Searching for new sea slugs

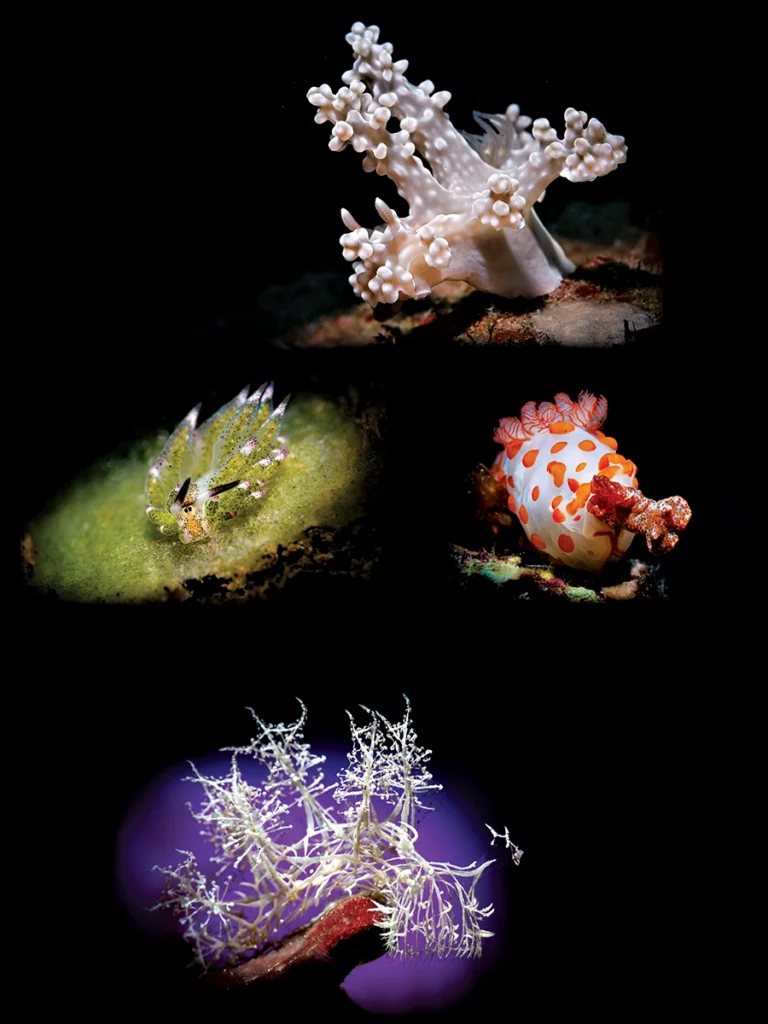

Seemingly crafted for photographers, nudibranchs are slow-moving and vibrant and have adapted to curious shapes and sizes. Aside from their fascinating appearance and cute demeanor, they also play an essential role in science and have been the focus of study for many decades.

They are helping researchers discover more about the functions of evolution and medical research, for example, and they could even help us understand the health of many ecosystems in our oceans. Nudibranchs might be adorable, but their significance cannot be understated.

Commonly called nudis or sea slugs, nudibranchs are a type of opisthobranch and are found worldwide. The most incredible variety and abundance of them are located primarily throughout the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in the Coral Triangle — a region that includes Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, and parts of the Philippines, with Anilao standing out as the premier location for macro diving.

Anilao is on the southwest tip of Luzon and directly adjacent to the Verde Island Passage, the main water corridor that flows through the region, separating Luzon from its neighboring island, Mindoro. Scientists have partnered with local researchers and dive guides since 1992 to conduct numerous biodiversity studies in the Anilao area, and their findings are staggering.

The lead scientist conducting most of the studies in Anilao is Terrence Gosliner, PhD, the senior curator in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Geology at the California Academy of Sciences. He specializes in adaptive evolution and has devoted much of his life to researching, documenting, and scientifically describing his findings. He spends significant time in the field, diving and scouring the seabed for new animal life. Gosliner is a modern-day explorer and the author of several identification and natural history books.

For context, about 3,000 nudibranch species have been discovered globally, with more than 600 different species in Anilao alone. We can attribute many of those discoveries to Gosliner and his teams of experts.

The magnitude of this kind of research requires help, so he and other scientists have enlisted groups of divers as citizen scientists to assist in the challenge. This eclectic community of devoted sea slug researchers, or sluggers, includes naturalists, self-taught experts, and even newbies. Groups can include divers of all ages, which helps them learn about our planet’s diversity firsthand while working shoulder-to-shoulder with leading experts.

