Most blackwater divers agree it only takes one good dive to hook you. The idea of jumping off a boat at night, miles from shore, with only a few lights to guide your way might sound terrifying, but the experience is unlike anything our imaginations could conjure. Blackwater diving is an immersive experience that combines science, adventure, and photography while offering a glimpse of nature that few people get to observe.

During a nightly phenomenon called diel vertical migration,billions of zooplankton migrate vertically through the water column to feed and then return to the depths before dawn. Much of the migrating biomass is tiny gelatinous creatures, making the event visually confusing while also beautifully natural and captivating. Some plankton settle to the substrate, while others remain suspended, adding to the greater food web and supporting life at sea and on land.

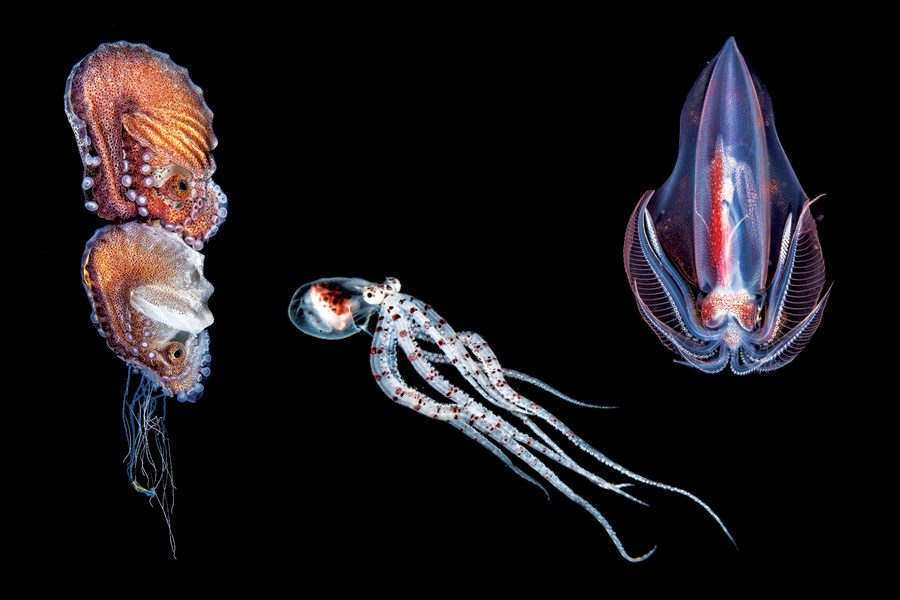

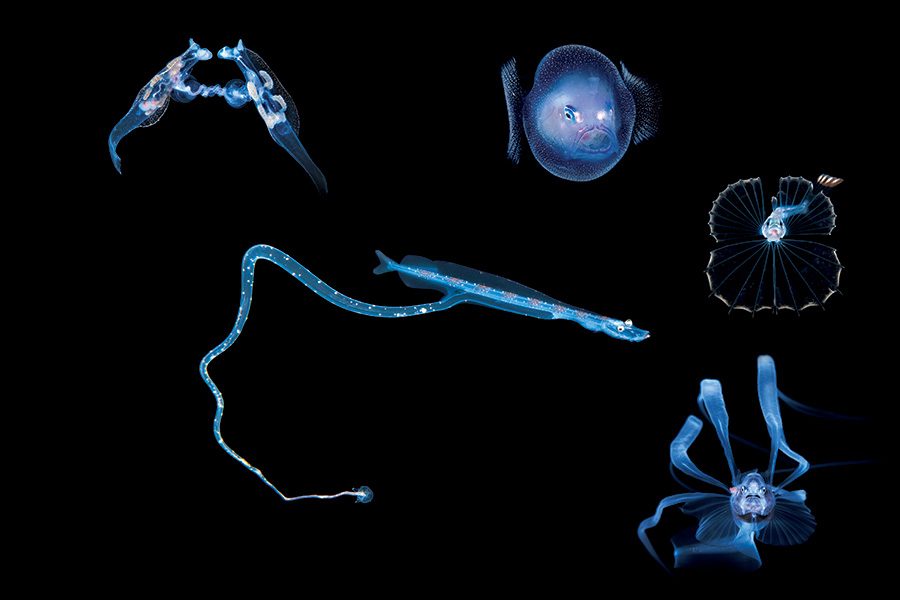

Relying on dive skills and intuition, blackwater diving is perhaps the most relaxing dive you can do. It can also be exhilarating to drift through the dark and pan your light around. Objects begin to appear; shadows shift, squids dart about hunting and inking, jellyfish undulate, and light twinkles like fireflies. The entire experience is surreal. The creatures in this world thrive in perfect order and disorder, in controlled chaos and harmony.

