Hasta el año pasado, nunca había visto un pulpo durante un buceo. Eso puede no ser una sorpresa para la mayoría de los buzos —después de todo, los pulpos se refugian en pequeñas guaridas, son excelentes para camuflarse y están mayormente activos durante la noche. No obstante, estoy más interesado en ver un pulpo que la mayoría de los buzos. Soy teutólogo: un biólogo que estudia los pulpos, los calamares y sus parientes (conocidos colectivamente como cefalópodos). Nunca haber visto un pulpo durante un buceo parecía una mancha en mi carrera, por lo que decidí solucionar este problema y realizar algunos buceos fantásticos en el proceso.

Criamos algunos pulpos desde que eran huevos en el Laboratorio de Biología Marina (Marine Biological Laboratory) en Woods Hole, Massachusetts, para estudiar cómo sus cuerpos se aclimatan a los cambios ambientales. Una de las muchas cosas fascinantes acerca de los pulpos es que aparentemente el capítulo de los libros de texto de la escuela secundaria que describe cómo funcionan los genes no se aplica completamente a ellos.

Se supone que la información en el ADN de un animal se copia fielmente al intermediario temporal conocido como ARN antes de que el ARN se convierta en una plantilla para fabricar una proteína. Sin embargo, los cefalópodos se vuelven realmente creativos con su ARN. La mayoría de los animales hace a lo sumo unos cientos de ediciones en su ARN, lo que ajusta la composición de las proteínas resultantes. Sin embargo, los cefalópodos hacen miles de estas ediciones y, por consiguiente, modifican miles de estas proteínas para apartarse de lo que esta codificado en sus genomas. ¿Cómo y por qué hacen esto?

En nuestro laboratorio descubrimos que la temperatura del agua influye en muchas de estas ediciones, pero criar pulpos con una calidad del agua cuidadosamente controlada y un horario de alimentación rutinario no representa el mundo real. Quería confirmar que estos efectos que veíamos en el laboratorio estaban, en efecto, presentes en las poblaciones silvestres.

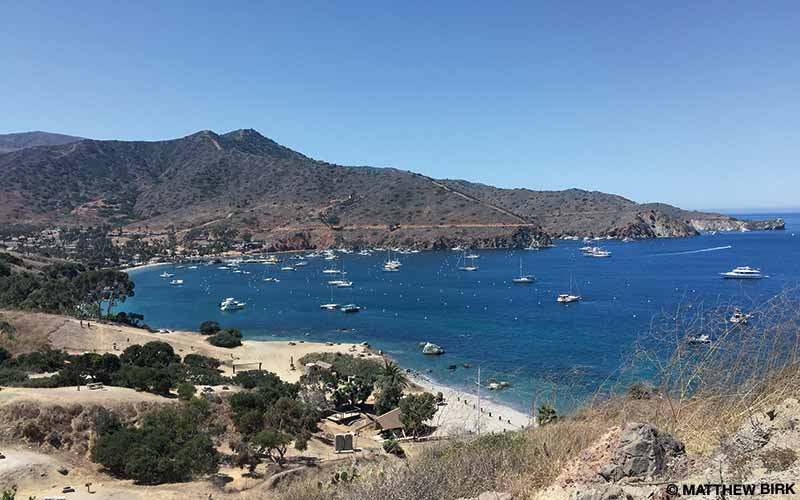

Al nunca haber visto un pulpo durante un buceo, sabía que necesitaba un poco de ayuda para encontrar uno y así poder determinar si exhibían características similares. La persona perfecta era Jenny Hofmeister, Ph.D., una científica ambiental del Departamento de Peces y Vida Silvestre de California (California Department of Fish and Wildlife), que hizo su trabajo doctoral sobre pulpos en la Isla Santa Catalina cerca del sur de California. Ella no solo sabría dónde encontrarlos, sino que también podría ayudarme a obtener un permiso de recolección científica para esta investigación, financiada por la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias (National Science Foundation).

Mientras viajábamos al punto de buceo, definí mis objetivos, investigación y cronograma, mientras Jenny y su discípulo, Mohammad Sedarat, compartían sus secretos para la búsqueda de pulpos. Con frecuencia no buscamos al pulpo en sí, sino recovecos atractivos que puedan ser una excelente guarida. Los pulpos buscan algún lugar que sea lo suficientemente grande como para acomodarse holgadamente pero no demasiado amplio como para que un rocote sargacero (Sebastes atrovirens) rapaz pueda seguirlos e ingresar en él. Una vista buena y clara libre de algas es fundamental, y una salida trasera es una característica interesante. No espere toparse con un pulpo deambulando por el arrecife. Piense en usted mismo como un vendedor de puerta a puerta que controla todos los potenciales hogares que encuentra.

