Une exploration de la terre et de la mer

It’s not every day you can witness the inner workings of our planet by taking a live look under the hood at the engine of creation. Some scientists claim that life on Earth began from hydrothermal vents in the ocean’s abyssal reaches. That realm is much deeper than where I float now, but otherwise it’s not all that different from the fascinating formation before me — a chimney below the sea in northern Iceland.

Pas besoin de sous-marin

Le Strýtan pinnacle in Eyjafjörður is a natural wonder, a unique biogeological phenomenon, and Iceland’s first underwater protected area. Towering over the bottom 213 feet below, this smectite clay hydrothermal chimney gushes more than 1,500 gallons of 162°F fresh water into the surrounding cold salt water every minute. Magma underneath Iceland warms the fresh water, which scientists estimate to be about 11,000 years old. Rich in silicon dioxide, it precipitates upon contact with the magnesium in seawater to slowly grow the chimney.

Strýtan rises to within about 50 feet of the surface. It and a cluster of much smaller structures a few miles away are the only known hydrothermal chimneys or smokers in the world that are accessible to recreational divers. Having descended to more than 100 feet, we spiral upward around the living structure. It is 10 to 15 feet in diameter and not plumb-line straight; its profile angles a few degrees in either direction here and there.

Much of Strýtan’s surface is overgrown with algae, hydroids, tunicates, and bryozoans. There are beige sea stars and clumps of black mussels. Juvenile cod tuck in close to the vertical reef, while larger adult fish hover off to the side. I am especially drawn to the white sections resembling tumorous growths — some smooth, others craggy — that are the most recent mineral deposits. Here I can see shimmering swirls of warm fresh water jetting forth, causing the nearby algae to flutter and my vision to blur. My imagination sparks, and I am convinced that if I had a microscope I would see chemicals reacting, atomic building blocks coming together, cells dividing, and life exploding into being.

Plongée avec les Vikings

Connue comme la terre du feu et de la glace, l'Islande est un pays brut et époustouflant. Des millions de touristes visitent cette nation insulaire, à la dérive dans l'Atlantique Nord entre le Groenland et la Norvège, pour admirer les chutes d'eau, escalader les volcans et ramper sous les glaciers. Très peu de gens plongent sous les vagues, mais nous ne pouvons pas résister à l'opportunité de voir autant que possible cet endroit remarquable.

To experience the diving that very few people know about, we visit Akureyri, Iceland’s second-largest urban area behind Reykjavík, with nearly 19,000 residents. The Norse Viking Helgi magri Eyvindarson settled Akureyri and the island of Hrísey in the ninth century. The town is now the diving hub (hub being a relative term) in northern Iceland and the gateway to exploring Eyjafjörður.

We cast off the lines and motor into the fjord. A knife-edged wind and swirling snowflakes make the 20°F air temperature feel below zero. My wife and I are already fully geared up, but our divemaster and skipper are still bareheaded and without gloves as they smile and chat away, apparently impervious to the elements. Wishing for even a single potent drop of their Viking ancestors’ blood will not make me any warmer, so I compensate with a drysuit, dry gloves, an 8 mm hood, and double layers of high-tech undergarments. It is only a five-minute ride in the open inflatable from Hjalteyri harbor to the dive site, where the 41°F water is sure to be bliss.

Wishing for even a single potent drop of their Viking ancestors’ blood will not make me any warmer, so I compensate with a drysuit, dry gloves, an 8 mm hood, and double layers of high-tech undergarments.