Blackwater diving started more than 50 years ago, when a handful of adventurous divers in Kona, Hawai‘i, began exploring the open ocean at night. Their photos from those early forays are legendary and still heralded as groundbreaking work. Kona has become ground zero for blackwater diving, which is still very active and productive there.

The Blackwater Photo Group formed on Facebook in 2017 to connect active blackwater divers. The idea was to have a forum to discuss and exchange ideas, experiences, photography challenges or tips, and the natural history of what we find. The group began to grow, garnering attention from the science community. A network formed between the academic world and blackwater divers, who craved knowledge and insight into the variety of nocturnal underwater subject matter.

Shooting blackwater photos or videos is quite challenging. There is nothing to stabilize yourself, and buoyancy is critical. The ability to fin at top speed while remaining calm and keeping a clear mind is crucial as you hunt a subject that does everything it can to evade you. Each image results from a combination of concentration, dive skills, persistence, and dedication fueled by the drive to discover something that has never been seen.

Some of the most exotic subjects seem to emanate from regions with prevailing currents or quick access to deep water, such as Japan, Southeast Florida, Kona, and Anilao, Philippines. Divers continually discover other hot locations around the world.

Anyone interested in this style of diving should try it. You don’t need to be a professional or own the most expensive camera to enjoy a blackwater dive, but you will need proficient dive skills along with a good light, a macro lens, and a strong sense of adventure.

Mike Bartick

Anilao, Filipina

saltwaterphoto.com

I love all kinds of photography, but I’m obsessed with blackwater images. I have recently started using video to document movement and behaviors.

I started blackwater diving in 2016 in Anilao, Philippines, doing shore-based blackwater-ish diving using stationary lights to attract subjects. The guides and I developed a downline method for the area; after a year and many blackwater dives, we began discovering the best places for blackwater subjects. The richest areas are in less than 1,000 feet (305 meters) of water.

The bay opens to the Verde Island Pass, where deep water pushes in twice a day and brings a variety of subjects. There are seasonal migrators and a regular cast of interesting planktons. Our approach is to look small and find big — don’t focus only on larger subjects, as finely detailed planktons are incredibly ornate and just as fascinating.

A few of the area’s unique subjects have become iconic — such as the wunderpus we discovered in 2012 — and make Anilao a must-dive blackwater destination. We also found the first female paper nautilus and blanket octopus in the area.

After countless blackwater dives, I have realized that only one thing is for certain. As Socrates said, “The more I learn, the less I realize I know.”

Jeff Milisen

Kona, Hawaiʻi

milisenphotography.yolasite.com

Hawaiʻi is the biggest island in the most remote archipelago in the world. It has no continental shelf, so you only have to travel 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) from Kona’s shore to reach the pelagic. Conditions can be sporty on the surface away from shore but are much quieter underwater. The drift can be so passive that many divers are surprised to end up miles from where they splashed.

The draw for blackwater diving in Kona is the diversity of unpredictable subjects. Divers can be surrounded by hunting dolphins one night and stalked by a tiny cookiecutter shark or mesmerized by an endemic Fisher’s seahorse the next. A blizzard of pelagic creatures eats and is eaten by clouds of other life. Shoals of purpleback flying squids haunt the light’s edge, sometimes approaching to shred a lanternfish. The squids feed larger predators ranging from game fish and deepwater predators to oceanic sharks and mammals.

The hook has always been wildlife against a clean, black backdrop. I rely on the lightning-fast focusing of a digital single-lens reflex camera and the minuscule focusing distance of a 60mm macro lens, but plenty of people use a small GoPro camera. Advances in camera technology have made photography the easy part. The difficulty is hunting for the right subject.

The pelagic ocean is still ripe for discovery. Creatures there live in a constantly moving, fluid world and are at the whims of the wandering currents, yet they weave intimately into the systems that keep us alive. The discovery you seek awaits just offshore — you just need the courage to claim it.

