The frogmen of World War II

MOST PEOPLE KNOW the historical significance of D-Day, the infamous day when Allied forces landed on the shores of western Europe on June 6, 1944.

Many have heard stories and even seen films of the brave men carrying rifles who fearlessly charged out of the gates of amphibious landing craft and onto the beaches of Normandy, France, running directly into an onslaught of enemy machine gun and mortar fire.

Few people, however, know the story of the men who went into these enemy waters before them. Armed with nothing but a mask, fins, and a knife, these divers were tasked with destroying the countless enemy obstacles entrenched in the shallows that would prevent Allied watercraft laden with infantry from ever reaching the sand.

One of those divers, George Morgan, was only 17 years old. Having graduated from the U.S. Navy’s experimental Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) program just days before, Morgan found himself thrust amid the chaos and churning ocean surf of Omaha Beach.

NATIONAL NAVY SEAL MUSEUM

The task at hand seemed impossible: Clear angled metal beams, steel tetrahedrons, and concrete posts from 16 predetermined landing zones. Some zones were longer than football fields. And because of tides, weather, and the Allied watercraft speeding in fast behind them, the UDT divers barely had a half-hour to complete their mission.

Completely defenseless and fully exposed to the enemy, Morgan and the other UDT divers with him scrambled amid the horrific landscape and gruesome carnage. They dodged endless incoming rounds and explosions as they deployed demolitions to clear the beach zones so their brothers in arms could attempt to land.

Thirteen of the 16 zones were successfully cleared. The infantrymen who survived the landing would go on to secure the beachhead and the first major victory of the Allied forces’ push into Europe.

Only 48 percent of the UDT divers at Omaha Beach that day survived the grisly invasion, and yet they still completed their impossible mission. There would be no rest for Morgan and his fellow divers, however. D-Day was just their introduction to the war. Immediately following the battle, they were shipped out to the Pacific to continue the fight.

“Everybody did what they had to do,” said Morgan, now 95, reflecting on the events of that day and the days that followed. After Normandy he saw direct combat in numerous major operations in the Pacific theater, from the sands of Iwo Jima to the deadly reefs of Okinawa and the dark jungles of Borneo.

NATIONAL ARCHIVE

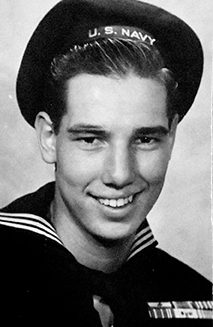

George Morgan in uniform, 1945

COURTESY GEORGE MORGAN

The combat application of the UDT in the war effort was both specific and dynamic. Conducting underwater reconnaissance was a major objective. The UDT divers went into enemy territory ahead of the main Allied amphibious landing forces, taking depth measurements and notating terrain features — vital information that often served as a determining factor in Allied watercrafts’ avenues of approach. They searched for enemy mines and underwater obstacles, destroying them with intricate explosives they expertly handled.

Scouting ahead to uncover enemy shoreline emplacements, the UDT divers were often the first to encounter enemy forces. In the rare instances when they discovered hostile-free environments, they would sometimes put up signs letting Allied forces know the UDT had been there first and that the area was safe for landing. While humorous at face value, the signs were well received.

The esprit de corps among the UDT divers, Marines, and Navy sailors was strong and built on mutual respect and care for one another. The UDT divers risked their lives to prepare a safe landing for ground forces, and they knew what those equally brave men would have to face once they landed on the shore.

The courage and tenacity of the demo divers

invites us to emulate the same principles in daily life.

Between waves of landing ground forces, UDT divers would volunteer to remove the dead bodies of Allied soldiers from the water by either retrieving them or weighing them down in impromptu burials at sea to keep the morale strong and not hamper the spirits of replacement soldiers when it was their turn to enter the fray. When Navy ships went down, UDT divers acted as rescue swimmers, retrieving wounded and injured sailors from the water and pulling them to safety.

Why are the incredible stories of UDT divers like Morgan unknown to most? During the course of World War II, the UDT’s commanding officer issued a media blackout. As prototype warriors in an emerging field, the utmost secrecy was necessary for the men to operate successfully.

After the war, the UDT divers evolved into what is known today as the U.S. Navy SEALs. These professed and proven “quiet professionals” still perform the same kinds of secretive missions as their UDT predecessors. The tradition of secrecy has kept the UDT’s exploits largely outside of the public’s awareness.

Andrew Dubbins, an award-winning journalist from Los Angeles, California, had the privilege of interviewing Morgan over an extended period in his journey to better understand the history of the UDT. “Morgan and his fellow frogmen came long before our modern age of high-tech warfare, exemplifying pure strength, endurance, resourcefulness, and courage,” Dubbins said. “The SEALs were able to draw from and build on the experiences and pioneering techniques of the World War II frogmen.”