At a recent Citizen Science Nudibranch Workshop, I asked Gosliner about nudibranchs, the importance of the Verde Island Passage, and the significance of such projects.

“Nudibranchs are some of the most beautiful creatures on the planet,” said Gosliner, who has been studying nudibranchs since he was a high school student on the California coast. “Their amazing adaptations tell us much about evolution, and they are important model organisms for biomedical research.”

When asked why he focuses on Anilao and the Verde Island Passage, Gosliner replied: “It’s for the same reason scientists who study terrestrial biodiversity go to the Amazon — it is simply the richest marine habitat on

the planet. Where else in the ocean can you discover new species daily, even after more than 30 years of continuous study?”

He emphasized the importance of working with local colleagues to substantiate the findings. “It is essential to work with local partners — such as dive guides, resort owners, members of the fishing community, and local governments — to build a consensus on how to sustain the livelihoods of local people, meet short-term needs, and secure the long-term protection of biodiversity hotspots,” Gosliner said. “A bottom-up partnership is always more effective than one that is top-down. Communities must have a stake in their future.

“Having citizen scientists identify species adds critically important biodiversity data for establishing priority areas for conservation,” he continued. “The collaboration of scientists and knowledgeable public members has proven to be a valuable partnership for making science-based decisions that protect biodiversity for future generations. This partnership has demonstrated that Verde Island Passage is one of our planet’s most remarkable and iconic marine ecosystems and mandates its protection.”

A food source, a mate, and a survival strategy are essential for existence. If one of these puzzle pieces doesn’t fit properly, that species may cease to exist. One-off subjects cannot endure in isolation or evolve independently.

Mother Nature doesn’t easily give up on her creations, however, and will do everything she can to alter designs through adaptive evolution. The process is slow from a human perspective, but over generations of environmental pressures, all creatures must develop new survival methods or perish. It is difficult to observe the changes broadly, but they occur right before our eyes; the proof lies in the details.

Examining a specific group of animals over an extended period can reveal a great deal about them and provide insights about their habitat’s health. Such subjects are known as indicator species and are ideal for these kinds of studies.

The science behind describing any new species is as dynamic as the subjects being described; science is not static. Following each clue to determine the exact genus and species based on systematics has evolved dramatically over the past 50 years.

Collecting multiple samples of the same new species used to be necessary, and scientists often based descriptions on scientific comparisons and personal opinions while analyzing similarities or differences between species within a similar genus. Comparative analysis continues to be frequently used before an actual description and is usually denoted by “sp.” in place of a species name after the genus, such as Siphopteron sp.

Scientists now use DNA sampling to uncover the truth behind clues, but it can sometimes complicate matters, as the ripple effect can extend to the subjects’ closest relatives and descendants. This situation arose with the largest known genus of sea slugs, Chromodoris.

In 2012 Gosliner and a colleague discovered through new sampling methods that Chromodoris consisted of three unrelated groups. In response to this finding, they reclassified them into three separate genera: Chromodoris, Goniobranchus,and Felimida.

DNA sampling techniques have advanced rapidly over the past decade, enabling scientists to trace and accurately position new species within the tree of life and assign their binomial names. Some things that haven’t changed are the nicknames guides and divers often use, such as Cinderella, Pikachu, and the Sea Bunny.

The discovery of new animal life on our planet evokes a sense of wonder and a litany of questions: How did it get there? Why is it there now? What is its food? How will it survive? With the rapid rate of discoveries and the lack of scientists to conduct proper research, there is a backlog of many types of creatures yet to be named. Our oceans are teeming with unknown life forms still waiting to be found and described.

Science and sea slug studies go hand in hand; the more you get to know them, the deeper down the rabbit hole you slide. Nudibranchs are a true gateway drug for exploring marine life.

As you slowly fin and search the substrate as a citizen scientist, you begin to notice more sea slugs. Some are smaller than a grain of rice. While their tiny size makes them hard to spot, larger sea slugs can be just as elusive.

Many nudibranchs hide under ledges or burrow into sponges while they feed. Some are nocturnal, while others are subterranean or mimic the corals they inhabit. In some cases they even harness photosynthesis to help produce simple sugars for their diet.

Most sea slugs are specialized feeders that consume specific types of food. One technique for finding these special creatures is to locate their food source: If you find their food, then you can observe them. It seems straightforward, but the rule comes with a caveat. Certain food types may appear only once every few years, making sightings of the nudibranchs that depend on them rare but thrilling discoveries.