Steven Kovacs

Palm Beach, Florida

instagram.com/steven_kovacs_photography

The first blackwater dives sporadically offered to adventurous divers off Palm Beach County on Florida’s eastern coast began in 2013. Those occasional experiences have expanded and now include several commercial dive operators who set off at dusk several nights a week to travel 4 to 6 miles (6.4 to 9.7 kilometers) offshore to the desired depth of 600 to 750 feet (183 to 229 meters). The crew lowers a large, illuminated buoy attached to a 60-foot (18-meter) weighted line with floodlights at regular intervals into the water to drift freely with the current. This well-lit line attracts ocean nightlife and serves as a reference point since dives in Florida are untethered.

Despite having done blackwater diving around the world, I am in awe of the sheer variety of life on my home turf. The Gulf Stream brings warm, nutrient-rich water from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean into the Atlantic Ocean, sweeping past the Florida coast. These nutrient-rich, deep ocean waters bring a wide range of pelagic animals and an incredible array of extremely rare invertebrates and larval deepwater fish, many of which rise from the depths every night as part of the diel vertical migration.

Sightings of larvae of deepwater species such as tripodfish, whalefish, anglerfish, dragonfish, and cusk-eels are among many photographers’ most coveted encounters. When mixed with the more common shallow reef inhabitants, the result is a mind-boggling variety of marine life.

I currently use a Nikon D500 with a 60mm macro lens and dual strobes on either side. I mount lights on top of the housing, using a strong, narrow beam as the main searchlight and a second, weaker light with a wider beam angle to illuminate the immediate vicinity. The low-powered wide beam can minimize the chances of overlooking animals that may be close by.

Linda Ianniello

Southeast Florida

lindaiphotography.com

I’m fortunate to live in southeast Florida, where there is easy access to diving off the coast. I have been scuba diving and taking underwater images for more than 30 years. Macro photography has always been my favorite, where finding the small, unusual subjects is half the challenge. I got interested in blackwater dives eight years ago when a local dive operator started offering them, and I have made more than 450 blackwater dives locally since then. We go about 5 miles (8 kilometers) off the coast and drift close to the Gulf Stream, where the bottom is 700 to 750 feet (213 to 229 meters) deep, but we stay within recreational limits.

It is fascinating to find and photograph the animals that migrate vertically every night to feed and those that spend their whole lives in the water column. I strive to identify and learn about them with a lot of help from willing scientists. Scientists are interested in seeing the subjects in situ rather than mangled after being collected in a net towed behind a boat.

I use a Nikon D500 and 60mm lens in a Nauticam housing with two Inon Z-330 strobes, an Inon S-2000 as a secondary strobe, and two Sola focus lights. Most subjects don’t like the lights, so this type of photography is challenging. The camera and lens provide a fast and accurate focus, and three strobes give plenty of light for transparent subjects.

I focus on the tiny, delicate subjects and their behavior, which many divers overlook. Susan Mears and I coauthored the book Blackwater Creatures: A Guide to Southeast Florida Blackwater Diving. Part of my goal is to educate people about the creatures found in this environment and the need to protect them.

Ryo Minemizu

Okinawa, Kume Island, and Izu Peninsula, Japan

ryo-minemizu.com

I started blackwater diving in Japanese waters in 1995 and now have approximately 13,000 hours of blackwater experience. My main goals are photography and film, but I also organize blackwater events for the general public to experience this unique form of diving.

The variety of creatures I have encountered on blackwater dives is fascinating. Despite plankton being just a few millimeters in size, their shapes and colors are awe-inspiring as they exist in a perfect state, drifting with the current in their natural environment.

I spend about eight hours a day in the water, both day and night, drifting and constantly pressing the shutter. My basic shooting method, especially at night, is to use a fast shutter speed, control the depth of field down to fractions of millimeters, and always pay attention to the water’s movement around the tiny subjects. Their colors and the motion of their fins and cilia, all for the sake of survival, represent life’s precious beauty born of necessity. These subjects and their details are often invisible to the naked eye, but a macro lens allows new vistas to emerge.

Blackwater dives are available from Osezaki on the Izu Peninsula and on charter dive boats from the Okinawa mainland and Kume Island in southern Japan. Southern Japan’s best season is from March to October, when the water temperatures are around 77°F to 86°F (25°C to 30°C). Blackwater beach diving in Osezaki using the bonfire technique is possible during the offseason from November through January.

We need to get serious about the problems stemming from plastic pollution in the oceans. Communicating that peril is now my most important work.

Editor’s note: In bonfire diving, divers arrange strong lights in a stationary position on the seafloor to attract plankton and creatures that feed on plankton or are drawn by the lights. Divers arrange themselves around the lights rather than doing the deepwater drift typical of a traditional blackwater dive.

© Alert Diver – Q3 2024