Great white sharks are capricious fish. They are iconic, impressive, photogenic, and awe-inspiring but also frustrating. That frustration is not all about the animal — part of it is how few places in the world you can go to see them.

Divers used to visit Guadalupe Island, off the coast of Baja California, Mexico, but the Mexican government closed the area to shark-related tourism activities in January 2023. Some people speculate the ban is due to overzealous producers seeking ever-more salacious encounters, while others suggest the background motivation was something more nefarious. No matter the reason, Guadalupe is no longer an option for Carcharodon carcharias encounters.

South Africa likewise used to be a great white shark destination. Consistent populations of great white sharks were off Gansbaai and False Bay, drawn there by the extensive seal colonies that provided ample food. A fleet of shark adventure outfitters evolved to deliver tourists for in-water cage opportunities and the spectacular breaches that defined the Air Jaws documentaries. But great whites are not the apex predators when orcas are around. On a single day, three shark carcasses washed up on shore with only their livers ripped out, an alarm that signaled the demise of the enclave due to orca attacks.

Later research confirmed the sharks weren’t totally decimated but had shifted east to more hospitable places such as Algoa Bay and the KwaZulu-Natal coastline. While the sharks are there, like we know them to be off the northeastern U.S. and the Farallon Islands off California, you can’t consistently or predictably encounter them in any one place. In addition, there aren’t reliably favorable sea conditions or regulations supportive of in-water viewing operations.

That leaves South Australia as the last shark standing in terms of a destination for great white shark cage diving — but it is not a slam dunk. I’ve made the trek seven times now, including a couple of trips back in the slide film era, and have had productive encounters on five. On my most recent trip in October 2023, we had shark encounters from the moment we arrived in the Neptune Islands until we left five days later.

The best shot I got from that trip — maybe from any trip — was on the final bait toss. The captain said we had to pull anchor and head back to port, but we could have one more chance. As I sat on the swim platform with my shark wrangler and my topside camera at water level, prefocused on where I hoped the shark might emerge, I pondered the rare privilege of being in the presence of these majestic predators again.

When the shark popped up in precisely the right place, my camera’s rapid motor drive clicked away to nail the shot that now appears on the cover of this magazine. The dopamine coursing through my brain at that moment guaranteed I would return for an eighth shark expedition.

That’s how the trip ended, but it began with a long airplane ride from Miami, Florida, to Doha, Qatar, to Adelaide, Australia, and then to Port Lincoln, South Australia. The time and expense required for a South Australia great white shark expedition is a dealbreaker for many travelers from North America, but for those who go, there are two options for operators licensed for cage diving activities within the Neptune Islands Conservation Park: The liveaboard MV Rodney Fox books multiday expeditions, and Calypso Star Charters does day trips.

The Neptune Islands are two island groups — the North Neptune Islands and South Neptune Islands — in the Great Australian Bight, a large, open oceanic bay off Australia’s southern coast. Given the distance and vagaries of the sea, the trip requires big, stable, seaworthy boats to make the trip, even though there are protected anchorages once you get there. It is a three-hour run between Port Lincoln and the Neptune Islands, so be aware that six hours of day excursions will be spent in transit rather than cage diving.

Australian Sea Lions

A great differentiator for South Australia shark adventures is that there is more to see than just sharks. Most tours can include a visit to Hopkins or Grindal Island to see Australian sea lions (Neophoca cinerea). They are one of the most charismatic and rarest pinnipeds, with an estimated population of 10,000 to 12,000 worldwide.

We visited twice, arriving in the morning on our way to the Neptune Islands and then in the afternoon on our return to the mainland. The morning encounter was amazing — we kept our distance according to the regulations, but the sea lions eagerly swam right up to us. By the afternoon they were warm and cozy on the beach and totally indifferent to our presence.

As we dropped anchor from our small tender that morning, the sea lions immediately swam out to greet us, doing barrel rolls and spy hops, fully ready to engage with us in the water. Close encounters were a given as they swam directly to our dome ports and zoomed around the kelp-covered seafloor in only 15 feet (4.6 meters) of water.

