To the delight of the divers staying at Tawali Resort on the shores of Milne Bay in Papua New Guinea, Anna’s hunch turns out to be right on track. Her premonition began with a late afternoon sighting of a sea star on its tiptoes exuding a long, lazy spiral of smokey spawn — a possible tip-off of coral spawning to come.

Soon after drying off, Anna made a few quick keystrokes and found what she was hoping for: The annual synchronized coral spawn on the Great Barrier Reef, not far to the south of us, would happen on the fourth evening after the full moon. Our timing is right. Four nights later, 20 of us made a dive we will never forget.

Between 7 p.m. and 8:30 p.m., multiple species from the ubiquitous genus Acropora — popularly known as staghorn, elkhorn, and plate-forming corals — launch their entire yearly reproductive payload. It is a single, eye-popping, synchronized mass spawning event cued by the moon phase, water temperature, and disparate factors conducive to a given region.

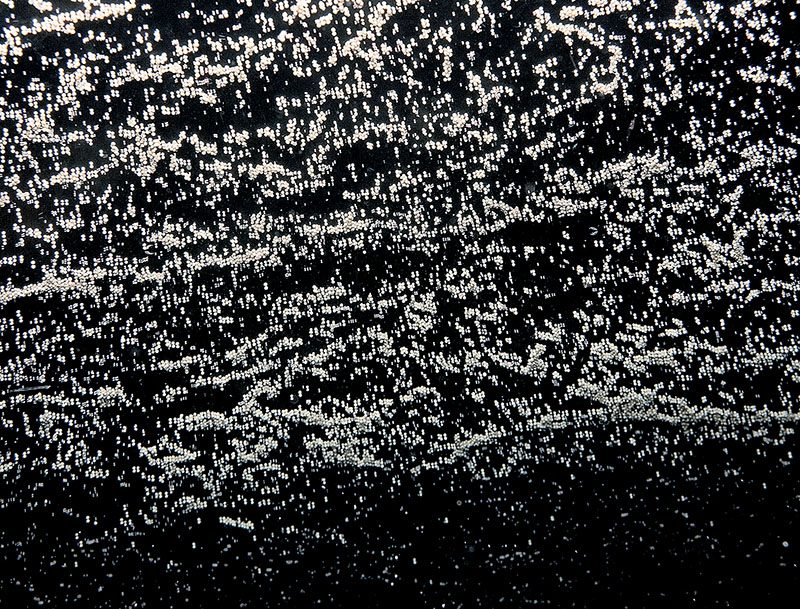

In an instant, the sea fills with hundreds, and then thousands, and then millions of BB-sized bundles. They are pinkish and plump, with eggs and sperm, rising inexorably toward the surface on a quest to replenish coral reefs near and far. Soon the multitudes coalesce above, forming a gleaming slick that extends as far as my hand light can reach.

On the ride back to the resort, our skiff of jubilant divers skims past slick after slick blanketing the bay’s wine-dark waters. The heroic sendoff of a new generation of corals into an environmentally uncertain world sends my mind wandering along with the specks of life.

As the rafts drift offshore, the bundles spill their gametes into a stewing brew of external fertilization. It’s all part of the sea’s grand strategy of synchronized broadcast spawning. This epic game plan provides stationary animals, such as reef-building stony corals and sponges, with high fertilization rates and an energy-efficient means of enhancing genetic diversity.

At the same time, the sheer flood of fat-filled food, which also includes the gametes of many mobile reef dwellers, overwhelms predators. While the top of the food chain is busy feasting, the lucky would-be prey can escape into the open sea, where fertilized embryos metamorphose into mobile larvae of many types. The corals’ version, known as planula larvae, are tiny, flattened, cilia-powered ovals packed with an inherent sense of destiny.

Many mysteries still surround the larvae’s eventual settlement onto stable, nearshore structures. The few survivors that make it back to the reef likely follow chemical clues exuded by members of their species, microbial microfilm, and crustose coralline algae — the calcifying glue of the reef.

Once settled, the wanderers wander no more. Within days they transform into sedentary, saclike polyps with feeding tentacles ringing their mouths. The polyps soon begin laying down cup-shaped calcium-carbonate skeletons known as corallites to protect their vulnerable bodies. With continued luck, the polyps asexually bud replicas of themselves that beget others until the growing colony matures sufficiently to add their gametes in the annual spawn. But not all is well for recent coral settlers.

