BERBAGI RUANG DENGAN HEWAN LIAR di alam adalah salah satu anugerah terbesar yang ditawarkan oleh kehidupan. Mungkin Anda pernah bertatapan langsung dengan orang utan di Kalimantan, atau mungkin Anda pernah melihat ikan badut dengan lembut merawat telurnya di terumbu karang. Anda mungkin pernah memergoki pasukan semut pemotong daun yang sedang mengangkut potongan tanaman kembali ke koloninya, atau mengintip dari balik haluan kapal hanya untuk melihat lumba-lumba.

Tidak peduli ukuran makhluk yang Anda temui atau kelangkaan spesiesnya, setiap kesempatan untuk membuka jendela ke dalam keberadaan sesama penghuni bumi ini adalah sebuah keistimewaan.

Lingkungan bawah air memperkuat keistimewaan tersebut. Sebagai mamalia darat, kita membutuhkan sedikit bantuan untuk bertahan hidup di dalam air, bahkan untuk waktu yang relatif singkat. Hambatan ini sangat mengurangi jumlah interaksi dekat yang dilakukan manusia dengan satwa laut, membuat setiap pertemuan menjadi lebih bermakna. Pertemuan dengan mamalia laut membuat fenomena tersebut menjadi sangat nyata karena kemungkinan untuk berbagi momen di bawah air dengan makhluk laut ini sangat rendah.

Paus biru sangat pemalu dan sepenuhnya fokus pada migrasi mereka. Untuk mengabadikan foto closeup yang intim ini, sang fotografer duduk di atas kayak selama berjam-jam di lepas pantai San Diego, California, hingga ia bisa mendekati paus biru. Dia kemudian meletakkan kameranya di dalam air dan secara membabi buta menangkap gambar yang sudah dia bayangkan. © AMOS NACHOUM

Berada di hadapan paus biru mungkin merupakan salah satu pengalaman yang paling menyentuh hati di Bumi, dan sangat beruntung memiliki kamera untuk mengabadikan momen tersebut adalah definisi tak ternilai harganya.

Paus biru (Balaenoptera musculus) bukan hanya hewan terbesar yang hidup saat ini, tapi juga hewan terbesar yang pernah hidup di Bumi. Kita sangat beruntung bisa hidup di masa yang sama dengan raksasa samudra ini.

Sulit untuk membayangkan betapa besarnya paus ini sampai Anda berada di dalam air bersama mereka. Beratnya bisa mencapai 200 ton dan biasanya tumbuh sepanjang 80 hingga 90 kaki. Sebuah studi tahun 2021 oleh Universitas Stanford menunjukkan bahwa dalam satu hari paus biru dewasa dapat mengonsumsi antara 10 hingga 20 ton plankton, dan krill adalah sumber makanan utama mereka.

Diklasifikasikan sebagai rorqual - kelompok paus balin terbesar - paus ini memiliki mulut besar yang dipenuhi hingga 400 lempeng balin, yang digunakan untuk menyaring plankton dari air laut. Mereka makan dengan meneguk air dalam jumlah besar yang mengandung krill ke dalam mulut mereka dan kemudian memaksa air keluar sementara plankton tetap terperangkap di dalam balin.

Paus biru mendiami semua lautan di dunia kecuali Arktik, dan sebagian besar melakukan migrasi monumental ke arah kutub pada musim panas dan khatulistiwa pada musim dingin. Mereka dapat menghasilkan suara keras dan berfrekuensi rendah yang memungkinkan mereka untuk berkomunikasi satu sama lain dalam jarak yang sangat jauh. Panggilan mereka dapat mencapai 188 desibel - lebih keras dari mesin jet - dan dapat menjangkau jarak hingga 1.000 mil.

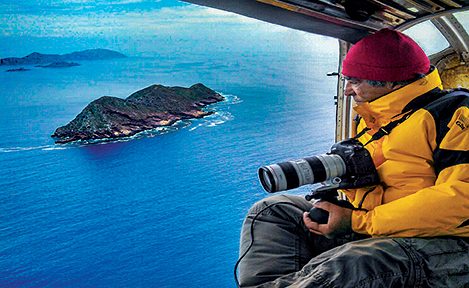

Amos Nachoum melakukan penerbangan pengintaian di atas Pulau Coronado, California, untuk mengidentifikasi paus yang bermigrasi ke utara dari Meksiko.

