Most divers know their scuba cylinders need a visual inspection every year and a hydrostatic test every five years (referred to as a requalification or a hydro). The actual regulations for cylinders and other dive equipment, however, are less clear.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies oxygen as a drug when provided to an injured or ill person. It requires specific labeling and product controls and must be individually prescribed to someone suffering from an ailment. When used incorrectly, oxygen can cause damage to someone’s health.

DAN’s vision is to make every dive incident- and accident-free. Improvements in training, equipment, operations, dive boats, and dive computers have made diving significantly safer. The safety of a dive, however, relies heavily on the diver’s practices.

Diving has inherent risks. The human body was not designed to be underwater, and drowning, decompression illness, barotrauma, hazardous marine life injuries, and preexisting health issues all require an emergency response. Diving in remote areas introduces additional risks, especially access to medical care.

There is a magic art to keeping divers’ attention long enough to impart safety-critical information. Talking about the cool things you will see is easy, but briefings also contain vital information that will keep your divers safe.

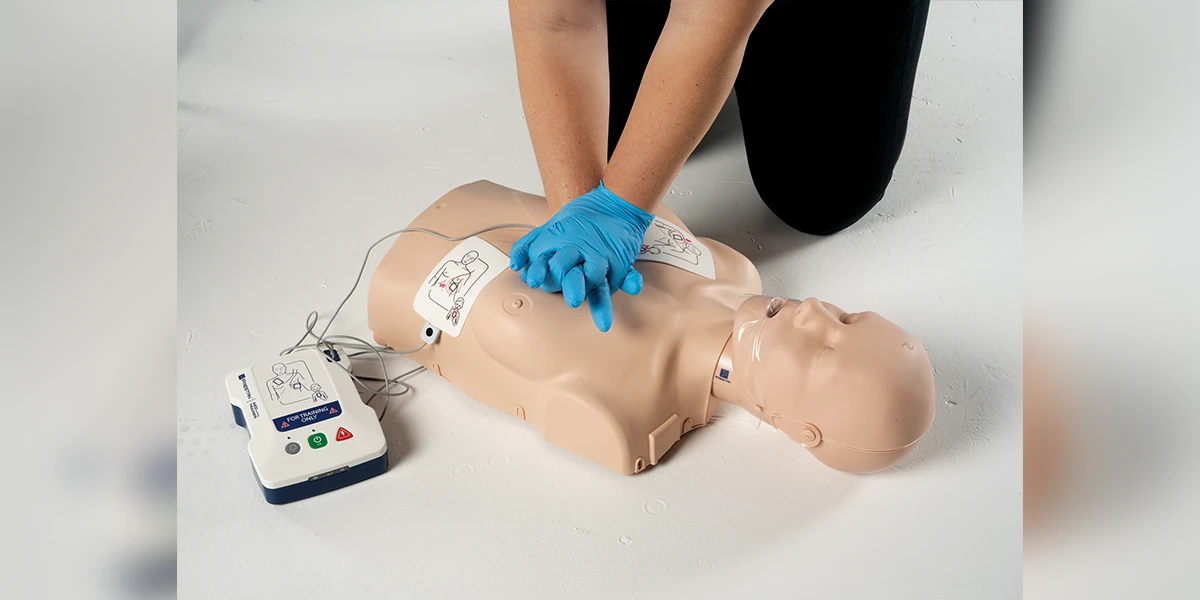

The automated external defibrillator (AED) was developed as a portable medical device and released for public use in the 1960s. The operation of AEDs has gotten simpler over the years, and the devices are now widely available for use by lay providers with basic training.

Cardiac arrest is a leading cause of death across the world, particularly in out-of-hospital settings, where timely recognition and response are critical to survival.