SOMETIMES A SINGLE CLICK OF THE SHUTTER release can change a career trajectory. That’s what happened in 2014 after Matthew “Matty” Smith won a category in the London Natural History Museum’s prestigious Wildlife Photographer of the Year Award. He was aware of the stinging cnidarians known as bluebottles (Physalia utriculus)from a lifetime of surfing. Colonies of them sweep along Sydney, Australia’s beaches in summer. Matty had the idea of photographing them using a close-focus, wide-angle technique. They aren’t very large — the floats rarely get larger than 6 inches — so to make it appear impressive in the photo, he had to work very close and use perspective distortion to his advantage. Because the long tentacles dangling underwater are critical to the illustration, his idea was to shoot an over/under using a dome port on a camera housing to capture the above and below in a single frame.

His masterful photo was taken at dawn with the sun just breaking the horizon, a gorgeous blend of strobe and ambient light. A portfolio of significant marine images with that as the lead was the beginning of what he calls his “lucky streak through hard work.” In 2014 he won the Australia Geographic Nature Photographer of the Year Award and swept first, second, and third places in the Ocean Geographic Pictures of the Year awards. Because of his successes in various competitions, he got an email from Nikon Australia offering him the coveted ambassador role, and Aquatica camera housings agreed to sponsor him. He met Michael Aw of Ocean Geographic through their photo contest. Later that year he traveled with Aw’s group to Cuba’s Jardines de la Reina, where he expanded his over/under portfolio with shots of the resident saltwater crocodiles.

While 2014 was a transitional year for Matty, his life had been moving in this direction for decades. Raised in central England, he wasn’t next door to the sea, but the country is small enough that weekends at the beach with his parents were possible. As they understood how passionately Matty was attracted to the sea, his parents would more frequently pack his inflatable surfboard and go, sometimes venturing on family holidays to the southwest coast of France or the Spanish seashore. In 1999 he left England for Australia and began his endless summer.

What was your inspiration for leaving home to move to the other side of the world?

I decided to go to Australia at 23 years old and be a backpacker for a year. The infrastructure is great for young people who don’t have much money but want to travel around and have a grand adventure. I was a skilled welder and could find work as I needed it, so I’d move from place to place around the Australian coast, work to save up some money, and then go off to the next place. I made a lot of interesting friends and saw so much of the beautiful country, which was much different from what I’d known living in the U.K.

Were you doing photography at that time?

Absolutely. I was always drawn to photography, but I had never pointed my lens at much beyond the sea. I had a Nikon FM2n film camera and a Liquid Eye surf housing with a trigger on the handle on the housing’s bottom. All I had in mind was to surf and take pictures of other surfers. Photographing surfers in the tube was me trying to emulate surf photographer Tim McKenna, my idol at the time. I knew the physics of photography by then and even had a darkroom back home in the U.K. Getting surf images with a telephoto from the shore and in the ocean with my housing was my passion.

INCOMING

I wanted to shoot a split waterline image of a great white shark, and on this day at the Neptune Islands in South Australia, I got my chance. The wind had dropped off, and in the evening the ocean was glass. I needed a calm shark to avoid risk to myself or the animal while pulling off this image. This shark circled near the boat’s stern for half an hour. It displayed relaxed body language, so I attempted the shot. Shortly after placing my pole-mounted camera in the water, the shark showed some interest and cautiously approached. I quickly fired a sequence of frames before safely pulling the camera out of the shark’s way.

HIGH FIVE

I shot this image at Lissenung Island, Papua New Guinea, a few years ago for the island dive resort’s turtle rescue charity. We knew a hawksbill nest was due to hatch soon, and I’d have a window of just minutes to nail this shot of a hatchling. I spent several hours practicing different dome, lens, and lighting setups on a small piece of driftwood, so I knew I would be ready when the opportunity arose.

SMILING ASSASSIN

It’s not often you remember the exact moment you push the shutter button, but I remember every detail of this frame — the sweat beading on my forehead, trying not to move too much as I balanced my huge dome port, and mumbling to myself about not messing this up. It was during my first trip to Cuba with Michael Aw and Ocean Geographic, and it was my first time being in the water with a saltwater crocodile. The experience was sobering yet forever memorable.

The darkroom experience is kind of unusual. I often meet prominent photographers who have made only digital images and never used film.