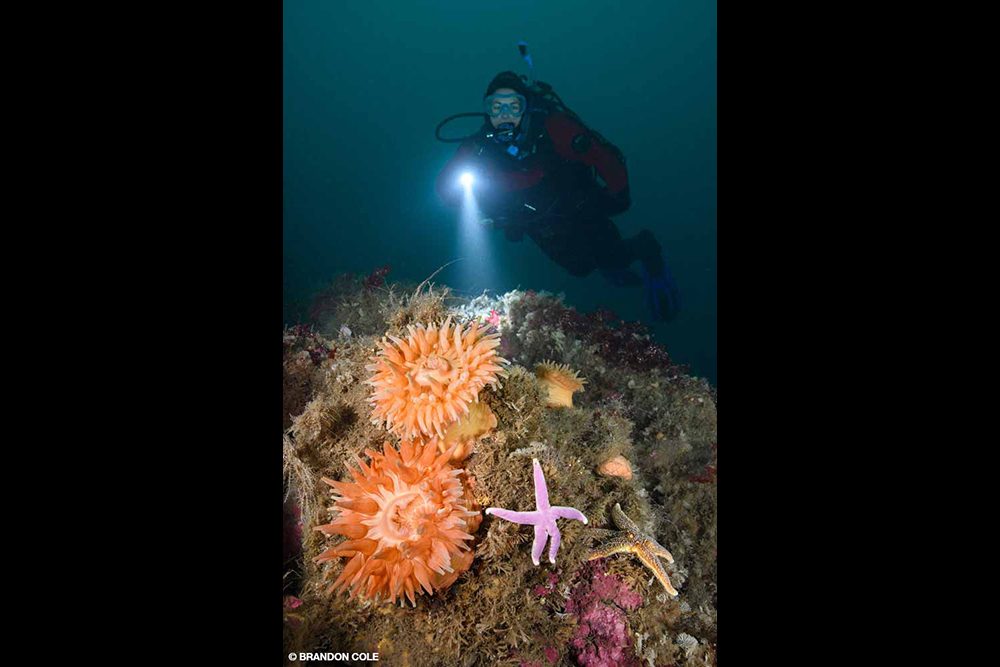

Récif à peu près circulaire dont la profondeur est comprise entre 50 et 75 pieds, Arnarnesstrýtur showcases the fjord’s other shallow hydrothermal smokers and excellent marine life diversity. Curious Atlantic cod greet us almost immediately upon touchdown. Bronzy gold with fine spots, large eyes, and seemingly too many fins, they are handsome fish, even with their gummy lips and peculiar, single wormlike barbel dangling from their chins. We swim past a stand of Laminaria tangle kelp, while a lion’s mane jellyfish drifts through the green water in the opposite direction. There are white plumose anemones resembling huge stalks of cauliflower sprouting from rock painted pink purple by coralline algae, hermit crabs, and salmon-colored nudibranchs with spiky gills.

All these species — cod excluded — evoke memories of my local diving in the Pacific Northwest thousands of miles away. All are but the prelude, however, to the wolffish Anarhichas lupus. La principale raison pour laquelle je suis ici, pour plonger avec les Vikings en octobre, est de rencontrer le cousin de l'océan Atlantique de mon loup-élan bien-aimé. Anarrhichthys ocellatus. Arnarnesstrýtur has a handful of the beauties in residence. One reclusive wolffish is tucked way back in its den, valiantly guarding a clutch of eggs. He ignores the quahog (a clam) our guide offers. A wolffish celebrity named Alex, however, excitedly slither-glides out of his crevice to devour the treat and pose with a snaggle-toothed grin. Fifty miles from the Arctic Circle, I am in paradise.

Road Trip de l'anneau

With our dive gear and underwater cameras packed away and replaced by hiking boots, snow pants, camera tripod, and drone, we rejoin the mainstream and point our little four-wheel-drive rental car east on Route 1, the famed 828-mile Ring Road that circles Iceland’s perimeter. We will travel clockwise and visit jaw-dropping sites topside, many of which have become international Instagram favorites.

It pays to be choosy with so many waterfalls vying for your time. Goðafoss (“waterfall of the gods”) reminds me of Niagara Falls with its semicircular shape. The new-fallen snow elevates this waterfall to among the trip’s best.

An hour east of Akureyri is the Lake Mývatn area, where we had planned to spend one day but stay for three. Iceland’s volcanic pedigree is on fine display here. We hike to the top of the snow-mantled Víti crater and fly via drone over the imposing Hverfjall volcano and the strange pseudo-craters at Skútustaðagígar along Lake Mývatn’s southern rim. These small craters formed about 2,300 years ago when a river of lava flowed over the lake and surrounding wetlands, resulting in steam-fueled explosions that left the divots seen today.

Des marmites de boue bouillonnante et une fumée sulfureuse et nauséabonde sifflant des fumerolles nous attendent dans la zone géothermique de Hverir. Munis de lampes frontales et de bottes à crampons, nous nous enfonçons dans l'obscurité de Lofthellir, une grotte de lave où des sculptures de glace surréalistes dégoulinent du plafond et dépassent d'un sol gelé.

