Shore diving Monterey Bay and (slightly) beyond

Our departure date has finally arrived. As the engine comes to life, I try to settle in for the long haul, knowing it will be many hours before we arrive at our destination. Moments later we’re underway, and I let my eyelids close briefly, willing the strain of the past six months to dissipate. An instant later, the near silence is broken by a voice asking, “How about something to drink?”

Under normal circumstances I’d smile gratefully at the flight attendant and ask for water or — full disclosure here — champagne. But this is 2020, and “normal” has been turned upside down. I open my eyes, sigh and grab a can out of the cooler next to me, popping the top before I pass it to Andy, who’s maneuvering us down the highway in a rented SUV filled to the brim with tanks, dive gear and camera equipment.

A podcast instead of a new-release movie, a can of sparkling water instead of a glass of sparkling wine, fabric face masks instead of a sleep mask, and a driver’s license in my pocket instead of a passport make this dive trip strikingly different from nearly every other we’ve taken. With a global pandemic limiting our travel options, we’ve had to adapt. No hotels, restaurant meals or luxury boat dives with a boisterous group await us at the end of our voyage.

It’s not as big of a sacrifice as it might seem. Our small rental home comes stocked with groceries, and our destination, Central California, boasts some of the best shore diving in the U.S. I allow myself to feel an indulgent thrill of excitement — a bit of a splurge during this odd year — as we settle in for the drive. Next stop: Morro Bay.

Getting There Is Half the Fun

We’ve just started our adventure, and we’re already rushing. The North T-Pier in Morro Bay is renowned for incredible macro subjects, but the diving in this area is very tide-dependent. The best visibility is at high tide, and the sometimes-extreme currents necessitate hitting the water at slack, so in-the-know divers generally limit themselves to one of usually only two fleeting daily opportunities to explore here.

We’ve arrived just in time for a brief diving window. We check in quickly with the harbormaster and Coast Guard, conveniently located on the pier, and gear up. The entry here is simple, with a ramp in front of the harbormaster’s office leading to a floating dock from which we can stride into the water. Staying under the structure as much as possible to avoid the boat traffic, we swim gingerly until we reach a suitable spot and start our drop into 20-ish feet of green murk. I’m immediately thankful that we opted for peak high tide, because if this is the visibility at its best, then I wouldn’t want to see its worst.

We’re laughing as we descend until the bottom comes into view, and holy cow: Nudibranchs are everywhere. I may be able to see only 10 feet in front of me, but that’s plenty to appreciate this bounty. We get busy with our cameras, and by the time I can feel the insistent movement of the outgoing tide, I’ve photographed 12 different slug species.

Exiting the water here is quite a bit less graceful than entering. With a little cooperation on our climb up the rocks, we make it back to our car with limbs, gear and enthusiasm intact.

From Morro Bay, we weave our way up the coast, with the twists and turns of Highway 1 carrying us toward the towering bluffs of Big Sur. The cliffs mean there aren’t many well-known shore dives in this area. The one notable exception is Jade Cove. The challenging entry requires us to carry our gear from the highway to the beach, using a small trail that is sometimes steep and rocky. Although the dive site is lovely, you might wonder if it’s worth the trouble until you realize that most people who come here aren’t looking for pretty fish; they’re hunting for treasure. Visitors are allowed to collect jade from areas below the high-tide mark, an endeavor that’s addictive and sometimes rewarding. I’ve heard of divers uncovering huge chunks of the glossy, green mineral here.

We’ve been watching the building surf during our drive, so we’re not surprised when we pull over near the adjacent campground at Plaskett Creek and open the car door to be greeted by the roar of huge waves hitting the beach below. After we make our way to the path that leads down to the shoreline, we immediately confirm that we won’t be doing any underwater jade searches today — not safely, anyway. It’s disappointing, but recognizing when not to dive is one of the most important shore-diving lessons.

Bays of (Protected) Plenty

A marine forecast site confirms that we’re in for a few more days of large swell, so we head north toward the excellent and very protected dive sites at Carmel and Monterey Bay. Our first stop is Point Lobos State Marine Reserve, which contains some of our favorite dive sites in California. The boat ramp at Whaler’s Covemakes shore entries a breeze. Although it’s possible to explore the cove, we opt for a hearty surface swim that takes us outside of the cove, where the visibility is usually better. From there, we drop to about 60 feet to begin our exploration.

Urchins have recently affected the giant kelp at the mouth of the cove, so we head a bit deeper to revel in the Corynactis, sponges and flowerlike fish-eating anemones that cover the rocks, stopping to admire a grumpy lingcod resting atop a blunted pinnacle. The swell outside of the cove forms a strong surge that swings us widely back and forth. It’s fun except when we try to take a picture of the lingcod, who is not impressed with our uncoordinated efforts. The water motion has increased our normal air consumption, so we navigate back into Whaler’s Cove, where a harbor seal stalks Andy, and I excitedly photograph a monkeyface eel peeping out from under a rock.