Sabía que una vez que encontrara un pulpo sería un desafío hacerlo salir de su cómoda guarida y lograr que cayera en mi acogedora bolsa de malla. También tenía que encontrar la misma especie que habíamos criado en el laboratorio: el pulpo de dos puntos de California (Octopus bimaculoides). Afortunadamente, Jenny y Mohammad están entre los mejores en lo que se refiere a identificación. El truco es distinguirlo de una especie relacionada muy estrechamente, el pulpo café de Baja CaliforniaOctopus bimaculatus). Su apariencia, hábitat y su ecología son tan similares como sus nombres científicos, a menos que encuentre a una hembra protegiendo sus huevos. Los recursos en línea le indicarán que observe el anillo azul iridiscente que exhiben cuando están estresados y considere si los encontró en entornos arenosos o rocosos, pero estos marcadores de identificación no son muy confiables. En cambio, confié en los ojos experimentados de mi guía y esperé la “A” en lenguaje de señas para el Octopus bimaculatus o la “O” para el bimaculoides.

Encontramos una guarida e identificamos el primer animal. Inyectar una pequeña cantidad de vinagre blanco en la guarida detrás del pulpo tal vez lo haría salir de su refugio, así que encontré un lugar para vaciar mi jeringa de 50 ml, con la esperanza de no hacer que se metiera aún más. Esperé intentando verme lo más inocente que podía. El pulpo bombearía el vinagre fuera de su guarida con su sifón o bien intentaría escapar. Pero primero se aseguraría de que no hubiera moros en la costa. Lo vi deslizarse poco a poco fuera de la guarida, y luego lo agarré rápidamente para meterlo en la bolsa. Tuve muchos fracasos pero suficientes éxitos para finalmente regresar a la embarcación con algunos animales para estudiarlos.

Con los pulpos guardados de manera segura en una cubeta sellada, nos dirigimos de regreso a nuestra base de operaciones en el Centro de Ciencias Marinas Wrigley de la Universidad del Sur de California (University of Southern California Wrigley Marine Science Center) para estudiar a los animales.

A medida que pasaron los días de búsqueda de pulpos entre los abundantes paisajes submarinos de las Islas del Canal, la belleza y la enorme alegría de bucear en esta parte especial del mundo me dejó anonadado. Mi viaje fue científicamente productivo, y finalmente pude ver una infinidad de pulpos mientras buceaba, pero tuve que visitar Catalina durante la época más fría del año para confirmar que la edición sensible a la temperatura estaba ocurriendo en las poblaciones silvestres.

En febrero del año siguiente regresé a la isla para recolectar más animales cuando la temperatura del agua había bajado unos grados en comparación con el verano anterior. Después de ese segundo viaje, una vez finalizada mi recopilación de datos, me encontré deambulando por el aeropuerto de Los Ángeles a principios de marzo del año 2020. Escuché una breve noticia sobre un brote de un nuevo virus, y me pregunté al pasar si debía lavarme las manos un poco más por si acaso.

Trabajar a la vanguardia de la ciencia puede ser muy emocionante, pero también puede ser sumamente frustrante. Pero resulta que incluso los mejores expertos del mundo a veces pueden estar equivocados. Después de toda mi codificación de barras de ADN descubrí que todos los pulpos que habíamos capturado eran Octopus bimaculatus y no la especie bimaculoides que eran mi objetivo. Nadie tiene la culpa —todos sabíamos lo difícil que es identificarlos correctamente.

En muchos sentidos, esa es la belleza de la ciencia. Nuevos datos pueden mostrar que no comprendemos la naturaleza tan bien como creemos. Nuevos hallazgos pueden hacer que reevaluemos lo que creemos que sabemos sobre el hermoso e inmensamente enigmático mundo submarino que los buzos tienen el privilegio de explorar. Actualmente, en lugar de simplemente confirmar los estudios realizados en el laboratorio, estoy explorando cómo la edición del ARN evoluciona mediante una investigación de ambas especies estrechamente relacionadas.

Esta es la esencia de cómo la ciencia funciona realmente: los esfuerzos científicos a menudo son el camino más sinuoso para obtener una respuesta que no se estaba esperando a una pregunta que inicialmente no se tenía pensado formular. Pero después de este recorrido engorroso llega el descubrimiento de lo desconocido y el progreso hacia una mejor comprensión de nuestro mundo.

© Alert Diver - Q3/Q4 2021