Imagine ver un naufragio en su totalidad, con todos los artefactos en su lugar y exactamente como yace en el fondo. Ahora imagine hacer eso desde casa antes de bucear y compartir su punto de buceo favorito con amigos que no son buzos o incluso permitirles realizar un buceo virtual. Todo esto es posible a través de la fotogrametría.

La fotogrametría es el proceso que supone capturar una serie de fotografías o videos de un objeto, como un naufragio, y luego cargar esas imágenes en un software que puede triangular los puntos fotografiados para crear un modelo 3D. Esta tecnología puede usarse para muchas aplicaciones del mundo real, lo que incluye arquitectura, ingeniería, investigación forense, arqueología, cartografía y videojuegos. Disfruto de ver cómo los naufragios cobran vida de una manera que una sola foto nunca podría lograr.

Me gusta utilizar esta tecnología y esforzarme para experimentar y probar nuevas técnicas bajo el agua. La fotogrametría era algo que había querido aprender durante años. En abril de 2020, comencé a aprender a escanear objetos y usar el software Agisoft Metashape con la orientación de mi gran amigo Marcus Blatchford. Comencé escaneando objetos en mi casa con solo 15 a 50 imágenes para aprender a usar el software y los procedimientos fotográficos en tierra antes de intentar capturar sujetos bajo el agua.

A continuación, fui a una cantera para probar mis nuevas habilidades y experimentar con diferentes técnicas de iluminación con luz natural, luces de video y flashes con buena y mala visibilidad. Para ayudar a perfeccionar mi técnica escaneé aviones, camiones, grúas, un autobús y algunos automóviles y luego avancé un poco más y comencé a capturar imágenes dentro de naufragios pequeños. Viajé a los Grandes Lagos para escanear mis primeros naufragios, incluso el Sandusky, the Maitland y el Joseph S. Fay. Los resultados satisfactorios me volvieron una fanática de la fotogrametría y me inspiraron para crear modelos de más naufragios, incluso algunos en puntos más profundos.

Uno de mis naufragios favoritos en los Grandes Lagos es el Cornelia B. Windiatesituado a 56 metros (185 pies) de profundidad en el lago Hurón. Desapareció en 1875 con su tripulación de 9 personas. Sabía que este naufragio intacto sería una imagen interesante como un modelo 3D. Entre los desafíos estaban la profundidad, el tiempo de fondo limitado a 56 metros (185 pies), el agua fría a 3 °C (38 °F) y no saber qué visibilidad y luz ambiental habría una vez que llegáramos allí. Pensé en el desafío final por un año: cómo capturar los tres mástiles en pie. Rodear los tres mástiles para obtener la cobertura necesaria sería uno de los problemas principales, pero tenía un plan, y nunca sabes qué sucederá si no lo intentas.

Imaginé cómo sería el buceo una y otra vez durante meses. Si usaba mi rebreather (recirculador) y Trimix tendría unos 35 minutos para intentar capturar el barco de 42 metros (139 pies) de largo. Tener a un buzo de emergencia nadando detrás de mí para observarme en caso de que hubiera alguna emergencia me permitiría concentrarme en mi rebreather y capturar las imágenes necesarias sabiendo que tendría a alguien confiable conmigo si necesitaba ayuda.

Mi cámara estaba lista cuando descendimos hasta el naufragio, y estaba feliz de tener luz ambiental ese día. Aun así, utilicé mis luces de video Light & Motion para ayudar a iluminar el barco para poder apreciar los colores porque todo estaba muy oscuro y tenía un color gris azulado a esa profundidad. Comencé a fotografiar en la popa cerca de la yola para asegurarme de cubrir eso completamente, y luego empecé a nadar a lo largo del fondo del casco, mientras escuchaba el ritmo de mi temporizador de intervalos disparando. Mientras nadábamos, me aseguré de superponer cada imagen en un 50 a un 80 por ciento, algo de crucial importancia. Para cuando terminamos la primera pasada, estábamos avanzando según lo previsto.

La siguiente pasada fue alrededor de la borda, fotografiando hacia abajo en un ángulo de 45 grados para abarcar las anclas de proa, el bauprés roto, el camarote de popa, las vigotas y el timón. La última pasada fue aproximadamente 2,4 metros (8 pies) por encima de la cubierta, apuntando directamente hacia abajo en cada dirección para capturar los últimos detalles. Cada vez que nadábamos junto a un mástil, intentaba fotografiar rodeando la totalidad del naufragio en la mayor medida posible. Los mástiles se elevan a una altura de al menos 9 metros (30 pies), por lo que hacer una pasada más arriba no era una opción. Al final del buceo, pasé un poco más de tiempo alrededor del timón y los mástiles para asegurarme de haberlos cubierto completamente. Después de un tiempo de fondo de 37 minutos, teníamos 60 minutos de descompresión, por lo que era hora de despedirnos del Windiate.