There are plenty of protected sites to visit as we move north, though we have to bypass Monastery Beach for now. North Monastery, with its anemone-dotted boulders and giant kelp,is one of the best dives in the area, but the beach here is so steep that the entry can be treacherous when the surf is up. We opt instead to dive some of the sites alongside Cannery Row in Monterey, starting with McAbee Beach. After scoring a spot next to the beach access point, we gear up and walk across the rubbly sand and into the water, slightly angling north as we swim toward a bit of kelp visible at the surface. We descend to 35 feet and navigate to head a bit deeper, aiming for an area where clusters of giant plumose anemones begin to appear on the rocky reef. As we’re puttering along, a small tussle on a nearby rock catches our attention. We’ve stumbled upon a nesting cabezon fiercely protecting an egg clutch from a small group of hungry rockfish — a fantastic marine life find that occupies the rest of our dive day.

The next day we dive Metridium Fields, another nearby shore-access site also known for giant plumose anemones. From the adjacent San Carlos Beach parking lot, we gear up and pick our way around the occasional rocks in the shallow water, doing our best to keep our feet planted on the sand until we’re deep enough to descend. We follow a large, invertebrate-encrusted pipe that extends from an old pump house until it ends and then head due north, knowing we’ll hit rocks covered with plumose anemones and tons of other marine life within minutes.

As we begin our swim, we spot a few sea nettle jellyfish, but as the ocean floor drops to 40 and then 50 feet, the water color shifts from light blue-green to dark green and planktony. As I prepare to photograph a small cluster of anemones, I notice that the water is now filled with sea nettle jellyfish — so many that they block much of the ambient light. Sudden blooms like this can happen during tidal shifts, but I’ve never seen anything this abrupt before, and it seems as if there are more jellyfish in the water every time I look up. When we turn our dive, I resign myself to the inevitability of a few unpleasant minutes. Sea nettles are gorgeous, but their tentacles can pack a painful wallop; with so many of them here, there’s no chance we can avoid getting stung. I pull my hood tight, put my camera in front of my face and embrace the moment, thankful that I have some topical sting relief in the car.

On the other side of the San Carlos Beach parking lot is the Breakwater, Monterey’s best-known dive site. Divers from all over Central California get certified here and return again and again. This familiar site is protected and nearly always accessible, and the marine life here is consistently outstanding. The cross section of divers in the parking lot is a testament to the site’s popularity. I chat briefly with a 79-year-old woman pulling on a drysuit. Behind us, a dad is helping his preteen son lift a small tank onto his back while he asks us about our camera systems.

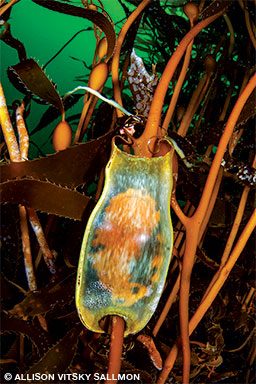

We’ve allotted a few days to explore the various aspects of this site. First, we swim straight out from the beach to photograph large Dendronotus iris nudibranchs gorging on tube anemones. A long swim toward the end of the wall reveals a rookery of California sea lions performing complex acrobatics and barking obnoxiously at us as they twist in the water column. We spend most of our time diving the kelpy, rocky reef that abuts the break wall, where cabezon and lingcod rest on the reef, shark egg cases may be hidden in the holdfasts and the luckiest divers may spot a hunting otter or cormorant.

Whale of an Appetite

Topside days are a tough sell for us when we’re on a dive trip, but we always make an exception in Monterey to visit nearby Big Sur. After days of nonstop shore diving and cold water, we’re ready for a break. Our nondiving day is the only one we spend on a boat — a whale-watching boat, to be precise. In the late summer and early fall, huge baitfish schools gather in the nutrient-rich waters of Monterey Bay and attract predators such as sea lions, birds, sharks and whales, especially humpbacks. The whale action is generally proportional to the fish action, so some years are better than others. We’ve heard that this year is off the scale. With safety and distancing in mind, we’ve splurged and booked a private charter on a spacious boat with one other couple, a pair of veteran local photographers who’ve plied me with whale photos and tales of incredible, National Geographic-worthy activity.

I’ve been on very few whale-watching tours and none for the primary goal of viewing humpbacks. When the time comes for decision-making and money-spending, I always go for diving over topside pursuits, because I prefer being underwater to anywhere else. After the first few hours on this tour, during which I’ve watched nothing but a distant whale fluke and a dismissive pod of dolphins, I feel smug about my preferences. The captain tells us that a small boat has reported another whale close to the harbor, and we’ll check it out on the way back (code for “we’re turning around”). Disappointment settles over me, and I admit that it dissipates only a bit when the new whale, identified as a calf from the previous season, comes into view. There’s some feeding going on, but he’s not emerging much from the ocean’s surface, and it’s tough to see — much less photograph — the action. The view is undeniably amazing, but in my head a part of me is stomping her petulant foot and saying, “This is not the spectacular action I was promised!”

