Preparación para buzos y operadores de embarcaciones de vida a bordo

El 2 de septiembre de 2019, el pequeño buque de pasajeros Conception se quemó hasta la línea de flotación cerca de la Isla Santa Cruz, California, y 34 personas perdieron la vida. Este no fue el primer incendio de una embarcación de vida a bordo, pero las reacciones temerosas frente a esta tragedia mortal hicieron eco en toda la industria del buceo. Los incendios en embarcaciones de vida a bordo que se produjeron desde este incidente han alimentado aún más las preocupaciones de la industria.

Las investigaciones que se realizaron tras la tragedia del Conception revelaron varios factores que probablemente contribuyeron al incendio y la cantidad considerable de víctimas mortales, lo que dio lugar a una actualización del Código de Regulaciones Federales (Code of Federal Regulations, CFR) y nuevas normas de seguridad contra incendios de la Guardia Costera de los Estados Unidos (U.S. Coast Guard, USCG) para ayudar a los buzos y operadores de embarcaciones de vida a bordo a estar más preparados para enfrentar un incendio o una evacuación.

Conclusiones derivadas del incidente del Conception

La Junta Nacional de Seguridad en el Transporte (National Transportation Safety Board, NTSB) publicó un análisis detallado del incidente del Conception en su Informe de accidentes marítimos (NTSB/MAR-20/03), que identificó varias causas de la grave pérdida de vidas.

Los investigadores creen que el incendio se inició en el salón situado directamente encima del camarote donde había personas durmiendo. Ambas salidas del camarote bajo cubierta conducían al salón. Las alarmas contra incendios del camarote no se activaron hasta que el incendio se había hecho bastante intenso, por lo que ambas vías de escape probablemente eran inaccesibles antes de que las alarmas despertaran a alguien.

• Detección de incendios: solo el camarote, como único espacio de alojamiento nocturno, debía tener detectores de humo.

• Vías de escape: las dos vías de escape del camarote conducían al salón.

• Ausencia de una patrulla itinerante: cuando se produjo el accidente no había ningún miembro de la tripulación despierto ni patrullando.

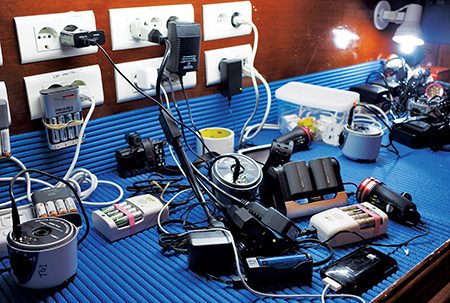

• Operaciones de manipulación segura: la fuente de ignición probable fueron las estaciones de carga de baterías del salón, aunque un informe confidencial de la Agencia de Alcohol, Tabaco, Armas de Fuego y Explosivos (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives) supuestamente sugiere que el incendio se inició en un bote de basura de plástico situado en el salón.

• Supervisión ineficaz de la empresa: los informes indican una falta de capacitación de la tripulación y procedimientos y simulacros de emergencia.

Orientación para buzos

Las lecciones aprendidas a partir del incidente del Conception Conception y otros incendios de embarcaciones de buceo pueden ayudar a orientar las medidas que puede tomar para garantizar su propia seguridad.

• Conozca sus vías de escape.

— Asegúrese de que la tripulación le dé instrucciones de cómo salir de los salones de estar. Debe haber al menos dos vías sin obstáculos para salir. Si bien la tripulación puede hablar sobre la ubicación de las salidas de emergencia, estas salidas a menudo no son visibles o pueden ser difíciles de utilizar. Diríjase a las salidas y, de ser posible, ábralas para asegurarse de que funcionen correctamente. Recuerde que los incendios producen humo negro y oscuridad.

• Siga los protocolos de baterías recargables del operador de la embarcación de buceo.

— Muchas embarcaciones han implementado nuevas normas sobre dónde cargar baterías, por lo que siempre debe conocerlas y seguirlas.

— Lleve sus propios cargadores del fabricante de equipos originales. Antes de irse de su casa, consulte sobre el suministro de energía de la embarcación, incluso el voltaje, la energía/corriente y la frecuencia.

• Consulte sobre los protocolos de vigilancia contra incendios durante la noche de la tripulación y observe al personal en acción.