Hiking along a sheep path for an hour takes us to Stuðlagil Canyon, through which the glacial Jökla River flows. Looming over this ribbon of green-blue water are sheer walls composed of hexagonal basalt columns. This magnificent, artistic, natural basaltic lava architecture was also born of fire and ice.

L'étonnante côte sud

down to Höfn on the country’s southeastern corner. We could be in Reykjavík in six hours if we push it, but that would mean missing many of Iceland’s star attractions. It will be challenging to do everything we want along the southern coast in only four days.

At the foot of Vatnajökull, the largest glacier in Europe, icebergs of all shapes and sizes in Jökulsárlón lagoon jockey for position as they flow out to sea. Here they fracture into smaller pieces to be washed ashore on Diamond Beach, appearing as precious gems gleaming on sand as black as velvet. We later join guided tours to trek over the fissure-riven surface of the mighty Vatnajökull and beneath its belly to explore ice caves glowing sapphire and cerulean.

Sturdy Icelandic ponies take us for a ride along Reynisfjara’s black sand beach near the village of Vík í Mýrdal, while winds howl and waves crash into the menacing, fanglike rock spires just offshore. We are so thoroughly drenched by misty spume while photographing Seljalandsfoss and Gljúfrabúi waterfalls that perhaps I should have pulled out my underwater camera housing for the job.

Un rendez-vous avec les plaques

We have come full circle and are back in Reykjavík, where this Icelandic saga began. But it is not over quite yet. Onboard a zodiac, we spy humpback whales and white-beaked dolphins doing their thing in Faxaflói Bay.

Although we have been gazing at the galaxy every night, we have not seen the northern lights dancing in the sky due to cloud cover and cosmic luck, so we content ourselves with the Aurora Reykjavík museum’s stellar virtual experience.

Nous marchons avec précaution sur les nouveaux champs de lave du volcan Fagradalsfjall, qui est entré en éruption il y a quelques mois à peine, puis nous trempons nos corps fatigués dans les piscines extérieures divines chauffées par géothermie du Blue Lagoon. Nous faisons le tour du Cercle d'or pour voir le geyser Strokkur et la chute d'eau Gullfoss, tout en attendant avec impatience Silfra dans le parc national de Thingvellir.