A UDT diver conducts a demolition exercise under a ship’s keel.

NATIONAL NAVY SEAL MUSEUM

UDT divers truly were pioneers in their fieldcraft. Their training became even more innovative as a direct result of their experiences. In the icy waters of the Pacific, one UDT diver discovered that he could prevent his mask from fogging up by spitting into it. Wetsuits had yet to be invented, so demo divers like Morgan wore long johns thickly coated in grease over their swim trunks to provide insulation against the cold water.

Underwater demolition was particularly challenging work. Varying by design and mission specifications, a single UDT diver could sometimes be responsible for carrying up to 60 pounds (27 kilos) of explosives. The divers would give their best attempts at creating some level of neutral buoyancy to the waxed canvas bags that held the explosive material, but the bags were often too heavy or too inflated, making them extremely difficult to manage in the water.

The use of scuba did not have a practical combat application for the UDT. The brand-new regulator technology of the time, known as the Aqua-Lung, was still in its infancy. While the demo divers had some use for this device, it was not as dependable or as efficient as a well-trained skin diver. It also wasn’t readily available, and the UDT already had enough trouble trying to source rubber dive masks with tempered glass and swim fins with reinforced foot straps from the few U.S. sporting goods stores that carried them.

Both military and recreational divers today receive training about the safety hazards inherent to the activity before venturing off on their own. As the first divers of their kind, however, the UDT divers had no predecessors who could adequately warn them of the fundamental dangers they would face with diving. They commonly suffered from upper-respiratory and ear infections, painful muscle cramps, and hypothermia, all from overexposure to the cold water. They were not immune to painful encounters with marine life such as sharks and barracudas or abrasive contact with the toxins from coral reef polyps.

Barotraumas were common because UDT divers often had to execute rapid descents without proper equalization. Morgan surfaced after one dive with blood pouring out of his nose and ears after being unable to equalize and having to dive to depth regardless of the sinus pressure and pain he felt.

Even so, the innate dangers of diving were the least of their worries. As the war raged on, the threats and dangers to UDT divers increased. As the enemy quickly became aware of the UDT’s existence and purpose, they attacked them with vigor as the demo divers attempted to conduct their missions. Sniper and machine gun bullets whizzed over the heads of UDT divers at the surface. They hid from the incoming fire beneath the waves, holding their breath as long as they could and watching the bullets stop a few feet underwater and trickle down to them like fish food being dropped in an aquarium.

Staying underwater for protection was completely useless against enemy shells, which created huge shock waves when they exploded at depth. Any diver in proximity to a blast would suffer a concussion, incur damage to internal organs, or be killed outright. One particular shell explosion launched Morgan 20 feet (6 meters) in the air, rupturing a disk in his back, dislocating a limb, and lodging shrapnel in his body.

As the Navy drew closer to the Japanese homeland, the enemy dangers became unimaginable. Kamikaze fighter planes laden with explosives smashed themselves into the decks of Navy ships, and the UDT divers manned anti-aircraft quad guns in attempts to shoot them down.

The kamikaze planes had their own underwater counterparts: the human-operated small suicide submarines called Kaiten. The Japanese equivalent to the UDT, the fukuryu (dragon divers) swam underneath Navy ships and stabbed upward at the hulls with pole charges. Underwater combat was not a Hollywood screen spectacle for the UDT divers but a frightening reality that threatened the frogmen’s lives every day.

“Will I live to see the sunrise?” was an intrusive and inescapable question that lingered in Morgan’s mind. “You’re surrounded by death,” Morgan told Dubbins during one of their many talks. “My thinking all during the war, especially when we were overseas, was, is this going to be my last day, my last week? You don’t know.”

The story of the UDT holds value to anyone who has ever donned a mask and fins and swum beneath the ocean waves. The courage and tenacity of the demo divers invites us to emulate the same principles in daily life. It also provides a sense of gratitude, not just for the equipment that divers have at their disposal today but also for the world we are able to dive in thanks to the personal sacrifices of these divers.

“Morgan has said to me several times that he doesn’t enjoy rehashing these painful war stories and that he’s finding our conversations difficult. I told him that it’s important to share his story so that future generations never forget.” Dubbins said. “But I often wonder if I’m doing the right thing, probing an old man’s most difficult memories. Then again, if I don’t ask the questions now, they may never be answered.”

Read more about Morgan’s personal journey as a UDT diver and Dubbins’ experience writing about it in his new book, Into Enemy Waters. AD

JELAJAH LEBIH LANJUT

Learn more about UDT divers in these videos.

© Alert Diver — Q4 2022