• Tómese los simulacros en serio y ofrézcase para ayudar a la tripulación a realizarlos. Todos los buques deben llevar a cabo simulacros de emergencia, lo que incluye situaciones de incendio, caída de personas por la borda, buzos desaparecidos o abandono del buque. La tripulación puede pedirle que realice algunas funciones básicas para familiarizarse con el equipo de emergencia.

— Compruebe la ubicación de los chalecos salvavidas y aprenda a colocárselos.

— Localice los extintores de incendios de las áreas de estar de la embarcación.

— Si el operador no realiza un simulacro de incendio o al menos una inspección y un informe de seguridad, asegúrese de consultar al respecto.

• Considere llevar un monitor de monóxido de carbono portátil y económico para mayor seguridad cuando su camarote esté bajo cubierta. Este dispositivo también puede evaluar la mezcla respiratoria de un cilindro sospechoso.

• Mantenga los siguientes artículos cerca de su almohada y listos para agarrarlos en una emergencia:

— linterna resistente al agua

— una “bolsa de viaje” (go bag), que es una bolsa impermeable de no más de 2 litros (para que no le dificulte la salida) que contiene su pasaporte, medicamentos diarios, tarjetas de crédito, teléfono, lentes y otros artículos importantes

— campana extractora (de gases)

— En algunos casos el operador de la embarcación puede ordenarle que deje todas sus pertenencias, por lo que debe consultarles al comienzo de su viaje.

Orientación para operadores de embarcaciones de vida a bordo

El Informe de accidentes marítimos de la NTSB sobre el incendio del Conception Conception incluía varias recomendaciones que la USCG adoptó como norma provisional (USCG-2021-0306) en diciembre de 2021 y que más tarde se incorporaron al CFR (46 CFR: capítulo 1, subcapítulos K y T).

Leer y comprender el CFR puede ser complejo. El siguiente resumen puede ayudar a los operadores a entender los cambios del CFR, a quién se aplican y las fechas límite para su implementación, que eran escalonadas porque el cumplimiento de algunos cambios resultaba más minucioso.

• Implementación para el 28 de marzo de 2022

— Realizar simulacros de evacuación de emergencia de pasajeros.

— Colocar un cartel de seguridad de pasajeros (incluso planes de evacuación) en todos los espacios de alojamiento.

— Desarrollar procedimientos de manipulación para el manejo y almacenamiento seguro de artículos potencialmente peligrosos tales como baterías recargables.

— Desarrollar y ejecutar simulacros de evacuación de emergencia y de extinción de incendios de la tripulación.

— Presentar un plan para la instalación de dispositivos de monitoreo para asegurarse de que los miembros de la patrulla itinerante estén despiertos. La USCG trabajará con el operador para determinar un cronograma de implementación razonable.

• Implementación para el 27 de diciembre de 2022

— Instalar sistemas de detección de incendios interconectados en todos los espacios donde los pasajeros y la tripulación tengan acceso habitualmente.

• Implementación para el 27 de diciembre de 2023

— Proporcionar dos vías de escape sin obstáculos que no estén ubicadas directamente sobre un camarote ni dependan de él. Las vías de escape deben ser independientes de modo tal que un incidente no bloquee ambas salidas.Antes de estos cambios del CFR, la USCG había implementado normas de seguridad relevantes, incluso requisitos para extintores de incendios portátiles, en marzo de 1996, y solo eran aplicables a buques construidos recientemente. Las normas de 1996 y las de 2021 actualmente son aplicables a todos los buques de pasajeros pequeños que operen en las rutas costeras o marítimas de los Estados Unidos o que tengan alojamiento durante la noche para pasajeros, independientemente de la fecha de construcción.

Antes de estos cambios del CFR, la USCG había implementado normas de seguridad relevantes, incluso requisitos para extintores de incendios portátiles, en marzo de 1996, y solo eran aplicables a buques construidos recientemente. Las normas de 1996 y las de 2021 actualmente son aplicables a todos los buques de pasajeros pequeños que operen en las rutas costeras o marítimas de los Estados Unidos o que tengan alojamiento durante la noche para pasajeros, independientemente de la fecha de construcción.

Las normas de la USCG solo se aplican a los buques registrados en los Estados Unidos y aquellos que operen en sus aguas territoriales. No obstante, todos los operadores de buques pueden consultar estas normas para evitar incidentes trágicos.

Podemos mejorar la seguridad en el buceo a través de las enseñanzas que nos deja la historia.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2024