Ce que l'art et les nudibranches peuvent nous apprendre sur le réchauffement climatique

Ville d'origine : New Haven, Connecticut

Années de plongée : 56 (J'ai plongé pour la première fois à l'âge de 9 ans à Tahiti).

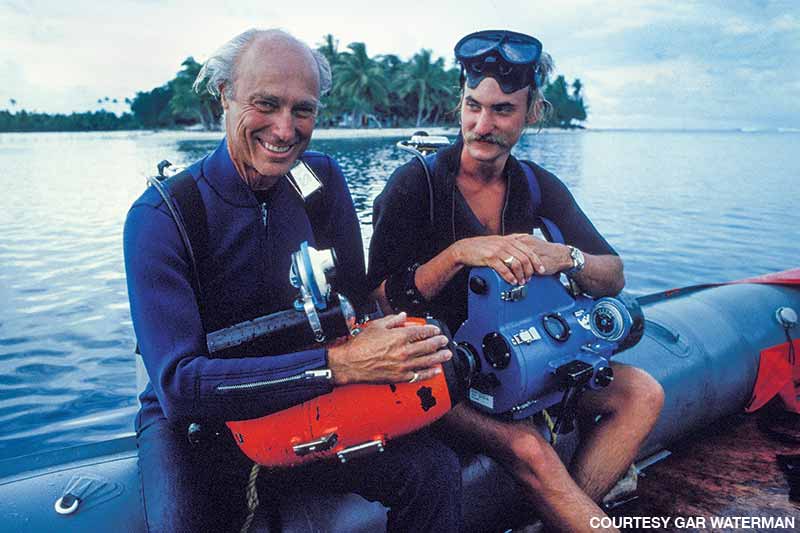

Destination de plongée préférée : Probably the Revillagigedo Islands. I had a memorable dive there with my dad for the Discovery Channel special in 1990 — giant mantas and crystal-clear water with driving clouds of volcanic ash and the extraordinary topography. I hope to get back there someday.

Pourquoi je suis membre de DAN : Should anything go wrong while diving in remote locations, getting help can be a huge challenge. DAN gives you a worldwide network to identify the closest and best help as quickly as possible. Bent in the Banda Sea off Irian Jaya? If anyone can help you there, it’s going to be DAN.

Connus pour leurs couleurs, leurs motifs et leurs formes frappantes, les nudibranches se trouvent dans les mers du monde entier. Ces mollusques marins à corps mou, souvent appelés limaces de mer, sont les sujets préférés des photographes sous-marins. Ils ont également captivé l'imagination du sculpteur Gar Waterman, fils du légendaire cinéaste Stan Waterman.

Gar’s fascination with sea slugs extends beyond his aesthetic appreciation for their unique, organic form. Because most of them have a life span of less than a year and adapt rapidly to changes in their environment, scientists have found them to be an “indicator species” — an organism whose presence, absence or abundance reflects a specific environmental condition. In this case, nudibranchs are helping researchers understand the impact of global warming on ocean health.

Avec chaque nudibranche qu'il a taillé, ciselé et poli dans la pierre, Waterman espère communiquer leur beauté excentrique et leur rôle scientifique. Pour les créer, le sculpteur de New Haven, dans le Connecticut, s'appuie sur les images prises par des photographes sous-marins et sur les souvenirs qu'il a gardés des expéditions de plongée qu'il effectuait avec son père.

