Working with models underwater has been a fundamental cornerstone of my career for more than four decades. I love shooting images of marine life, but for magazine editorial assignments, advertising photographs, and stock photography with model-released people, collaboration with a skilled underwater model has been paramount.

It’s so consistent in my work that I have wondered how many cumulative photos I have taken with models underwater. The number of clicks of the shutter is beyond calculation, but as I pondered the matter a conclusion emerged: seven. I can break it down to seven specific categories of wide-angle underwater photos with a model.

There have been thousands of images within those seven categories, each featuring different models, light, environment, and marine life — all of which keep it fresh and exciting. Not counting “divers in caves,” an inspirational genre beyond my technical diving comfort level, here are my magnificent seven categories along with specific photos that illustrate the concepts.

1. Diver with Coral Reef

This is perhaps the most common shot of the genre, and it’s one we approach with purpose or capture serendipitously. The photographer and dive buddy are enjoying a tropical reef, and the buddy becomes an accidental or intentional element of the composition. The reef is the star, and the model is the supporting cast.

Intentionally directed photos are by far the more productive, for you can establish where you want the model in the scene, direct where they should cast their eyes, and control their up/down and near/far position relative to the foreground. Sometimes when I’m traveling solo and haven’t recruited a dedicated model, I’ll find a significantly beautiful bit of reef and wait for divers to swim by. That’s a random happenstance, and the percentage of keepers is far smaller than with a directable model.

I was working with my wife, Barbara Doernbach, in the Solomon Islands, for example, and we happened upon a lovely reefscape with a crocodilefish. Barbara was extraordinarily experienced as an underwater model and knew exactly where to position herself in the near background, always careful not to impact the reef and to cast her eyes to the fish, the obvious central compositional element. I was set up with focus, light, and composition, and she was set up neutrally buoyant for as long as it took to get the shot. The fish’s yawn was a happy accident, but by being there and anticipating the possibility of interesting behavior, we caught it.

The shot of Michelle Cove with the elkhorn coral is another example. Along Southwest Reef one specific elkhorn stand was always better than the rest. I could position myself in a spot of sand, set the focus and lighting on the coral, and then Michelle would do pass after pass until the circular motion of my hand followed by one finger upraised — meaning “one more time” but often became several more times — until I replaced it with a vigorous OK sign.

2. Diver with Marine Life

This type of underwater work with models might be the most fun to do for both the photographer and the diver. The marine life dictates the shoot’s pace and proximity, and it is the job of the photographer and model to interact in a benign fashion.

Shots of this nature are often integral to destination articles for magazines such as Alert Diver. I was writing an article about Grand Cayman, and one of the most iconic illustrations happens at the Sandbar with southern stingrays. The rules have evolved over the years, and the regulations now stipulate that snorkelers not wear fins. That’s a good rule that minimizes impact on the rays, but it also means decades of previous shots were instantly dated and inappropriate.

Liz and Gary Frost of Living the Dream Divers volunteered to be my models for a new shot. We were at the Sandbar at sunrise before the cruise ship crowds arrived, so we had the attention of a much larger contingent of rays. The rays were the stars, the snorkelers established scale and interaction.

3. Product Illustration

Over the years I have shot a lot of commercial campaigns and catalogs for equipment manufacturers — including Dacor, Scubapro, Aqualung, and Henderson — as well as specialty shots where underwater was not the project’s primary focus.

The product need not be the absolute star, particularly for catalogs. Typically, the job is to portray the diver’s lifestyle, always careful to reveal the manufacturer’s logo. The real product shots that dealers use for placing orders are of gear under controlled conditions photographed in the studio.

I double-dipped on the shot of the model at night on the Superior Producer, shooting for both Underwater Kinetics for the dive light and Henderson for the wetsuit. The shot of Julie Anderson with the spotted dolphins was from a Scubapro catalog shoot but crossed genres and I’ve used as an editorial illustration as well.

4. Diver as an Element of Forced Perspective

I was once commissioned for an underwater photo, part of the “Vantage, the Taste of Success” cigarette advertising campaign. A diver holding massive gold chains was positioned toward the wide-angle lens, with the diver and shipwreck drifting off to the background. When the art director saw images processed for review, he angrily exclaimed, “My God! These are the hands that ate Chicago!” I got the hint and the next day shot the diver and the booty on the same plane of focus, rendering hand size more authentic.

