To pee or not to pee? That is not the question for technical divers, instructors, or others who spend long hours in the water. Proper hydration and comfort ensure that urine will flow. The question is, What’s the best way to handle it?

Wetsuit divers never have a problem. As everyone knows, though not everyone admits, peeing in a wetsuit is easy. You just let nature take its course and rinse the suit later. Fortunately, drysuit divers now have reliable means to relieve themselves underwater, and the drysuit relief zipper has largely become outdated.

Before we review the options, it’s useful to consider why the ability to urinate underwater is essential for divers. First, proper hydration plays a vital role in helping the body facilitate offgassing and avoid decompression illness (DCI); you don’t want to be dehydrated when diving. Not drinking to avoid urinating is counterproductive, and drinking fluids can help ameliorate the effects of seasickness.

Second, the ability to urinate at will removes a potential stressor from the dive and adds to the diver’s comfort. Finally, not having to remove your suit before or between dives to empty your bladder is convenient and in some cases can save potential embarrassment — for example, if facilities aren’t available.

A Wee Bit of History

Male commercial divers had an in-water urinary solution as early as 1876. Legendary British equipment manufacturer Siebe Gorman & Co. Ltd. touted a portable urinal in its 1909 catalog. According to the entry, the pouch-like device, which male divers attach with a belt, was constructed so “the diver can urinate without fear of the urine entering his dress, no matter what position he may be working.”

Early drysuit-wearing cave explorers — predecessors of today’s tech divers — were slow to heed the call of nature. Longtime cave diver Paul Heinerth, a member of Bill Stone’s original 1987 Wakulla Project, said exploration divers would hold it until they were in the decompression habitat and could urinate out the hatch into the water.

They didn’t regard adult diapers as an acceptable solution. The late, great underwater filmmaker Wes Skiles, also at Wakulla, once sheepishly explained to me that they were “too stupid or embarrassed” to use diapers. Legendary cave explorer Sheck Exley used a wetsuit supplemented with chemical heaters or his red Parkway neoprene drysuit so, according to him, he could “just cut it loose” on extended exploration dives.

Adult diapers were briefly popular in the early 1990s as tech diving emerged from obscurity and divers ventured deeper and longer. With the invention of the P-valve in the mid-1990s, however, the new technology quickly gained a following. Numerous homemade P-valve designs iterated on the basic idea: a one-way valve with a tube connected to a self-adhering external catheter for males to evacuate urine from a drysuit.

Commercial products soon replaced these do-it-yourself versions. Extreme Exposure in High Springs, Florida, had one in the late 1990s, which they later transferred to Halcyon Dive Systems. It didn’t take long for P-valves and condom catheters to become the norm for male tech divers.

Unfortunately, female tech divers were stuck with diapers or nothing at all until 2006, when Netherlands diver Heleen Graauw invented the first external catheter system for female divers. It was a soft, flexible cup that divers attached with medical adhesive and connected to a P-valve. Graauw soon teamed with surgical technician and underwater filmmaker Laura James, who helped perfect the adhesive system and assisted with marketing. The co-owner of Zero Gravity Dive Center in Mexico dubbed Graauw’s device the She-P, and the name stuck. Graauw changed the material in 2008 to blue hypoallergic silicon and later added more colors.

Current Technology

P-valves and condom catheters have become standard for males in the cave and tech communities. They are popular with instructors, photographers, and scientific and public safety divers who spend long hours in the water. Most drysuit manufacturers supply P-valves as an option, and divers can easily install third-party valves.

Male divers carefully roll a self-adhering condom catheter onto their penis, making sure to get a proper seal. The catheters are disposable and come in various sizes, so choose a size that fits snugly. Next, the end of the catheter attaches to the tubing connected to the P-valve, which divers wear on the left or right thigh. The tubing lies flat against the torso and leg so it won’t get pinched. Finally, the diver rotates the P-valve to the open position, and then they are ready to go.

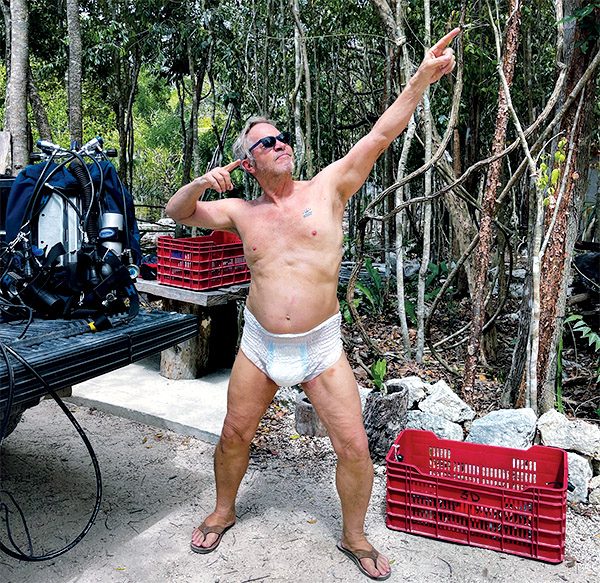

Condom catheters typically last for a day of diving if they are the correct size and divers put them on carefully. But that’s not always the case in hot, humid weather, when it’s not uncommon for the catheter to slip off during diving. If that happens while urinating, it can turn a dry dive into a wet one. Divers can try to solve that problem by applying the catheter in the morning right after showering or by using a smaller size. Some divers, myself included, prefer to use a disposable adult diaper in hot weather. They’re easy to put on, don’t slip off, and keep the user reasonably dry.

The She-P is the only external female catheter made for diving, though divers have adapted other brands, such as the Shewee, for underwater use. The She-P is a silicon cup with a small turbulence reservoir, and divers must properly position it and use an adhesive to form a watertight seal against the body. It is less reliable than catheters for males and requires more work to prepare, position, and remove. It is not disposable — an environmental choice by Graauw — so divers have to clean it after use. The good news is that She-P offers users detailed instructions and videos on positioning and installing the device.

Once a diver has it adhered, they connect the neck to the P-valve tubing, similar to a male catheter. The company recommends that divers wear a thong, underwear, or diaper over the unit to help keep it firmly in place and to always carry a spare.

While these devices aren’t perfect, P-valves and catheters are developments that allow drysuit divers to go where no one has gone before.

© Penyelam Siaga — Q1 2024