Une année magique

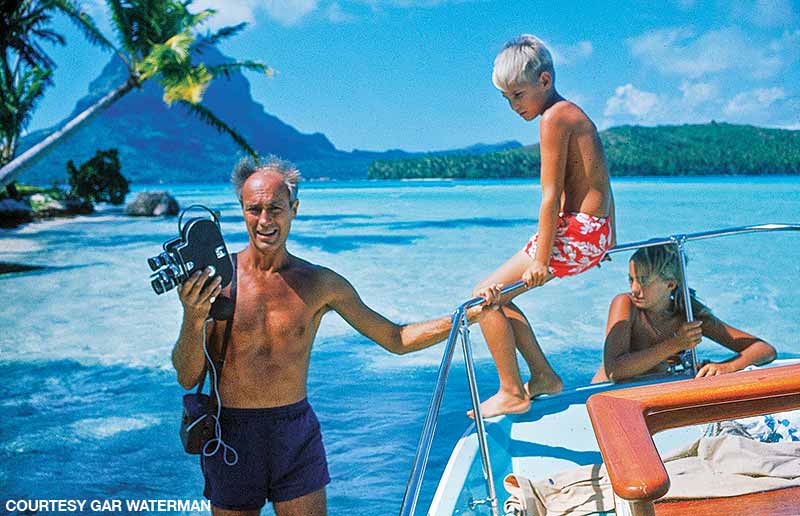

Waterman grew up in Princeton, New Jersey, and spent idyllic summers in Maine, but in 1965, when he was 9, his father moved the family to Tahiti and documented the adventure for National Geographic. It was the younger Waterman’s first experience diving.

“At the time, I was just following what we were told to do,” Waterman recalled. “You don’t have much perspective at 9 years old. We were going to someplace in the South Pacific and had some knowledge that this was unusual — we left school and our routines. This work was what the old man did, and we were going. Of course, it couldn’t be anything but an extraordinary year for all of us. I remember so many different pieces of it so clearly, while the years before and after are a blur. I was not cognizant at the time how privileged I was to have that experience, but it established a visual vocabulary for me and was the beginning of my love for all things underwater.”

Over the years Waterman joined his father on other expeditions, but it was his year in French Polynesia that would inform and inspire his work. “That year was a foundation in terms of imagery long before I realized I would spend my life as a sculptor,” he said. “I am still drawing on that visual database for my work today.”

Le cœur de pierre

When Waterman was 10, his family returned to the United States; he eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in French from Dartmouth College.

“My drift toward art and science has evolved over my lifetime, similar to how I became a sculptor,” he said. “It was not a conscious decision. It was a brief bit of self-reflection where I realized I was happiest when I was making things. Everything pointed in that direction.”

Following his college graduation though, Waterman was admittedly adrift. “I spent a summer in Maine, and then fall came around, and I didn’t have a clue as to what I’d do,” he said. “I struggled into a routine and did some work in film with my brother and dad. I was just a grunt, and there was always something voyeuristic about it that lacked actual engagement — you come in with your camera, get the best of whatever you’re there for, and then you leave.”

Waterman set up a small studio in a friend’s garage in Princeton and began tinkering. At this point he made a pivotal decision in terms of becoming a working artist. “I met a sculptor who was a friend of my college roommate, and he told me about Pietrasanta, Italy, and said you could learn to carve stone there,” Waterman said. “I had some money from my film work, so I decided to go. It ended up being one of the best decisions I ever made. I was just one of many would-be sculptors — old and young, famous and unknown — who were there because of the stone.

“I ended up going back and forth for seven years. I would sell enough sculptures when I came home to make enough to go back, and without ever reaching some epiphany that I was going to be an artist, that’s what I became.”

La série des limaces de mer

Though Waterman hasn’t dived in many years, the influence of his year in French Polynesia and on other expeditions is unmistakable in his nudibranch sculptures and ones he’s created of shells, fish and other marine life.

“Working with my father, we were typically looking for the bigger creatures for his film,” Waterman said, “but I loved settling down on the bottom when I could and looking closely at the reef to see what was there. I’ve always loved spotting some of the tinier creatures — shrimps, nudibranchs and the like. As I evolved into creating this series of slug sculptures, I realized there could be a way to add an environmental inflection to the work and bring some relevance into it beyond just creating fine art objects.”

The nudibranchs have been the stars of past exhibits, including the recent “A Slug’s Life: Facing the Climate Endgame” at the Maritime Aquarium in Norwalk, Connecticut.

He hopes the sculptures not only raise awareness but also “promote some kind of actual engagement in the process of trying to preserve the natural world and all these little ‘beasties’ that are likely to be lost to ocean acidification,” he said. “It can be a challenge to make a positive presentation because if you’re all doom and gloom, people turn off. You’ve got to capture their attention without actually saying, ‘These creatures are probably all going to die because of what we are doing to the environment.’”

Art inspired by nature is the oldest art movement around, and I feel strongly that my work forms a part of that continuum. Any nature-inspired artist today should be trying to find some way to have their work join the rest of the voices out there making a case for greater environmental awareness, otherwise their subject matter may well be gone before they realize it.”

En savoir plus

Visit Gar Waterman’s studio in this video.

© Alert Diver — Q3/Q4 2021