The same forced wide-angle perspective that makes a foreground subject exceedingly prominent can be used to good effect. The shot of my daughter, Alexa, with a crocodile from Cuba is a good example. It rather comically gained viral outrage from nondivers, who imagined I was subjecting my daughter to some life-threatening peril given the perspective-enhanced size and perceived menace of the croc in the foreground.

5. Diver as Editorial Illustration

Panduan Kittiwake was sunk as an artificial reef off Grand Cayman’s Seven Mile Beach, and it has evolved, as shipwrecks are prone to do, gaining a cloak of colorful sponges and providing habitats for marine life.

It is no surprise, however, that some of the more fragile elements succumbed to the storms that have passed through the area since the ship slipped beneath the waves in January 2011. The mirror in a crew bathroom is now long gone, but for a while careful positioning and lighting could capture the diver and their reflection. This shot became an editorial vignette in the Kittiwake tale.

6. Diver Silhouette

Divers in the distance can serve as an element of composition and help block the sun in the shot. Most digital cameras have a hard time holding detail with the sun shining through the water. Being deeper helps, as it mutes the exposure differential between the sun and the surrounding water, but you can also use your model to block the most intense part of the sun ball and make the exposure easier to control.

That’s what Barbara and I did with this shot in the Solomon Islands. When reviewing the images later, I commented on how she was consistently in the right place relative to the sun. She told me she could see her reflection in my dome and positioned herself accordingly. I hadn’t learned that trick. Postdive discussions of what worked and what didn’t make for a better collaborative team.

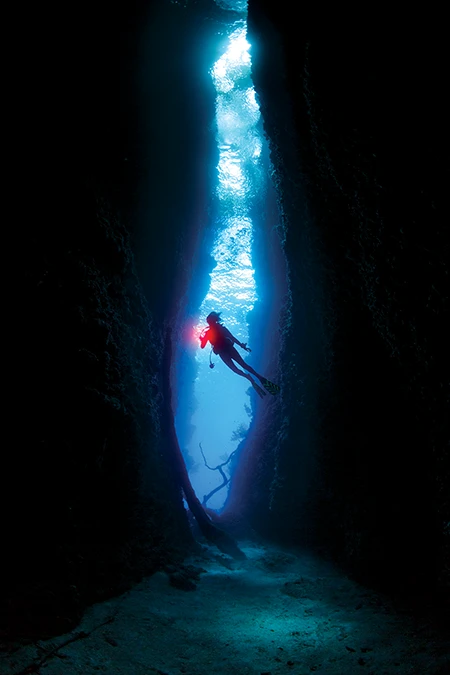

You can also separate the diver from some bit of wreck or reef at the same lateral depth, as with the photo of the diver swimming through the famed Leru Cut in the Solomons. In this case the diver using a dive light as a prop makes sense because she is entering a dark region of the reef, but I will also point out that the diver-with-light photo is used a bit excessively in dive magazines these days. If it’s a situation in which a diver might need a light — such as a cave, wreck, or night dive — then it is logical and adds to the composition.

7. Divers on Shipwrecks

Shipwrecks by themselves have photographic appeal but suffer from redundancy. The addition of a diver adds scale and human interest, making the sense of exploration relatable. You can position divers near a bit of the wreck, almost on the same plane of focus (like Maddie Cholnoky peering through a bit of wreckage on the Benwood in Key Largo), or they can position midwater in silhouette as well.

In the shot of the Aida wreck off Big Brother Island in the Red Sea, I wanted to be able to read the detail on the anthias and soft coral in the foreground, and the model would be an element of composition. The foreground was the primary plane of focus and where proximity to the strobe light would reveal the maximum color. Color from artificial light drifts off dramatically with subjects farther than 6 feet (1.8 meters) from the strobe. With a distant model silhouette the strobe contributes nothing toward illuminating the diver. Barbara was only about 10 feet (3 m) away, however, and the strobe could add enough detail to reveal eye contact and provide a hint of color.

I have made a point of identifying the models in these shots. We often talk about what camera or housing we used to take our underwater photos, but the models are more important. None of these images would have happened without the patient and skilled collaboration of underwater models — they are the stars of these shots. When I made that circular motion with my hand and held up my finger for “one more time,” they didn’t respond in kind with their middle finger thrust in exasperation. I appreciate that.

© Alert Diver – Q4 2025