It’s a good thing I keep those disagreeable thoughts locked in my head, because minutes later we spot a wake in the distance. “Incoming!” shouts the captain. “More whales, and they’re coming in hot!” The approaching beasts submerge, leaving our small group craning our heads to locate them, and then we hear a splash as three massive whales launch themselves skyward in synchrony, their barnacled jaws snapping as streams of anchovy-filled water drip down their faces. Without a single guilty thought for the original young whale, who has been summarily kicked out of the buffet, and the unfortunate anchovy school that has officially become reclassified as dinner, we all let out a roar of excitement and grab our cameras. Again and again, the whales, experienced hunting partners, rise together from the ocean, allowing me to witness one of nature’s great spectacles from every topside angle. Hours later, when the sun has begun to set and my arms are shaky from hoisting a heavy camera lens, I have adjusted my attitude toward whale watching as we head back to the harbor.

End As You Begin

We’re under another pier, Monterey’s Municipal Wharf II (better known as Wharf II), for our last dive. After the fabulous marine life we witnessed under Morro Bay’s T-Pier, we couldn’t be more eager. We’re less concerned about tides and currents here, so we take our time gearing up. Entering the water is easy as we stride in smoothly from the adjacent beach, and the surf — apparently clued into our imminent departure — is finally flat as a pancake. This area is popular with fishers, so we do our best to stay under the structure as much as possible, watching closely for boat traffic and monofilament.

When we reach a curve in the pier, we descend to about 20 feet and don’t budge far from the drop point. Lacy, red bryozoans cover the structure at this curve that serves as a condominium complex for nudibranchs, fringehead blennies and shrimp. Only after several hours, when we are so cold that it becomes distracting, do we head back to shore.

As we remove our gear and place our tanks in the SUV, admiring the impressive stack of empty cylinders we’ve amassed, I feel a surge of happiness about the time we spent in the ocean, however unusual the details and restricted the approach. I realize I’m laughing for what seems like the first time in months. When I climb into the front seat for the long drive home, I immediately settle in, more relaxed than I would have thought possible during this year and, more important, ready to face the next few months. Next stop: home.

Shore Diving

Expert opinions: Divers familiar with the local shore-diving sites are a valuable source of information, including details on parking, optimal entry and exit sites, navigation, tides, currents, boat traffic, local regulations, recent conditions and marine life. Social media and local dive shops are excellent places to start.

Not diving: Knowing when not to dive is one of the most critical aspects of shore diving. Large surf or steep rocks can thwart even the most experienced shore divers, and extreme tidal shifts or currents can turn a relaxing dive into a stressful or dangerous experience with little or no warning.

Gearing up: Booties or drysuit boots with thick soles will allow you to comfortably get to your entry site, no matter how rugged the terrain. This approach often means using open-heel fins, in which case spring straps are a fantastic way to quickly get in and out of your fins. A signaling device and a line cutter are highly recommended. Appropriately clip lights or cameras to your buoyancy compensator so you can enter with your hands free; if you’re new to shore diving or are facing a very challenging entry, consider leaving behind your camera. Make a plan for where to put your car key, and then make a backup plan if you lose it. (Trust me on this; I speak from experience.) Make the extra effort to keep your gear clean. It’s a good idea to get dressed on a mat or tarp to minimize contact with sand or rocks, and it’s important to meticulously wash your gear after your dive.

Fitness facts: Although some shore-diving sites allow you to stroll 10 feet to the water’s edge, enter with no surf and descend almost immediately, far more of them require additional effort, such as navigating stairs, entering through the surf or completing a surface swim. Be sure to physically prepare for the anticipated exertion.

Cara Menyelam

Conditions and skill level: Water temperatures in Central California range from 45°F to 60°F. Visibility varies from less than 10 feet to more than 70 feet. Plan to use a drysuit or a good-quality 7 mm wetsuit with a hood and gloves. Monterey and Carmel bays offer a range of appropriate sites for all skill levels, though visitors lacking coldwater diving experience should consider hiring a dive guide.

Reservations: Carmel and Monterey bays contain a complex system of marine protected areas. Divers of all levels should visit Point Lobos State Marine Reserve. Buddy teams should make reservations ahead of time, especially if you want to dive on weekends or holidays. Visit pointlobos.org for more information.

Surface interval: A coastal drive through Big Sur is a must-do, as is a visit to the elephant seal colony in San Simeon (about 100 miles south of Monterey), especially during the winter months when large males gather to compete for mates. The town of Monterey features a fantastic aquarium and the historical charm of Cannery Row. Whale watching is a common activity in the Monterey Bay area, especially in the late summer and fall. Topside shark tours to look for great whites from spring through fall have recently become popular.

Jelajahi Lebih Lanjut

See more of Andy and Allison Salmon’s images in a galeri foto bonus, and watch a video of divers exploring La Paz.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2021