Like plants and solar panels, a special class of nudibranchs uses sunlight to create energy. Phyllodesmium is a unique genus of sea slugs that demonstrates nature is truly better than art or, in this case, science fiction. They feed on zooxanthellae algae and retain the living algae within their tissues. Their digestive tracts connect to the algae, utilizing photosynthesis to gain energy from sunlight. This amazing phenomenon also includes the genera Baeolidia and Melibe, but only in the Indo-Pacific region. Nudibranch translates to “naked gill.” Most dorid sea slugs have an exposed gill structure that enables respiration. The gill plume is at the rear of the nudibranch and typically features a color scheme similar to the rhinophores, its main sensory organ.

The genus Aeolidia does not have the standard gill structure but instead has cerata, which appear as a thick, colorful mane along their backs, matching the color scheme of the rhinophores. They also have oral tentacles that can be short or long and resemble a handlebar mustache.

Rhinophores come in various shapes and designs, which helps differentiate species. Their primary function as chemoreceptors is to detect their prey’s chemical scents or mucus trails. Many sea slugs also have visible eye spots that can detect light, but they cannot see beyond that.

Participating citizen scientists should explore as many scenarios as possible during a workshop to gather the most information for comparison with previous studies. Since 2016 our core group has compiled a list of more than 1,000 sea slugs. During the workshops, each team — consisting of four divers and one or two guides — gets a copy of the list.

The teams explore various dive sites around the Anilao area, taking photos and searching diverse habitats. Each site yields different sea slugs, with minor overlaps usually comprising the species less finicky about their diet. The divers record all the information and submit it to the group’s data master, who then transfers the data onto a graph. The graph provides a measurement of our real-time progress during our sometimes-heated morning discussions.

The sea slugs’ color and shape are two of their notable characteristics. Due to evolutionary processes, opisthobranchs lost their gastropod shells, which forced them to adopt new strategies for protection. Shell-less sea slugs developed several new methods over generations for camouflage and self-defense.

Color variations within a species can often confuse enthusiasts into thinking they are seeing a new nudibranch. In his book Nudibranch Behavior, DavidBehrens details the form and function of the flamboyant color schemes that occur across many other species of slugs.

Slow-moving, vulnerable sea slugs need a solid plan to fend off predators. One method is aposematic coloration — using bright colors to warn that if bitten, the sea slug will unleash its secret weapon, which will likely injure and possibly kill its potential predator.

Many nudibranchs presumably acquire an unpalatable flavor from their diet, while others have stinging cells. Like other marine organisms, nematocysts are the preferred weapon for inflicting damage during an attack.

The nudibranch ingests nematocysts as a byproduct of consuming hydroids. The immature cells are then transported to the cerata or glands, where they eventually mature within the sea slug. When magnified, each nematocyst cell appears as a tightly coiled spring with a sharp barb on one end, ready to discharge with the slightest disturbance. When a fish bites a nudibranch, this self-defense mechanism involuntarily discharges, delivering fatal wounds in the fish’s mouth.

When discovering a new sea slug, it is crucial to take an identification photo first so the animal can be adequately identified before you get creative. There are various ways to photograph sea slugs. For a scientific study, capturing an identification photo from above or laterally is essential, ensuring that as much of the nudibranch is in focus as possible. It is also important to photograph it undisturbed and in its natural habitat. Using a ring flash or front lighting is ideal for this type of photography.

A completely different composition style is necessary for a more expressive rendition. The true challenge lies in merging the two styles to artistically depict a nudibranch while ensuring it can be properly identified. To achieve this, ensure the rhinophores or eye spots are in focus. Additionally, leverage the available colors and patterns.

Macro lenses, diopters, and even wide-angle lenses can be utilized effectively, provided the nudibranch occupies a significant portion of the frame. Employing negative space is also crucial for creating a portrait. A slightly upward angle enhances perspective, and getting close ensures clarity, contrast, and minimal backscatter.

Lighting is everything when shooting this way. Using a snoot, a single strobe, strobes at varying power settings, backlighting, or combinations of these techniques helps create striking photos. Nudibranchs can be photogenic even when sitting still.

From identification to art, and nestled between science fiction and actual science, nudibranchs or sea slugs — whichever name you prefer — are among the most dynamic subjects you could encounter on any dive.

Like hunting for colorful needles in a haystack, if you continue searching for yourself and science, you might accidentally stumble across a new and undiscovered life form.

Explore More

Find more about nudibranch in this bonus videos.

© Alert Diver – Q3 2025