What diver isn’t enchanted by an octopus, especially a beguiling beauty with the reputation of an assassin? Even though we searched for legendary blue-ringed octopuses across their territorial waters of the Asia-Pacific, it took five years before we made our first sighting in Lembeh Strait.

When our Indonesian guide pointed out the long-sought treasure hunkered down on a patch of rubble, we couldn’t detect a thing. Only after he gently traced its broken profile with an outstretched finger did a thimble-sized, sack-like mantle and sucker-lined arms take shape. We realized why it had taken so long to track down the celebrated predator: Our search image had been all wrong — our unschooled eyes had been programmed for shimmering rings rather than deception.

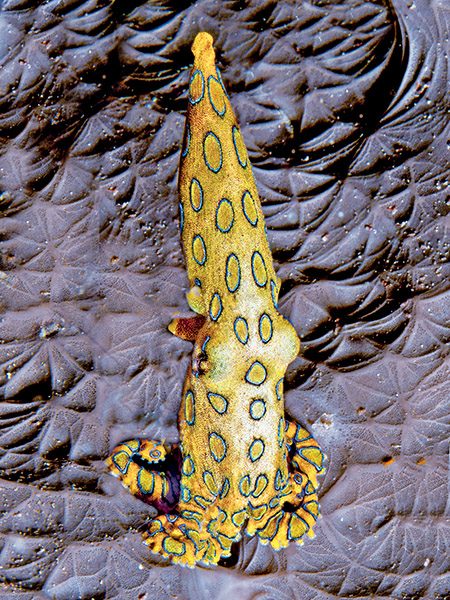

Much like that first encounter, when blue-ringed octopuses perceive danger, they routinely freeze in place behind an impenetrable haze of camouflage. These amazing disappearing acts, powered by chromatophores (flattened, pigment-blending sacs stacked like pancakes in the outer layer of skin), are masterpieces of deception. After the masquerades have been breached, their pulsing array of 60 or so namesake rings blazes into action.

Our guide’s fluttering fingers instigated the phenomena, as the cryptic illusionist instantly transformed into an eight-armed octopus the size of a ping-pong ball, decorated from head to arm tips in high-visibility, blue-green iridescent rings — a brazen warning of the little cephalopod’s deadly nature.

The venom they are advertising is a product of symbiotic bacteria secreted in saliva and administered by a chitinous beak. Although deadly, it’s scarcely a worry for divers. The potent predators would rather use their toxic adaptation to paralyze ensnared crabs, their preferred food. The conspicuous rings, generated by multilayered reflectors, function independently of the chromatophores. Ultimately, if all their elaborate wizardry fails, they are left with one option: fleeing.

By chance, our arrival in Lembeh the next year closely followed a mass settlement event of pelagic, paralarval blue-rings the size of dew drops. From the time the see-through specks parachute to the sea floor, the rapidly maturing, short-lived eating machines have little time to waste. Later, as sexual urges ripen, solitary males go on the prowl for mates.

While climbing back aboard the old water taxi chartered as a dive boat, our guide’s head broke the surface long enough to yell, “They’re fighting!” Even though I was out of film, out of air, and not exactly certain who “they” were, I was back in the water in record time.

The guide’s eyes were as big as biscuits as he pointed out two blue-rings facing off inches apart. As if on cue, one jumped the other, provoking a blurred tangle of writhing arms. Seconds later, the pair popped apart, panting, punchy, and glaring with rage across the sand. Two similar altercations followed before the brawlers called it a draw and slipped away in different directions. We attributed the tussles to a territorial dispute and left it at that.

Back at the site the following day, a larger blue-ring jetted across a patchwork of algae and headed down the slope. We were after it. Several stops later, it plopped on the sand in front of a smaller blue-ring. I suspected another fight, but instead the undersized octopus calmly wrapped its arms around the back of the visitor’s mantle. And there it remained firmly in place — no struggling, no antics, no drama — as the larger octopus nonchalantly went about its business, even swimming with the hitchhiker in tow.

A forgotten piece of lore slipped to mind: Blue-ringed males are substantially smaller than females. What glorious luck to happen upon mating blue-rings! I reluctantly surfaced an hour and a half later, leaving the pair still blissfully coupled. Sadly, that dive marked the end of easy blue-ring watching. As if a switch had flipped, the little octopuses became scarce except for a single female discovered days later carrying a clutch of eggs beneath a protective skirt of arms.

After arriving home, I searched the internet for blue-ringed octopus details. Among countless references to their notorious poison, I found a promising research paper titled “Sex identification and mating in the blue-ringed octopus,” published in 2000 by Mary Cheng and Roy Caldwell. The study was a gem and explained much of what we witnessed underwater. The researchers discovered from laboratory observations that females regularly couple with a male for as long as two hours at a time and normally accommodate multiple males over multiple days. Once the males mate, they are ungraciously ignored or eaten or they wander away to die.

Without question, our favorite nugget gleaned from the study concerned the unaccountable octopus fight. Males, isolated from other members of their species throughout their early lives, cannot distinguish females from males until they attempt to mate, which may explain the brief, volcanic clashes between the two males in training.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2024