Rentang hidup rata-rata mereka adalah antara 80 dan 90 tahun, tetapi paus biru tertua yang tercatat diperkirakan berusia 110 tahun. Paus biru merupakan salah satu hewan yang hidup paling lama di bumi dan memiliki tingkat reproduksi yang rendah. Mereka mencapai kematangan seksual antara usia 5 dan 15 tahun, dan betina melahirkan seekor anak paus setiap dua hingga tiga tahun sekali setelah masa kehamilan sekitar satu tahun. Anak sapi dapat memiliki berat hingga 3 ton dan panjangnya hampir 25 kaki saat lahir.

Karena gaya hidup mereka yang sangat bermigrasi, melacak mereka dan mendapatkan perkiraan yang akurat tentang populasi mereka adalah hal yang sulit. Populasi paus biru saat ini diperkirakan berjumlah 10.000 hingga 25.000 ekor di seluruh dunia. Daftar Merah Persatuan Internasional untuk Konservasi Alam (IUCN) mengklasifikasikan mereka sebagai terancam punah, sebuah sebutan yang dihasilkan dari eksploitasi brutal selama seabad untuk mendapatkan minyak mereka. Populasi historis paus biru hampir punah pada pertengahan abad ke-20, tetapi mereka akhirnya dilindungi dari perburuan paus komersial pada tahun 1966 oleh Komisi Penangkapan Ikan Paus Internasional, yang menempatkan moratorium pada praktik tersebut 20 tahun kemudian.

Pada awal abad ke-20, terdapat lebih dari 300.000 paus biru. Perburuan paus komersial memusnahkan populasi tersebut, dan hanya sekitar

Masih tersisa 17.000 hari ini. © AMOS NACHOUM

Pemulihan merupakan proses yang lambat, tetapi kami melihat adanya kemajuan. Dengan adanya peraturan dan regulasi yang penting, jumlah paus biru di seluruh dunia kini mencapai 3 persen hingga 11 persen dari populasi historisnya. Mereka berangsur-angsur pulih, dan banyak praktik manajemen dan peraturan penangkapan ikan sekarang sepenuhnya melindungi mereka, tetapi mempromosikan perlindungan dan konservasi lebih lanjut dari raksasa biru ini sangat penting.

Sayangnya, lautan memiliki lebih banyak ancaman dibandingkan saat paus berkeliaran di laut lepas. Paus biru harus menghadapi sampah laut yang merajalela, tabrakan kapal, polusi suara yang hebat, dan menurunnya pasokan makanan akibat pemanasan air dan penggunaan krill komersial, sehingga pemulihan paus secara berkelanjutan sangat sulit dilakukan.

Spesies ini pulih jauh lebih lambat dibandingkan dengan spesies lain - seperti paus abu-abu, paus bungkuk, dan paus sirip - sejak berakhirnya perburuan paus komersial berskala besar, dan tabrakan kapal bisa jadi merupakan faktor yang signifikan.

"Hanya sebagian kecil kematian paus besar yang didokumentasikan sebagai terdampar karena sebagian besar paus besar tenggelam atau tidak terdampar ke pantai," lapor Cascadia Research Collective, sebuah lembaga nirlaba yang didirikan oleh ahli biologi penelitian John Calambokidis. "Kematian yang sebenarnya diperkirakan setidaknya 10 kali lebih tinggi dari yang diperkirakan oleh terdamparnya paus yang terdokumentasi."

Calambokidis dihormati secara luas atas kontribusinya terhadap penelitian dan konservasi paus. Penelitian jalur pelayarannya berhasil mengubah rute kapal yang melakukan perjalanan ke pelabuhan California untuk menjauhkan mereka dari tempat paus berkumpul.

"Saya tidak hanya berfokus pada penelitian untuk mengurangi pemogokan kapal, tetapi juga bekerja sama dengan industri dan lembaga pemerintah untuk mengimplementasikan perubahan," kata Calambokidis. Meskipun perubahan ini merupakan awal yang baik dalam mengurangi insiden pemogokan, ia mengatakan bahwa masih banyak hal yang perlu dilakukan, termasuk memperlambat laju kapal.