The quiet darkroom, with only the safelight’s soft illumination and the Dektol tray’s gentle sloshing as I rocked it back and forth, watching the image materialize, was magical. I loved seeing the surf images in my mind’s eye, getting the chromes back, and fulfilling that vision in my home darkroom. After a year of traveling around Australia, living self-sufficiently, and shooting, my visa expired, and I had to return to England.

That was hard for me. I had grown used to the tropics, and surfing in the 43°F water was intimidating. But I had to get back in the sea. I put on my heavy winter wetsuit and paddled out for the first wave. As soon as I did my duck dive, the zipper perished. I had gone from board shorts to a leaky wetsuit in frigid water in just a week.

I slogged through the next four years like that, working as a draftsman for an engineering firm and doing whatever I could to get back in the ocean. Engineering paid the bills, but I knew I needed warm, clear water in my life. The company I worked for had a contract in Australia, and I managed to get myself assigned there, based at Airlie Beach on Queensland’s central coast. I was now based along the southern Great Barrier Reef, and life was good!

FAMILY PORTRAIT

People often say that pinnipeds are the puppy dogs of the ocean. None fit that description more than the Australian sea lion. Catch one in a good mood, and I’m sure this wild animal would fetch a ball for you. They often get excited when swimmers are in the water and will zoom about at lightning speed. To catch one of them looking more relaxed, I had to wait until all the other swimmers had exited and try to project calmness to the sea lions with my body language. Sure enough, it worked, and they soon settled into this wonderful family portrait.

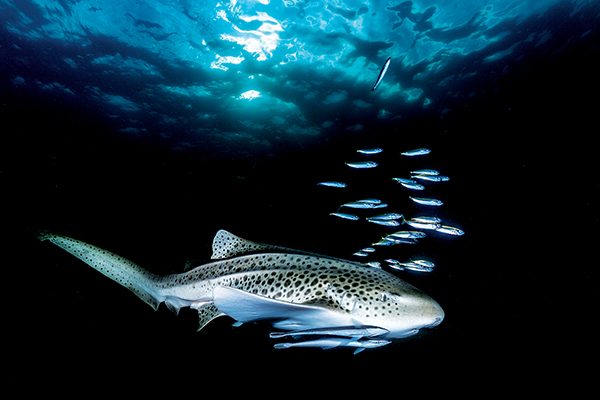

ENTOURAGE

Julian Rocks is off Byron Bay, the easterly point of Australia’s mainland. Once a year it hosts a massive aggregation of leopard sharks (known in the U.S. as zebra sharks). Every year from February to April, hundreds of them occupy a few small dive sites around the rocks — it’s an underwater photographer’s dream. This shot was after a tremendous day of diving. The sun was low in the sky, and the water was getting dark. I was heading back to the boat, but I couldn’t resist chasing this one last frame as the entourage passed.

You started as a topside photographer with a surf housing but now were somewhere with more diving than surfing. How did you start diving and capture your first underwater photos?

There wasn’t much surfing, but there were lots of dive shops, so I decided to try diving. I fell in love with it right away, and everything I saw along the Great Barrier Reef left me in awe, so taking a camera underwater inevitably followed. I had a Nikon F80 (N80 in the U.S., a film camera), so I bought an Ikelite housing and DS50 strobe. When it was time to migrate to digital, I went with a Nikon D300. By 2013 I had the idea for that bluebottle over/under, but it took me a full year of experimenting to learn what time of day to shoot, how to balance the strobes, and how to get close enough with my wide-angle lens and dome port to make it seem large. Most bluebottles are smaller than my thumb, so it was a tricky task. I was shooting a Nikon D810 in an Aquatica housing with a 14-24mm lens as my primary tool for wide-angle when I went to Cuba with Michael Aw.

When I noticed your photographs in prestigious publications, I also saw underwater photo enthusiasts talking online about “Matty’s dome.” I know you make 12-, 17-, and 18-inch-diameter acrylic dome ports with mounts to most popular aluminum housings. Your early photo hero, Tim McKenna, endorsing your dome port on your website is a full-circle moment. That must be exciting for you.

It is, and my domes have created lasting friendships with many of the big names in underwater photography. I’m an obsessive person, and I wanted a really good depth of field in my over/unders, from the sand in the foreground to the sun kissing the horizon. I couldn’t do that with a 9-inch dome port, even with a fisheye lens at f/22, so I went to the 12-inch diameter port and was instantly amazed. The corners were much sharper at any aperture. If 12 inches was good, I thought 18 would be even better. While it is optically amazing, it ends up being a specialty tool, as it is hard to travel with and creates a lot of buoyancy that we have to counteract with weights.