After a two-year pandemic hiatus, Anna and I arrive in Bonaire to witness the fall’s annual coral spawn. It had been more than 50 years since I first dived at this southern Caribbean island. In those days, massive staghorn and elkhorn thickets paralleled the calm western shoreline for miles. Today the famed offshore slope of boulder, brain, and finger corals still plunges regally from the shallows to 100 feet (30 meters), but the historic inshore thickets are no more. A wide, barren shelf scattered with broken coral rubble jutting from the sand like old bones spreads in their place. The culprits: warming water, bleaching, pollution and associated diseases, elevated storm surge, overfishing, coastal construction — I’ll stop there.

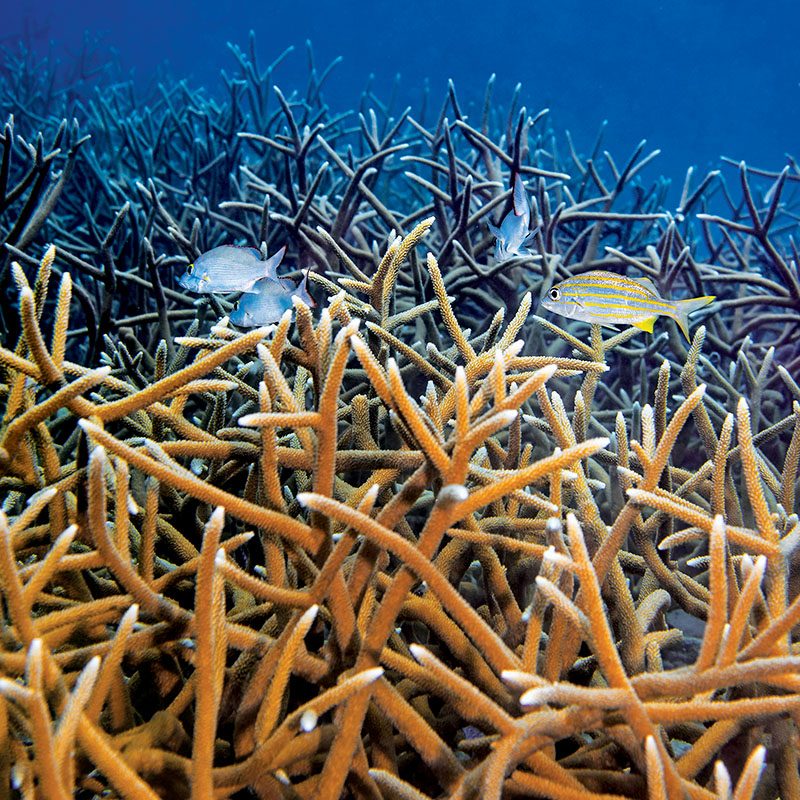

Some call the devastating loss across the entire region of complex natural habitat created by titanic tangles of Acropora branches the “flattening of the Caribbean.” These labyrinths of untold hiding places have sheltered a flourishing sea of little fishes for ages. But in four short decades, they are gone forever. Or are they?

Today, not a stone’s throw from the resort’s dock, a staghorn thicket spreads across 4,000 square feet (372 square meters) of previously bare sand. This oasis of hope, which scientists and volunteers patched together piece by piece in 2013 using branches cultivated in a nearby underwater nursery of PVC trees, triumphantly spawned en masse in 2018.

Having been present at the initial planting by volunteer divers from Reef Renewal Foundation Bonaire, Anna and I have taken the site’s evolution to heart. As on previous visits, we conduct a Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) fish survey on the revered patch. This year’s fish count ballooned to 32 species, and there was a notable increase in biomass inhabiting the dense thicket. Better yet, this restoration effort is far from the only one. With the combined force of the island’s dive operations, citizenry, legions of visitors, the National Parks Foundation of Bonaire, and the Dutch government, 41,000 pieces of coral nurtured in 11 nurseries have been laboriously outplanted on areas blanketing more than 100,000 square feet (9.290 square meters) of fallow sea floor, all in a short decade. Hurray for all of us!

© Alert Diver - Q1 2023