HER NAME WAS TOKITAE, which means “nice day, pretty colors” in the Coast Salish language. The Lummi Nation knows her as Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, which is a historical reference to the Penn Cove area, where she was captured along with other young southern resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in August 1970 near Whidbey Island, Washington, when she was about 4 years old.

The Lummi Nation along with conservation groups, animal rights activists, and others fought for years to free her from captivity and had hoped to bring her back to a sea pen in her home waters in the Salish Sea, but the beloved 57-year-old orca died Aug. 18, 2023, at the Miami Seaquarium in Florida, where she had lived for the 53 years since her capture, performing for the crowds as Lolita.

When Tokitae arrived at the Seaquarium in 1970, she joined an older male orca named Hugo, who also was captured from Puget Sound and sent to the Seaquarium two years before her arrival. They both were members of the endangered southern resident L pod.

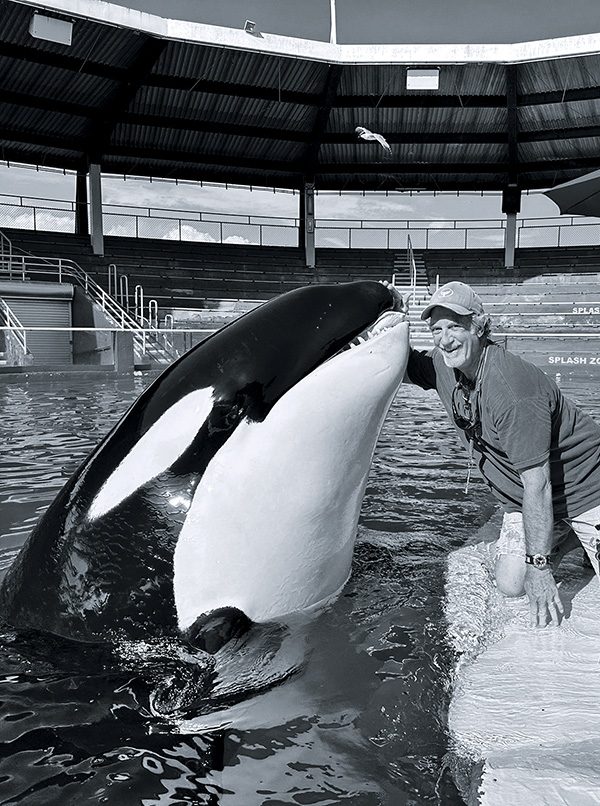

With a focus on improving the health and welfare of marine mammals in human care, conservation of wild populations, and support for global stranding networks, Stephen McCulloch has worked for five decades within both the zoological industry and conservation-research communities around the world. His relationship with Tokitae spanned 50 years. Photo Courtesy Stephen McCulloch

From 1965 to 1976, more than 100 orcas were captured in Penn Cove, Washington. Ten of these orcas were sold to marine parks, and the rest were set free. At least five orcas died during this and two other capture operations. No orcas have been captured in U.S. waters since 1976.

Hugo died in 1980 from self-inflicted injuries resulting from a brain aneurysm, likely from repeatedly hitting his head against the tank wall. Following his death, Tokitae never saw or heard another orca, remaining in a solitary existence in that sense. Her only companions were smaller cetaceans who lived and performed alongside her over the years.

For activists, Tokitae’s decades of isolation from other orcas and housing within a small, antiquated enclosure is yet another instance of animal exploitation. Though paths diverge on how best to help orcas thrive within zoological settings and in the wild, shared values and respectful dialogue are the best means to overcome significant philosophical differences. These discussions include the brutal drive fisheries and modern-day whaling practices that lead to the unnecessary slaughter thousands of whales each year.

Marine parks striving to meet animals’ needs often walk an imperfect line between contemporary ethics, education, research, and conservation goals. Incremental changes to improve husbandry, enclosure designs, and enrichment practices can enhance daily well-being within the limits of human care environments. Any facility that cannot sufficiently provide for animals in captivity may need to be upgraded or phased out — a lesson from Miami Seaquarium and Tokitae’s life and tragic death.