INKED

The annual giant cuttlefish aggregation is a wonderful and unique event in South Australia. From May to August an estimated 250,000 cuttlefish gather around Point Lowly off the small industrial town of Whyalla to fight and breed. It’s a spectacle that every diver should experience at least once. Moments before this frame, I had observed three large males trying to court a single female. As I approached, a fight broke out between two males, and they inked the water as they furiously grappled each other. Their fight rolled out of frame, the female bolted, and this one male was left in the aftermath, still displaying his vivid courting colors.

BALLED ANEMONE

I can’t go past an anemone fish without squeezing off a few shots. When it’s a purple, balled-up anemone with clownfish, that’s worth a few minutes of any dive. I shot this for an article I was writing for PNG Air’s inflight magazine, and it was a few minutes into my first dive of the day. The magical thing about spotting balled-up anemones at depth is that you never know what color they’ll bless you with until you preview your first frame. Sometimes it’s red, orange, or green, but I was ecstatic when I saw this shade of purple on my camera screen.

Is your career all photography all the time these days?

I’m still torn between two worlds — a partnership in a small engineering firm in Wollongong, New South Wales, and my underwater photography. Lately, I have also been offering workshops in advanced underwater photography and have organized photo tours to places such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. I try new techniques to avoid boredom, but the best thing is sharing some bit of knowledge with a student and seeing them win an award or noticing one of their photos in dive media.

Do you have a particular technique you’re currently obsessing over?

I’ve been working with a polecam of my own design that integrates the Aquatica monitor for external viewing. I just had fantastic luck with one of my great white shark shots taken with Andrew Fox in South Australia. I combined my 12-inch dome and polecam to capture the shark coming up to the marlin board (swim platform). Like my bluebottle shot, this one was a successful prize winner, taking home the title of British Underwater Photographer of the Year in the prestigious Underwater Photographer of the Year contest. I like to think that ingenuity and engineering can combine with skill and a little bit of luck to create an image that no one has ever seen before.

BLUE-RINGED OCTOPUS

The southern blue-ringed octopus is a potent and possibly deadly little creature. I love night diving for these guys at my local harbor in Wollongong. Onlookers always give me strange looks as I’m gearing up to get in at this mid-city spot on cold winter nights. It’s not really a dive spot. You wouldn’t go there during the day, as it’s only about 10 feet deep, dirty, and filled with sailboat traffic. But come nightfall, treasures emerge, and the excitement never gets old when I spot one of these doing its midnight rounds.

LERU CUT

No dive trip to the Solomon Islands is complete without a trip to Leru Cut. It consistently has the clearest water I have ever seen, and the light is to die for. My wife, Lauren, and I have dived this spot many times, but we wanted to shoot something a little tricky and different this time. We wanted to portray a sense of otherworldly exploration. It’s quite dark in the cut, so to get a low noise, low ISO shot, I set the camera on a tripod for a long exposure, and Lauren had to remain very still. She did a great job touching down on the sand without disturbing a single grain, which made me look like a pretty good photographer.

TWIN TUNNELS

I framed my wife, Lauren Thomas, descending into the Twin Tunnel dive site in the Solomon Islands. It’s a seamount where you can dive down one of the two vertical lava tubes of an extinct volcano. You exit into the open ocean at around 115 feet through a short cave in the side of the mount. This dive site has to be one of my favorite dives in the Solomons. I had envisaged this image since first diving the spot a few years previously, so Lauren and I planned this frame before we hit the water. Lauren is a legend and pulled it off perfectly on the first go.

OURS

Near Sydney is a recurring wave that is ranked by many as one of the top five most dangerous waves to ride in the world. It’s named Ours by the few local guys crazy enough to paddle into it. It breaks over a shallow sandstone ledge just yards away from a dry rock shelf, so if you fall, there is nowhere to go. It’s an intimidating place to swim with a camera. It’s loud, there’s a lot of current, and anything could be swimming beneath you in the deep drop-off. The surfer is Evan Faulks, one of the masters of taming this wave. I remember our connection in this shot, with him staring out of the wave barrel straight into the lens barrel with intense concentration. I knew it was a keeper. Before marine wildlife, surf photography was my forte, and I still greatly respect those who excel in this field.

EN SAVOIR PLUS

Découvrez Saba dans cette vidéo et dans une galerie de photos.

© Alert Diver - Q3 2022