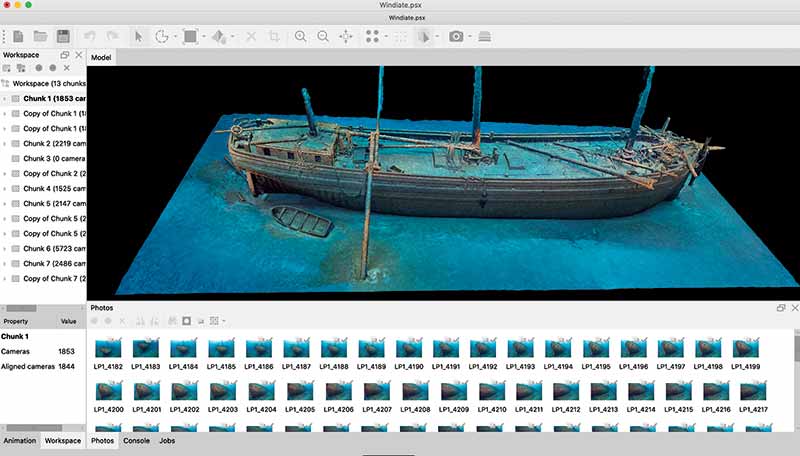

Esa noche descargué y procesé las 1.844 imágenes y las importé a Agisoft para comenzar con el modelo. Alinear las imágenes demora horas, pero una vez que este paso está completo se puede ver lo que se conoce como nube de puntos, que es el primer intento de crear una representación 3D de todas las fotos juntas. El resultado debería ser algo similar a un naufragio, lo que significa que la cobertura fue buena. Si todas las fotos se alinean bien, tendrá más puntos y detalles.

Instantáneamente pude ver que los mástiles estaban allí, pero no quería emocionarme demasiado hasta haber completado el siguiente paso de procesamiento: crear una nube densa. Esta nube densa puede demorar más de 12 horas dependiendo de la calidad de las fotos y la potencia de procesamiento de su computadora. Después de ese paso puede demorar otro día en procesar la malla y la textura. Después del buceo, pueden transcurrir tres días o más antes de poder ver el producto terminado.

El proceso no siempre se desarrolla sin inconvenientes, y puede haber una gran curva de aprendizaje desde la captura de las imágenes hasta su procesamiento. La etapa de procesamiento es diferente al procesamiento posterior habitual de una imagen —trabajo en el balance de blancos y luego incremento las sombras y reduzco los reflejos. Las imágenes terminan viéndose bastante planas y nada que ver con lo que se esperaría de fotografías normales. No es necesario que las imágenes se vean perfectas; lo importante es que el software pueda unir los puntos, para que las imágenes no estén subexpuestas o sobreexpuestas.

No podía estar más feliz cuando vi el modelo terminado y me di cuenta de que mi intento de cubrir la totalidad del naufragio, incluidos los mástiles, indicaba que había superado muchos desafíos con éxito. Llevar a cabo el buceo incluyó años de experiencia en buceo técnico, agua fría, rebreathers y mezclas respiratorias, así como también la gran cantidad de tiempo que pasé bajo el agua con una cámara.

Es emocionante producir algo que permite a los buzos y aquellos que no lo son realizar un buceo virtual en el naufragio. Puede explorarlo con gafas de realidad virtual o en su teléfono, tableta o computadora portátil para ver la totalidad del naufragio, incluidos detalles como la forma en que el timón está suspendido sobre el fondo. Investigadores y otras personas pueden usar la fotogrametría para hacer un seguimiento de los naufragios con el tiempo para ver los cambios. A veces estudiar los modelos incluso puede conducir a descubrimientos.

Hoy puedo sostener en mis manos una réplica impresa en 3D del Cornelia B. Windiate . Mi marido, David, ha estado trabajando conmigo para imprimir modelos en casa. Este proceso puede demorar otros tres o cuatro días y tiene su propia curva de aprendizaje y lista de retos. Ha utilizado diferentes materiales y temperaturas y ha probado distintos tamaños y soportes para piezas como el largo bauprés.

Avanzar desde el buceo en el Windiate en las frías e inquietantes profundidades hasta crear el modelo fotogramétrico y sostener una réplica física es un trabajo gratificante. Tener una forma realista y tangible de interactuar con un naufragio es una manera excelente de dar vida a los naufragios y compartir sus historias con todo el mundo.

Para ver el modelo terminado del Cornelia B. Windiate y otros naufragios, visite https://skfb.ly/opyqW y https://sketchfab.com/BeckyKaganSchott.

© Alert Diver - Q3/Q4 2021