Sampah laut adalah masalah utama lainnya bagi paus biru, salah satu masalah yang telah mencapai tingkat yang mengkhawatirkan di perairan dunia. Sampah manusia, besar maupun kecil, telah menyusup dan mencemari setiap habitat laut dari khatulistiwa hingga kutub. Paus biru menemukan sampah laut dalam berbagai bentuk, termasuk mikroplastik, jaring ikan hantu yang sangat besar, dan semua yang ada di antaranya.

Makalah yang diterbitkan dalam jurnal Komunikasi Alam pada tahun 2022 memperkirakan bahwa seekor paus biru dapat mengonsumsi hingga 10 juta keping plastik mikro setiap hari selama musim makan utamanya. Jumlah tersebut setara dengan hampir 100 pon plastik setiap harinya. Namun, para penulis studi melaporkan bahwa hanya 1 persen plastik yang ditelan paus balin yang berasal langsung dari air yang disaring dari mulut mereka. Mangsa yang dimakan paus telah menelan 99 persen lainnya.

Masalah lain muncul ketika alat tangkap yang sudah tua, rusak, atau terbelit dibuang ke laut, sehingga menciptakan alat tangkap hantu. Jaring hantu ini merupakan bentuk sampah laut yang paling berbahaya dan dapat hanyut terbawa arus laut selama bertahun-tahun atau bahkan puluhan tahun, meninggalkan jejak kehancuran di belakangnya. Sebanyak 60 persen paus biru di Teluk St Lawrence, Kanada, pernah berinteraksi dengan tali dan jaring ikan berdasarkan bekas luka yang ditunjukkan dalam foto-foto drone. Karena ukurannya, paus biru biasanya dapat membebaskan diri dan bertahan hidup, tetapi itu tidak berarti mereka tidak mengalami trauma dan stres yang tidak semestinya. Hambatan ini tidak dapat diabaikan untuk spesies yang sudah berjuang untuk bertahan hidup.

Ini bukanlah satu-satunya kesulitan yang dihadapi paus biru, tetapi karena kesulitan yang melekat dalam mempelajari hewan pelagis raksasa ini, hanya ada sedikit data konklusif yang dapat merinci dampak negatif spesifik dari ancaman lain seperti polusi suara, peningkatan suhu air, dan pengasaman laut. Faktor-faktor ini memiliki dampak negatif yang dapat diukur pada berbagai spesies laut lainnya, sehingga masuk akal jika bahaya yang sama juga dapat menyebabkan stres pada paus biru.

Seorang penyelam berenang bersama paus biru di dekat Trincomalee, Sri Lanka. © AMOS NACHOUM

Banyak hal yang kita lakukan atas nama kemajuan justru berbahaya bagi dunia dan kehidupan yang ditopang olehnya, termasuk diri kita sendiri. Paus layak mendapatkan perlindungan dan penghormatan bukan hanya karena nilai intrinsiknya, tetapi juga karena mereka memainkan peran penting dalam fungsi planet kita.

Michael Fischbach, direktur eksekutif Great Whale Conservancy, menjelaskan bahwa paus membantu menstimulasi produksi plankton, yang pada gilirannya menghasilkan lebih banyak oksigen untuk mengimbangi dampak perubahan iklim. "Untuk kesehatan lautan, kita benar-benar membutuhkan lebih banyak paus," katanya.

Sebuah laporan yang diterbitkan oleh Dana Moneter Internasional pada tahun 2019 mendukung pernyataan tersebut: "Dalam hal karbon, seekor paus setara dengan ribuan pohon. Paus membantu mengatur iklim dengan meningkatkan pertumbuhan fitoplankton di permukaan laut, yang menangkap 37 miliar ton CO2 (karbon dioksida) per tahun."

Paus biru adalah banyak hal: megah, besar, kuat, rapuh, misterius, terancam punah, dan kritis. Namun yang paling penting, mereka layak - layak untuk hidup bebas dari berbagai bahaya antropogenik yang telah kita timpakan kepada mereka. Kita berhutang pada mereka, dan kita juga berhutang pada diri kita sendiri. Kita harus bekerja lagi untuk menyelamatkan paus, tidak hanya demi mereka tetapi juga demi kita. AD

© Alert Diver - Q3 2023