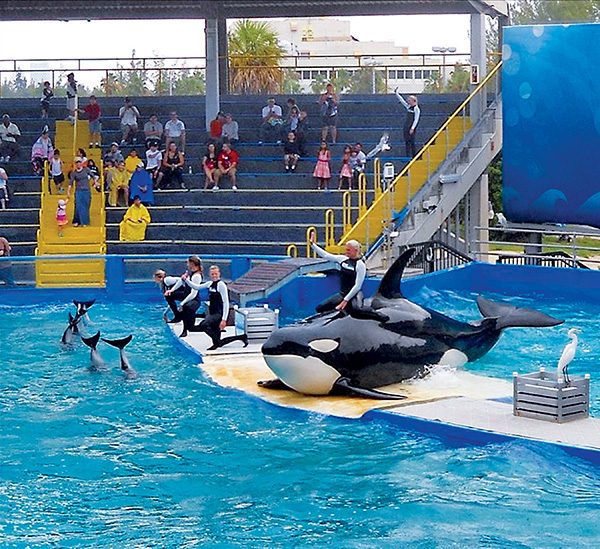

Following Hugo’s death in 1980, Tokitae was housed with other small cetaceans but remained a solitary orca until her death in 2023. Photo by Allan Watt

Just five days before her death, the Friends of Toki veterinary team reported her to be healthy. Her body condition, behavior, and bloodwork were within normal parameters. She was responding favorably to ongoing treatments for a chronic respiratory infection and fungal disease. Within the next 36 hours, however, she exhibited symptoms of gastrointestinal distress and stopped eating. Since marine mammals are masters of masking diseases in the wild, not eating is sometimes the first indication that something is wrong.

The veterinary team immediately developed a treatment plan to rehydrate her via subcutaneous fluids, deliver medications, collect a fresh blood sample, and conduct an ultrasound on her abdominal region. On Friday, Aug. 18, at 10 a.m., the water in her pool was gradually lowered to facilitate treatment. The protocols were well-known from when she was similarly treated in October 2022 during an eight-day period when she had stopped eating.

Trainers and veterinary staff continuously monitored Tokitae’s respirations and heart rate as she rested quietly on the pool bottom in waist-deep water. When the treatments were completed, the pool level was slowly raised. This time, however, she did not fully recover. Instead of resuming a normal swim pattern, she appeared lethargic and disoriented, listing to her right side and unable to manage her environment. The veterinary team immediately reviewed the bloodwork, which indicated she was experiencing acute renal failure and required additional treatment.

With several of the staff alongside her in the water to provide support, the pool water was again lowered. This time she was placed in a stretcher to better stabilize her. Over the next few hours the veterinary team administered more fluids while her trainers comforted her and monitored her vitals. But despite their best efforts, Tokitae succumbed, dying in the arms of her trainers, surrounded by animal care staff and others who had been working to rehome her to her native waters.

Despite the grief and gravity of that moment, the team quickly responded to protect the integrity of her remains and preserve the delicate biological samples that would help determine her life history and confirm the cause of death. While Tokitae was being secured, the training staff shifted their attention to her lone remaining tankmate — a 40-year-old male Pacific white-sided dolphin named Li’i, who was awaiting her return on the other side of the watertight bulkheads.

Within an hour Tokitae was lifted from the pool where she had spent 53 years and was gently lowered into a watertight container. She was packed in ice and placed aboard a refrigerated truck for transport to the University of Georgia’s College of Veterinary Medicine, where a team of marine mammal veterinary pathologists spent almost 20 hours conducting a detailed forensic examination.

Although the exact cause of death will take months to process and confirm, preliminary findings from the gross necropsy were consistent with acute renal failure and confirmed the extent of lung lesions associated with her chronic pulmonary infection.

Tokitae’s passing deeply affected her caregivers, the zoological industry, activists, conservationists, and Indigenous groups, especially the Lummi Nation. Though perspectives on her decades of captivity differ, there is a common reverence for these sentient beings. The Lummi Nation’s ancestorial connection to Tokitae represents the larger cultural role of whales for Indigenous peoples. Her captivity severed sacred bonds between nature and community.

On Sept. 20 a Lummi Nation elder accompanied Tokitae’s ashes from Georgia to Bellingham, Washington, where tribal members held a private sacred water ceremony and returned her ashes to her native waters. They plan to hold a public ceremony honoring Tokitae at a later date.

After spending 35 years at Seaquarium, Li’i is now at SeaWorld in San Antonio, where he joined other Pacific white-sided dolphins on Sept. 25.

Some people suggest that Tokitae’s legacy might catalyze developers, philanthropists, and the City of Miami to create a One Ocean, One Health Center in place of the Miami Seaquarium. A marine mammal rescue center and teaching hospital for future generations of veterinarians and scientists to convene and collaborate would be a fitting legacy and a path forward.

Humans have an obligation to place the needs of animals with which we share the Earth over the concerns of commerce. Well-operated, responsible zoos and aquariums represent a vital resource for the future of species preservation. It is a frightening prospect that zoos and aquaria might be a final repository for the DNA of creatures threatened with mass extinction in the wild.

Tokitae’s death should inspire us to assess our relationships with animals and each other. We all share a responsibility to serve as good stewards for the creatures with whom we share the planet. AD

© Alert Diver — Q4 2023