The greatest challenge to this encounter is not proximity — if the sea lions are in the water, they will get close — but rather buoyancy issues. You might be wearing a drysuit or more neoprene than you are used to, and you may be using rental dive gear since you don’t need your own buoyancy compensator, regulator, or fins for cage diving. Working out how much weight we needed cost some of us significant opportunities with the sea lions. But if you get past the initial gear tweaks, it is a glorious experience. You might not leave a productive day of shark diving to backtrack a couple of hours to dive with Australian sea lions, but as a splash on the way out during your first day, it is a South Australia must-do.

Great White Sharks

After our time with the sea lions, we were ready for the main event: great white sharks. Your boat will arrive at either North Neptune or South Neptune. North Neptune is closer to Port Lincoln, the mainland hub for South Australia shark diving, so day trips typically go there, while liveaboards can visit either island group. Our tour primarily concentrated on South Neptune, but we motored to North Neptune for one day midweek to avoid leaving any opportunity untested.

We had good luck at both places, but the legacy of consistently chumming the water at North Neptune has had the unintended consequence of attracting large schools of trevally jacks around the cages. It is challenging to compose a photo of a distant great white through a wall of highly reflective silver fish surrounding the cage.

We retreated to South Neptune after a day of frustration and minimal significant photos. We would have been happy to stay around the northern islands if only the sharks were there, which sometimes happens. On this trip we had better luck photographically at South Neptune, where I took all the photos for this article.

A Day in the Life of a Cage Diver

The crew is busy with the task of attracting sharks from the moment the anchor sets. A large tub of frozen, minced fish entrails (the chumsickle) goes into a tub on the dive platform. As seawater constantly flows into the tub, the crew chips at the slowly defrosting mass so the blood and bits of flesh create a slick that advertises our presence to any great whites in the area. This activity continues in the background throughout the shark dive.

A bit of tuna, usually the head and gills, is typically the main attractant. The shark wrangler attaches it to a line, repeatedly throws it in the water, and then drags it back to the swim platform. The bait is rigged with a biodegradable sisal line, so there is no possibility of harming a shark that gets the bait. The goal is not to feed the shark but to attract it near the cage while ideally never impacting it. The conservation park has clear rules of engagement, and the operators know their permits depend on compliance.

The most relevant rules affecting cage divers are to not harm or deliberately feed the sharks, avoid leaving any fish-based attractant in the water unattended or disposing of it in the park, and stop any form of shark attraction for 15 minutes if a shark “bites, takes, or ingests any unminced fish-based attractant or makes forceful contact with the underwater enclosure, equipment, or vessel.”

The wranglers do their best not to allow the sharks to take the bait, although it does happen. The sharks would become satiated or bored if they got the bait every time; if they never got it, they would give up. Getting bait occasionally and randomly keeps them highly engaged.

While the shark wranglers are perpetual motion machines on the back deck, shark inactivity might lull guests into torpor. Just because we don’t see sharks on the surface doesn’t mean they aren’t there. Great whites are stealth predators and often surprise everyone with a massive breach in pursuit of the bait. The activity accelerates with the frenetic shout of “shark” from the stern. Whoever has their scheduled turn in the cages needs to be in their wetsuits and ready with their cameras prepped for action.

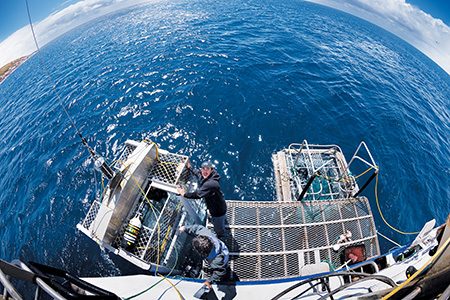

Our boat for this trip, the MV Rodney Fox, has two cages. One is a surface cage tethered to the port stern, while a crane lowers the starboard submersible cage to the kelp-covered seafloor 70 feet (21 meters) below. This dual-cage system can accommodate four to six cage divers at a time. A long hose and regulator feed compressed air to the surface cage, so no scuba certification is necessary. Submersible cage divers use traditional scuba tanks, BCs, and regulators, so they must be certified and comfortable diving a flat 70-foot profile, typically on air. Nitrox tanks are available for an additional charge if divers book them in advance.

