A breath of air — nothing more, nothing less

A STATEMENT ON FRED BUYLE’S WEBSITE briefly explains his approach to underwater photography: “To take his pictures and videos, Fred uses a simple formula: the water, available light, a camera, and one breath of air, nothing more, nothing less.” I would add to that list an extraordinary eye for composition and a passion for placing himself wherever the photo opportunities are. The images in his portfolio represent decades of travel to exotic destinations far from his home in the Azores. He has tolerated fewer overweight baggage fees than other photographers might, for his life and aesthetic are remarkably minimalistic for a man of such accomplishment.

Buyle came to photography naturally — some might say genetically. His great-grandfather was an innovative and acclaimed photographer in Brussels and portraitist to the Belgian royal family. His grandfather was a fine art painter, and his father was an advertising and fashion photographer in the 1960s. Buyle missed the active era of his father’s life in fashion photography, as he was retired from that career by the time Buyle was born.

For at least two months each summer the family sailed to Denmark, the United Kingdom, and Norway. Boating was a family passion, and while his parents weren’t divers, Buyle was curious about all things related to the ocean. He began reading voraciously at 4 years old. By the age of 7 he was satisfying his curiosity about the underwater world by snorkeling, and he started spearfishing a few years later. As he had to go deeper for game, he learned to equalize. He spent more time observing than spearing fish, and freediving became a part of his life.

As a teenager he got his dive certification in Belgium and became a PADI divemaster at 18 and an instructor a year later. Depending on a tank and regulator, however, never resonated with him as much as the one-breath aesthetic. Freediving became a more organized sport in the 1990s, and Buyle was a part of it. In 1995 he set his first world record of 167.3 feet (51 meters) in the variable-weight category and followed it in 1997 with the constant-weight record of 173.9 feet (53 meters). He beat that record later in 1997 to 190.3 feet (58 meters) and in 2001 to 213.3 feet (65 meters). In 1999 he passed the most challenging barrier in freediving, 328 feet (100 meters), becoming only the eighth person on record to do so.

You were clearly established as freediving royalty by 2000, but when did you start your underwater photography?

By 2002 I had grown bored with freediving for records, but I wanted memories of what I saw underwater. About that time magazines became interested in freediving competitions, so photographing freedivers was a natural transition for me. The elite freedivers were a small community, and we had mutual trust. I had the skills to get deep enough to take a dramatic photo, yet I knew enough about the culture to stay out of the way and not interfere with the dive. You can’t ask your model for one more take during an international competition, so I learned to get it right the first time.

I took my first digital underwater photos in 2001, so if you began shooting in 2002, I’m guessing you never shot film.

That’s true. I began my underwater photography using a Nikon Coolpix digital camera. The digital files weren’t too bad, but the shutter lag was horrible. You had to press the shutter release and anticipate where your subject would be when the camera took the shot. I moved to Canon digital cameras for better-quality files, more lens options, and an improved shutter. Cameras continued to improve among all manufacturers, and by 2016 I had switched back to Nikon and eventually became one of their ambassadors. I had been shooting a Nikon D810 but have upgraded to a Nikon Z 7II in an effort to have a smaller and more streamlined in-water footprint.

Your style now seems to be big animals, often with freedivers, but with an emphasis on charismatic marine megafauna.

