Scuba divers typically associate the term “squeeze” with a pressure-related injury (barotrauma) to the ears, sinuses, or eyes. In freediving, the term is commonly used to refer to a lung injury.

Many freedivers are familiar with the idea of a squeeze, but how and why this phenomenon occurs is not yet fully understood. In 2023, DAN partnered with University of California San Diego to survey breath-hold divers about their experiences with lung injury (“squeeze”) events and their return to freediving afterward. The study sought to identify trends in symptoms, possible causes, and recovery patterns — ultimately aiming to promote safer practices and clearer recommendations for managing a squeeze.

What Is Squeeze?

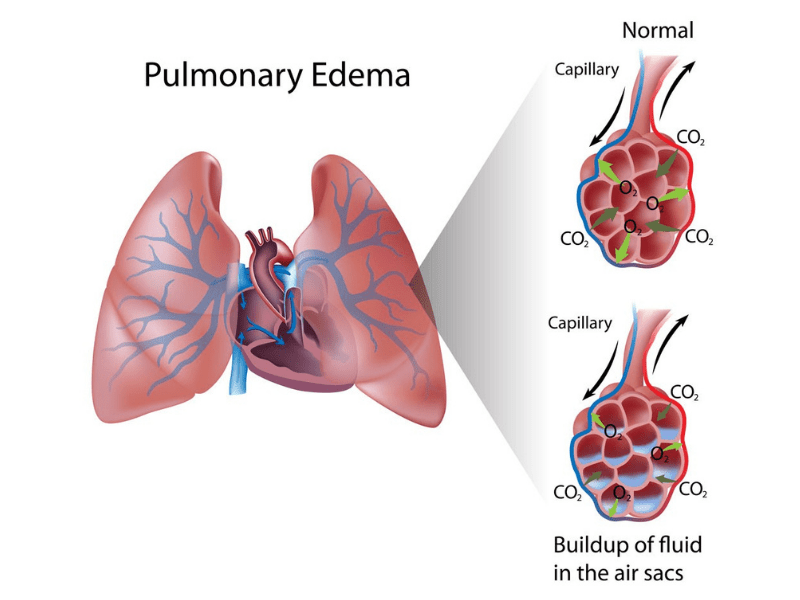

As a freediver descends, increasing water pressure compresses the lungs within the chest cavity. If this compression exceeds the body’s ability to compensate, it may cause stress or damage to the lung tissue, like small leaks or tears. This can result in pulmonary barotrauma or fluid accumulation (pulmonary edema) in the lungs, leading to symptoms such as coughing (with or without blood), chest tightness, shortness of breath, fatigue, or lightheadedness.

According to proceedings from the 2023 Barotrauma and SIPE in Freediving SCED/DAN Workshop, these symptoms fall under the umbrella of Freediving-Induced Pulmonary Syndrome (FIPS) — a term proposed to encompass the full spectrum of respiratory symptoms associated with breath-hold diving, particularly when the exact mechanism of injury is unclear or multifactorial. Suspected subtypes of FIPS include pulmonary edema, tracheal/laryngeal edema and/or hemorrhage, and alveolar barotrauma.

Researchers and dive medicine experts are continuing to refine this classification and explore treatment pathways.

The Survey

To better understand how breath-hold divers experience and recover from squeeze events, DAN launched a two-month online survey in 2023. A total of 132 divers responded — mostly recreational and competitive freedivers — with 98% holding a formal certification in their discipline. Of those, 96% reported having experienced at least one squeeze incident between 2008 and 2023, resulting in 140 total events assessed in this study. Many participants reported repeated incidents, with an average of 8 ± 20 squeeze events over the course of their diving history.

Respondents represented a wide range of breath-hold diving activities, including freediving, spearfishing, and underwater hockey. Among freediving disciplines, the top three most frequently associated with squeeze events were free immersion (FIM), constant weight with bifins (CWTB), and constant weight with monofin (CWT). FIM — which involves pulling oneself along a dive line and may create greater strain — accounted for the highest number of reported squeezes. Supporting this trend, 72% of incidents occurred during training dives, when divers were often pushing their limits or refining techniques.

Reported depths at which squeeze symptoms occurred ranged from 10 to 113 meters (32–370 feet), with an average depth of 43 ± 22 meters (141 ± 72 feet). Notably, most squeeze incidents occurred at depths shallower than the diver’s personal best, suggesting that depth alone does not explain injury risk. Instead, participant-reported causes, including movement at depth, diaphragm contractions, and insufficient warm-up, point toward dynamic strain and stressed chest movement playing a more influential role in the risk of a squeeze event.

Symptoms and Recovery

The most reported symptoms following a squeeze were coughing, mucus (sputum) production, and fatigue. While coughing up blood (hemoptysis) is often considered a hallmark sign of lung injury, many participants reported symptoms consistent with a squeeze without any visible blood, indicating a broader range of injury than sometimes recognized.

Most divers (80%) did not seek medical care or treatment, including oxygen administration, after experiencing a squeeze. Among the 36 individuals (26%) who sought medical attention, 14 were hospitalized, with diagnostic evaluations varying from blood tests to CT scans. This suggests that while most incidents may be mild and self-limiting, a subset of cases can be serious, requiring clinical care. However, the lack of consistent medical follow-up makes it difficult to evaluate whether long-term damage may go unnoticed in untreated cases.

Recommendations regarding return-to-dive time varied greatly from a few days to a full year, with average recommendations of one to two months. Despite these inconsistencies, on average, divers were able to return to the same depth that their squeeze occurred within three months of the incident.

Kesimpulan

This survey suggests that squeeze events are more common than previously recognized, often going unreported and untreated, and are highly individual in presentation and recovery. While many divers appear to recover capability, particularly in mild cases, the lack of medical oversight makes it difficult to assess long-term consequences.

More research is needed to establish consistent diagnostic criteria, treatment protocols, and return-to-dive guidelines. In the meantime, increasing awareness of the range of symptoms and potential risks may help breath-hold divers make more informed decisions about their training, warm-ups, and post-incident care. Full results from this study have been published in Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine.