Rethinking our relationship with sharks

Sharks are among the ocean’s oldest survivors. They have cruised through Earth’s seas for more than 450 million years — long before the first trees grew or Saturn formed its rings. They endured five mass extinction events that eliminated most life, including the dinosaurs, persisting when most other animals did not.

Now sharks face a new kind of threat: humans. Overfishing, habitat loss, climate change, and pollution are putting unprecedented pressure on shark populations worldwide. Each year humans kill an estimated 100 million sharks — nearly 274,000 per day or three every second.

We do not have a shark problem; we have a people problem. From the way we fish to the way we tell stories, humanity’s choices shape the fate of sharks more than any natural force.

Despite their endurance, sharks remain profoundly vulnerable — not only to environmental pressures but also to the ways humans perceive them. Our relationship with sharks has been a shifting mosaic of reverence, fear, fascination, and exploitation. For centuries cultures, fishers, artists, scientists, and now global tourism operators have shaped how we see sharks and how we treat them.

The story of sharks is as much about us as it is about them. To understand their future, we must examine the long arc of history and the choices we are making now.

Sacred Sharks: Early Cultural Connections

Long before Western sailors painted sharks as sea monsters, island cultures across the Pacific revered them. In Polynesia, sharks were not feared but honored as aumakua — ancestral guardians that embodied family spirits. These sharks were believed to protect their human kin, guiding them through storms, steering canoes, or warning of danger.

Oral traditions abound, with stories of shark gods that married mortals and protective sharks that rescued shipwrecked sailors, carrying them safely to shore. In Hawaiʻi, families offered prayers and gifts to shark aumakua, respecting them as kin. This reverence was not abstract — it was lived, practical, and rooted in an ethic of reciprocity. People took from the sea but also honored the beings who shared it.

This early cultural connection reveals a very different view of sharks: not as threats, but as powerful allies. It stands in stark contrast to the narrative that came to dominate Western thought.

Demonization in Early Western Art and Thought

The initial European encounters with sharks were colored by fear and unfamiliarity. One of the most famous early images is John Singleton Copley’s 1778 painting Watson and the Shark. It depicts a young man in Havana Harbor, Cuba, his body arched in terror as a shark swims toward him while rescuers try to help.

The image spread widely, searing the idea of sharks as merciless killers into the public imagination. The waters of Havana were teeming with trade, sewage, and human activity that attracted opportunistic predators, but nuance rarely survives in a work of art. Instead, sharks became the perfect canvas for projecting fear of the unknown, the wild, and the ocean itself.

From this period onward Western literature, travelogues, and sea tales often cast sharks as symbols of menace. The seeds of fear were planted long before Hollywood brought them to full bloom.

Sharks as Predators in the Public Record

Our fascination with shark danger grew into formal recordkeeping. The International Shark Attack File, the world’s longest-running database of shark–human encounters, traces incidents back more than 400 years. Its purpose has always been to gather objective data: the number of incidents, under what circumstances, and the species involved.

The numbers tell a striking story: Fatal shark attacks are rare. There are only about four human fatalities from shark attacks globally every year — which is far fewer than deaths by lightning, boating accidents, dogs, cows, or even falling coconuts — yet these encounters loom large in our psyche.

Psychologists note that humans are primed to fear unseen predators, especially in an environment where we feel out of place. The mere possibility of a lurking shark is enough to shape behavior, keeping many people out of the water entirely.

The data remind us of a truth some people struggle to accept: Sharks are not the relentless hunters of legend. They are predators, yes, but also vital to maintaining ocean health and biodiversity. Interactions with humans are mostly accidental.

The Jaws Effect

In the summer of 1975, one movie changed everything. Les dents de la mer didn’t just entertain — it terrified. Steven Spielberg’s film, based on Peter Benchley’s novel, turned a great white shark into the perfect villain: silent, relentless, and waiting just offshore. It struck a primal chord, making the ocean seem dangerous. Audiences feared not only sharks but also the sea.

The impact was immediate and devastating. Almost overnight, shark fishing tournaments surged, culling programs were justified, and sharks were slaughtered as trophies. For five decades the legacy of Les dents de la mer distorted public perception, severing the emotional connection between people and the ocean. Many people who might have been drawn to the water instead stayed away, haunted by images of dorsal fins and ominous music.

The Discovery Channel’s Shark Week, launched in 1988, capitalized on that fear, often with sensationalist titles such as Sharkpocalypse et du Great White Serial Killer. Fear became entertainment, and entertainment became a form of cultural reinforcement.

Sharks vs. Fishers: The Depredation Debate

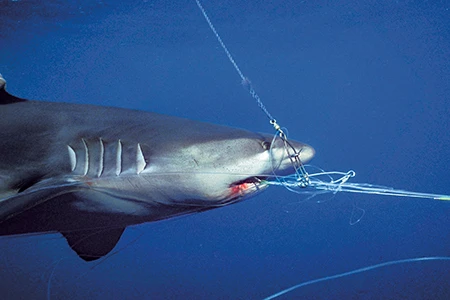

Not all shark–human conflicts happen at the beach. Increasingly, they unfold on fishing lines. Anglers in Florida and beyond face a growing challenge: sharks snatching hooked fish before fishers can reel in the catch. This behavior, known as depredation, is not new, but reports are increasing as shark populations begin to recover.

Depredation is maddening for fishers, who are frustrated when only half a fish comes aboard after hours of effort and investments in costly gear. Some fishers see sharks as nuisances, claiming there are too many in the water, but this view is distorted from a scientific perspective. Many shark populations were driven to historic lows in the 20th century. What might seem like a population explosion more recently is actually the ocean’s predators returning to something closer to their natural abundance levels.

This conflict has now reached the U.S. Congress. In 2025 lawmakers introduced the Supporting the Health of Aquatic systems through Research, Knowledge, and Enhanced Dialogue (SHARKED) Act to address depredation. The bill proposes establishing a federal task force to bring together scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), representatives of state agencies, fishery managers, and independent experts to study the issue. The group’s priorities would include shark behavior, nonlethal deterrents, angler education, and the ecological role of sharks.

Supporters view the proposed legislation (H.R.207) as an opportunity for science-driven solutions. Conservationists caution that vague language could leave room for lethal measures, which would be a dangerous prospect for species that are still rebuilding. The challenge will be to ensure that the legislation channels frustration into innovation, not culling. The U.S. House of Representatives has passed the bill, and the U.S. Senate has referred it to the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

Depredation is more than a nuisance — it is a reminder of the complex ways human activity reshapes predator–prey dynamics. The SHARKED Act could set a precedent for whether we will treat sharks as competitors to be managed or as ocean residents whose presence demands that we adapt to their needs.

Sharks in the Media: Monetizing the Monster

As policymakers wrestle with conflicts between sharks and fishers, media narratives continue to sway public opinion. Shark Week and similar programming generate millions in annual revenue. Fear sells, and the lure of “killer shark” headlines remains strong.

Yet a shift is underway. Viewers are increasingly drawn to documentaries that highlight shark science, conservation, and the thrill of safely encountering these animals. Programs that replace sensationalism with education may finally be rewriting the script. The stakes are high: The stories told on our screens help determine whether the next generation fears sharks or fights to protect them.