A bin in the bottom cage contains bait. The cage captain stomps it to smithereens, and the bait floats into the water column to attract sharks and other colorful subtropical seafloor inhabitants. There isn’t a tethered bait to lure a shark near the cage, but the cage becomes an ecosystem of its own, and the sharks are often curious.

I didn’t have a super close encounter while in the submerged cage, but others in our group did. You need to invest a fair bit of time in the bottom cage to make your own luck. It is a more random experience than the surface cage, but South Australia is the only place in the world to experience being in a cage on the seafloor. Even in Guadalupe, where most boats offered a subsurface cage, the water was so deep that the cage was still tethered amid the featureless blue. The bays in South Australia are shallow enough to place the cage on the bottom, revealing a seagrass and kelp background and different marine life from what you would encounter at the surface.

The surface cage was a happening place during our time at South Neptune. With only nine cage divers — we intentionally booked the charter at half capacity to maximize cage time — and two cages, plus all the topside photography opportunities from the shark action at the surface, no one suffered from shark deprivation. We were lucky to have active sharks each day, but that isn’t always the reality.

Every time I get amped up talking about stellar shark encounters, I recall the trips where the action was slow and even the one where we were totally skunked. These situations happen for various reasons. A whale carcass in the Spencer Gulf might attract the great white sharks away from the Neptunes, or tuna fishing boats from Port Lincoln could entice them away from the islands with their large nets of live tuna towed behind them.

The great whites are mostly there for the long-nosed fur seals that inhabit the craggy shorelines along the Neptune Islands, and the little bit of minced bait that occasionally washes into the sea along with some tuna gills from our throw lines isn’t going to sustain a 16-foot shark. Yet as long as they find it a good game, this remains one of the truly great adventures for any marine megafauna lover.

How To Dive It

When to go: The Australian summer (North American winter) offers the warmest water and a good chance to see sharks. February to May is cooler, and August to October has the coldest water temperatures. The highest recorded numbers of sharks per day in recent years peaked from September to November.

Getting there: Port Lincoln is accessible through Adelaide via QantasLink and other regional carriers. They fly smaller aircraft and have restrictions on your carry-on’s size and weight. You’ll need to be creative with how you pack for South Australia: Two checked bags at 50 pounds each and a small hand-carry at 15 pounds are their published limitations.

Cage diving: You’ll need a good wetsuit (7 mm recommended) or drysuit for water in the 60s°F (about 15°C to 20°C), plus booties, a hood, and gloves. Bring a comfortable mask, but you don’t need a BC or fins unless you want your own gear for diving with the sea lions. It’s a good idea to have a snorkel even if you don’t use it. The surface cage uses surface-supplied air. The bottom cage divers will use a conventional tank and scuba gear without fins. You will need a dedicated dive computer for the submersion to 70 feet with a flat profile, and if you do it twice a day, monitor your bottom time and no-decompression limits.

Hyperbaric treatment: While surface cage divers can’t get into bubble trouble, staying too long in the bottom cage can be a hazard. The hyperbaric medicine unit at the Royal Adelaide Hospital is the South Australian state referral service for hyperbaric and dive medicine. They offer a hyperbaric oxygen treatment facility with a state-of-the-art triple-lock recompression chamber that can treat up to 20 patients across two compartments.

Water clarity: Visibility is typically 60 to 100 feet (18 to 30 meters). The baiting process can create particulate matter from the chumming and the sharks biting through the attractant.

Topside lens choice: The athleticism of these sharks will impress even the most ardent underwater photographer, and breaches are not unusual. An 80-200mm zoom lens was a good focal length to capture the moments when teeth, eyes, and fins were above the water at the stern.Shark activity: A database of shark encounters by Calypso Star Charters from 2011 to the present is at tinyurl.com/calypsostar. It can help you plan well in advance which months are best for shark encounters so you can try to avoid the dreaded shark drought during your South Australia great white shark adventure.

Explore More

See more great white shark action in Stephen Frink’s bonus photo gallery.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2024