fill the tank, drive the boat, or guide you to a subject. Land in a different country and see how far you get without priceless support. The best part of any assignment is submitting an assistant’s work along with our own — or better yet, discovering a body of work out there and getting their coverage in front of the right editor.

National Geographic Partners nous a permis de collaborer à de nombreuses histoires, à des projets de livres, à Lindblad Expeditions et à des tournées de conférences Nat Geo Live. Nous participons également à des projets commerciaux et personnels, les collaborations dans le domaine de la conservation étant prioritaires.

It has been a privilege to support the Ocean Geographic Elysium Expeditions in Antarctica, the Arctic, the Coral Triangle, and most recently the Antarctic Climate Expedition in February 2023. A team of established and emerging photographers, videographers, scientists, musicians, writers, and artists create a body of work that includes a book, film, and an exhibition that goes on tour where it will have the most impact — not museums or out of the way art galleries, but major shopping malls in places such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Chendou, China, where young people come to buy the next new thing. These projects are well worth the investment. The best part is working with old friends and making new ones.

We’re friends on social media as well as in real life, and I’ve noticed some of your most highly trafficked posts are videos. Do you find yourself moving more in that direction?

Moving or moved? We have a clear mandate now: Don’t come back without the video. Video is probably half of what I do. Not surprisingly, I am the designated videographer among us. I’ll use whatever it takes — GoPro, drone, dedicated iPhone, or digital camera.

Disney est désormais propriétaire de National Geographic Partners. Pensez à tous les canaux qui s'offrent à vous pour intégrer la vidéo dans vos projets : Programmation spécifique à Disney, TikTok, Instagram, filiales d'ABC, productions YouTube, tournées de conférences et National Geographic Expeditions. La demande s'ajoute à une discipline que nous devons prendre au sérieux.

L'avantage, c'est que j'aime ça. L'inconvénient, c'est de passer de l'image fixe au numérique. Quel que soit le format dans lequel je tourne, je pense que je devrais être dans l'autre. Je ne peux qu'espérer que si je l'ai en vidéo, David l'a en photo.

Que nous réserve l'avenir ?

We’re directing our efforts on conservation, collaborations, and the next generation of ocean advocates. We are specifically interested in giving voice, space, and place to emerging talent by getting them on our shoulders to reach higher — or deeper in our case. We are stalking scientists and their work toward solutions in the sea and bringing their stories out of peered-reviewed papers and into the public eye.

Nous étions à Raja Ampat, en Indonésie, en janvier 2023, pour ReShark, une nouvelle solution simple pour la conservation des requins : Remettre les requins dans la mer. Mark Erdmann, de Conservation International, a vu une opportunité lorsqu'il a appris que les aquariums abritant des requins zèbres avaient des excédents d'œufs de requins zèbres. Sachant que les zones marines protégées de Raja Ampat abritaient des populations de requins zèbres, il a eu une idée. Aujourd'hui, ReShark représente plus de 70 parties prenantes qui déplacent les œufs vers des nurseries de requins en Indonésie, où des scientifiques marins locaux les élèvent et les relâchent.

These stories are valuable because they allow us to share hard truths about loss, provide solutions, and document conservation successes that may inspire others to innovate. You can’t beat up people and send them off with only doom and gloom.

Our job now is to prioritize projects with impact. David will focus heavily on the Oceans Through the Lens of Time project, and I will head to the Canadian Arctic on snowmobile with scuba tanks. In the meantime we will connect with other storytellers to document the most important story on Earth: Earth Itself. Keep shooting, and come find us underwater. Let’s collaborate! AD

EN SAVOIR PLUS

En savoir plus sur Jennifer Hayes et voir d'autres de ses travaux dans une galerie bonus et ces vidéos.

© Alert Diver - Q3 2023