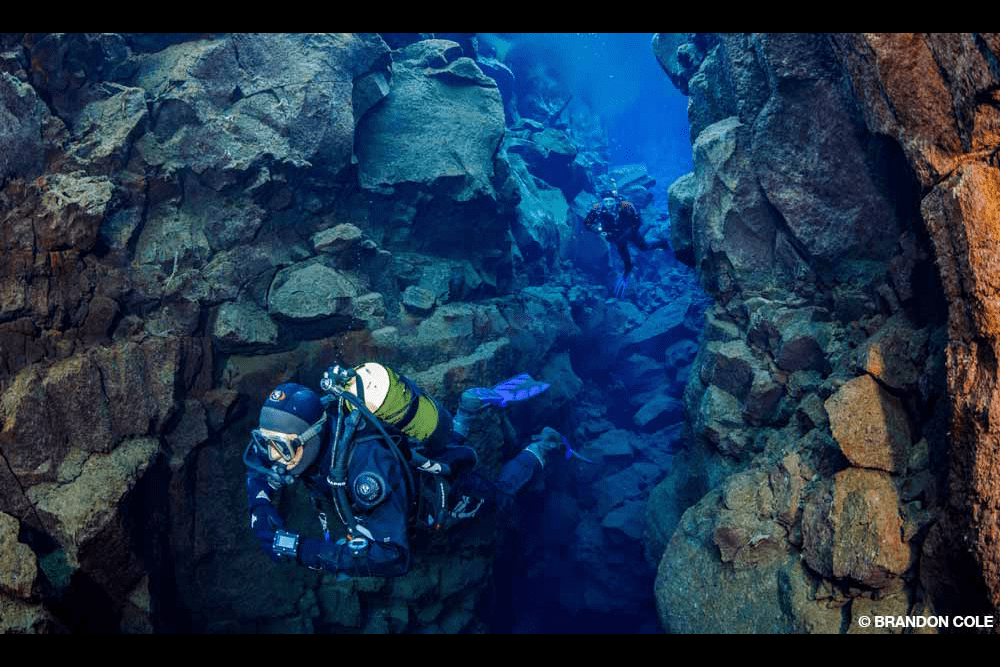

Undoubtedly the most popular dive site in Iceland, Silfra is a fissure at the northern end of Lake Thingvallatan. Created by earthquakes in 1789, the Silfra fissure cut into an underground spring, allowing glacial meltwater to flow into the site. We submerge and go with that flow, following single file behind our dive guide, swimming slowly while descending and ascending as we follow the chasm’s ragged contours.

My eyes are wide with amazement at the scenery. The fissure walls and the boulders below look as if immortal giants chiseled them. And the visibility is seemingly forever — 300 to 400 feet. The water is so clear that my freezing brain insists it must be fake — a clever, computer-generated backdrop. But the rock to either side of us is real.

We pause for a photo at a choke point, stretching our arms wide to span Silfra’s narrow gap. On one side we touch the North American tectonic plate, while the other hand grips the Eurasian plate. It was epic. I imagine that the walls are pressing in on me, but the opposite is true. The two continents are drifting apart at about an inch per year. Iceland is geology in action.

As we lumber back to the parking lot on legs not yet returned to the living, a well-dressed, elderly gentleman from a group of nondivers who have just disembarked from a tour bus asks me, “Isn’t the water freezing? Why would you do this?”

I struggle for words, still locked in mental hibernation induced by our 52-minute immersion. Sputtering to life, I smile and say, “Because it’s cool.”

With my teeth chattering, I excuse myself and waddle on, eager to dive between worlds again. After all, it’s not every day you can throw yourself into the middle of a tug-of-war between primordial forces, stealing a glimpse into what makes the boiling, freezing heart of Iceland beat.

Comment la parcourir

Se rendre sur place et se déplacer : All international flights to Iceland arrive in Keflavík (KEF), about 30 miles from Reykjavík. Once in Iceland, many visitors join organized group tours on day trips, which often provide transportation. Other visitors rent vehicles.

Conditions : People visit Iceland year-round. Tourism is more popular in summer, when the weather is warmer and the days are longer. Each season has its perks. Choose summer, for example, to hike and camp in the interior, kayak among icebergs, and see puffins. To explore blue ice glacier caves, go dogsledding, and have a chance to see the northern lights, you’ll need to visit in winter.

May through September are the most popular months for diving. Eyjafjörður and ocean dive sites are weather dependent, and cancellations due to rough seas can happen any time of year. Ocean temperatures near Akureyri range from upper 30s°F in winter to upper 40s°F in summer; it is a little warmer near Reykjavík. Visibility varies widely from 10 to 60 feet. Silfra is much less weather dependent, with water temperatures of 36°F to 38°F year-round, and the visibility is consistently excellent.

Le matériel : Portez une combinaison étanche, soit la vôtre, soit celle fournie par l'organisateur de la plongée. Certains opérateurs exigent la preuve d'une certification de spécialité de plongée en combinaison étanche ou offrent le cours. Un vêtement de pluie (veste et pantalon) est conseillé pour les activités en surface. Apportez des sous-vêtements en polaire, en laine et en polypropylène pour la superposition. Des chaussures de randonnée robustes et imperméables sont indispensables. Les photographes auront intérêt à se munir d'un trépied pour les paysages et d'un filtre à densité neutre pour les photos de cascades en pose longue.

Soutien : Dive infrastructure is limited outside of the Reykjavík and Akureyri areas. Most operators can provide all the gear you need if you do not bring your own. Many dive sites, such as Strýtan and Silfra, require you to dive with a guide. To learn more about Iceland’s marine life, visit sealife.is. Tour companies can facilitate the many topside adventures Iceland offers, such as viewing waterfalls, hiking glaciers, chasing the aurora borealis, and trekking the Highlands. Iceland’s official tourism site is visiticeland.com, et guidetoiceland.is est utile pour rechercher des lieux et réserver des excursions.

En savoir plus

See more of Iceland in Brandon Cole’s bonus photo gallery.

Watch the video below to see the Strýtan hydrothermal chimney in action.