Sharks as an Economic Asset

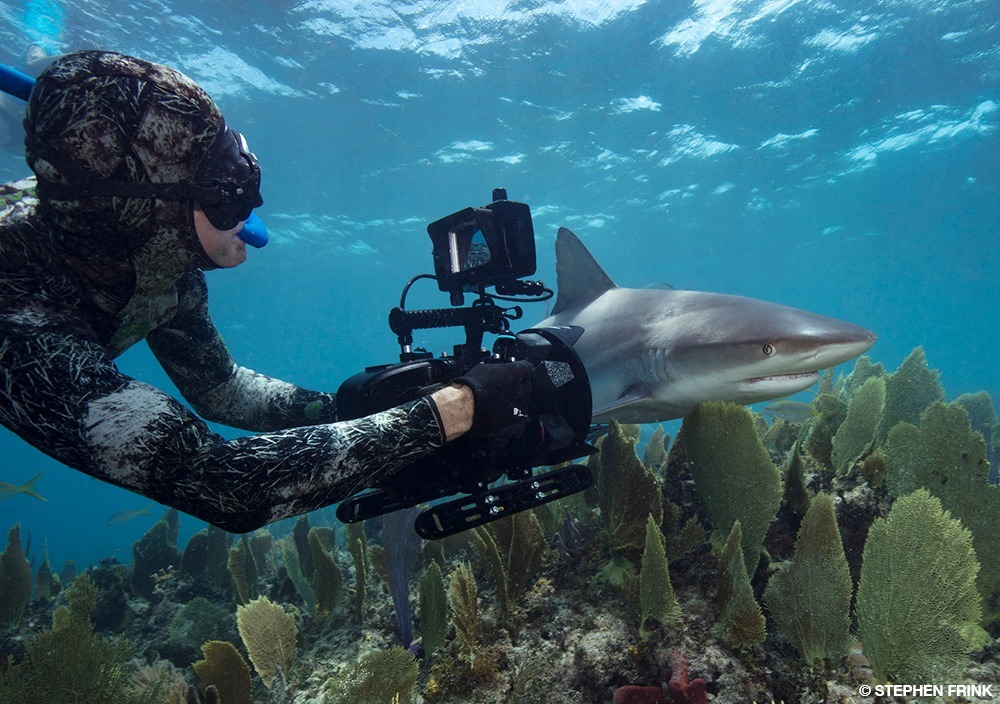

If the media profits from fear, many nations profit from fascination. Shark diving is big business in the Bahamas, Fiji, Palau, and beyond. Tourists spend millions to see reef sharks, tiger sharks, bull sharks, hammerheads, and whale sharks in the wild. Studies show that a single shark, alive and thriving, can generate more than a million dollars in tourism revenue over its lifetime — far more than its value as a one-time catch.

But the presence of sharks brings risk. On the rare occasions that incidents occur with divers, they are often magnified in headlines despite these events being exceedingly uncommon compared with the thousands of successful shark dives conducted worldwide each year. With proper training, knowledge of shark behavior, and strict safety protocols, operators minimize risks for both people and sharks.

Shark tourism not only creates revenue but also builds local stewardship. When communities view sharks as a source of sustainable income, they have powerful incentives to protect them and their habitats. In many cases ecotourism has turned former shark hunters into shark guardians.

The Bahamasis one of the strongest examples. The country established a national shark sanctuary in 2011, banning commercial shark fishing across its waters. Shark diving now contributes more than$100 million annually to the Bahamian economy, with thriving populations of reef sharks, tiger sharks, and hammerheads drawing divers from around the globe.

Palauwent even further. In 2009 this Pacific Island nation created the world’s first shark sanctuary, protecting sharks across its entire Exclusive Economic Zone, encompassing more than 230,000 square miles (595,697 square kilometers) of ocean. The sanctuary not only safeguarded Palau’s reef sharks but also became a magnet for dive tourism, which now represents a major share of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Fuvahmulah, a remote island in the Maldives, offers another inspiring model. Their waters are known as one of the world’s premier tiger shark diving destinations, hosting dense and consistent gatherings of these apex predators year-round, making it a diver magnet. Sightings of 20 or more tiger sharks during a single dive are not uncommon.

As a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Fuvahmulah has leveraged scientific curiosity and tourism by securing protections under the Maldives’ national shark sanctuary and defining and implementing stringent dive regulations. Researchers have discovered that many of the tiger sharks are pregnant and use the island’s waters as breeding or nursery grounds.

These examples demonstrate ecotourism’s dual benefits: protecting sharks while empowering local communities. The Bahamas, Palau, and Fuvahmulah prove that when sharks are allowed to thrive, both people and nature prosper.

Rewriting the Shark Narrative

From Polynesian aumakua to Les dents de la mer, from debates over depredation to the rise of dive tourism, sharks have been portrayed as gods, monsters, and nuisances. Yet the truth is far simpler and more profound: Sharks are keystone predators that keep oceans healthy.

The future of sharks — and our relationship with them — depends on the choices we make now. The SHARKED Act highlights the challenges of coexistence, while places like the Bahamas, Palau, and Fuvahmulah show what is possible when sharks are protected. In these places sharks have shifted from being hunted to being celebrated. They now fuel local economies, inspire global divers, and, in Fuvahmulah’s case, even provide insight into the reproductive mysteries of tiger sharks.

Peter Benchley, the author of Les dents de la mer, came to regret the monster he created on the page. He spent his later years as a fierce advocate for shark conservation, often saying he would never have written the book the same way had he known the truth. His change of heart reminds us that stories can wound, but they can also heal.

It is time to tell a new story about sharks: not one of fear, but of fascination, respect, and stewardship. If we can rewrite the narrative, we can ensure that sharks continue to roam our seas as living guardians of the ocean’s future.

En savoir plus

Find more about Beneath the Fin in this bonus photo gallery.

© Alert Diver – Q4 2025