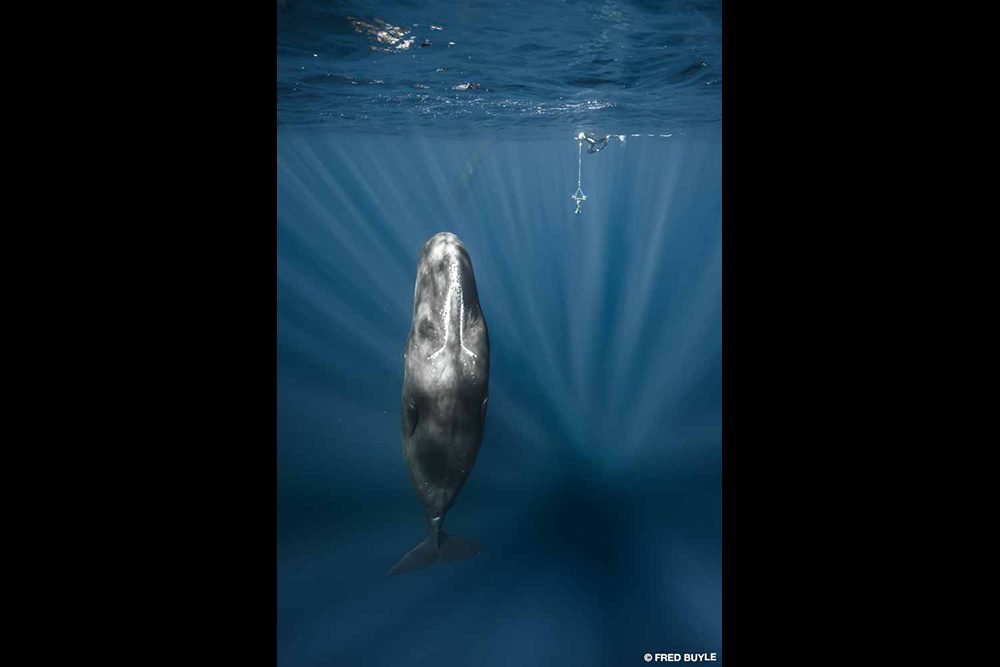

I’ve always loved being with big animals, but freediving is very much a team sport. We all know the risks of shallow-water blackout, so we travel and dive together. It is important to be a good safety role model, and even today I might drop down to 200 feet for a photo opportunity, so we rely on the security that comes from watching each other’s backs. Our safety protocols are always in place, even if it is a relatively shallow dive to photograph sleeping sperm whales. Since two or more of us are always in the water, I can place a freediver near the marine life. It provides scale and human interest, and my buddies want to be next to big critters anyway. I have the benefit of being there to get the shot.

The diversity of your subject matter — great whites, tiger sharks, mantas, whale sharks, sperm whales, and even belugas — gives a sense of how geographically committed you are. Since you can travel lightly without strobes and scuba gear, do you feel that contributes to a minimalistic approach?

That is how I travel and how I live. I am very minimalistic. I live in the Azores so I can be near the sea. When conditions are right, I can grab my camera, quickly jump on a boat, and find myself in the water with blue sharks, mobula rays, or whatever else is out there. You never know what kind of encounter you might have, and interacting with it all is the great joy of my life. But my travel isn’t random. I have an idea of what to shoot and where to go to succeed.

In 2007, for example, I wanted to get some shots of great white sharks in clear water. Mark Addison had luck freediving with sharks in the Indian Ocean off the east coast of South Africa. He had discovered that if we waited for warm, clear water to come in over the pinnacles, we might encounter great whites. Swimming without cages was rare at the time, but Mark had often done it and helped me realize it was possible. It turned out to be a magical experience that significantly advanced my understanding of shark behavior. That year my photos of freedivers swimming peacefully alongside huge tiger sharks in South Africa were widely distributed and became my first viral images.

A lot of my other work in conservation circles happened because freedivers can do things that are impossible on scuba or rebreathers because they are too cumbersome and intimidating to the animals. We attached acoustic tags for tracking migration to scalloped hammerhead sharks in Rangiroa, Tahiti, along the Eastern Pacific Corridor (the Galápagos, Cocos, and Malpelo), and to great whites off Guadalupe Island in Mexico. Our unobtrusive presence made us valuable underwater assistants to the shark researchers.

Your primary camera is the mirrorless Nikon Z 7II, which creates less water resistance. Do you find that feature significant?

My equipment evolution is always for size and efficiency. When I travel I have one checked bag with my clothes, fins, mask, snorkel, and wetsuit. My carry-on backpack contains one camera and housing, a spare camera body, and two or three lenses. I don’t need strobes or macro lenses. For me, it is all wide-angle, available light, and one breath of air.

Speaking of one breath, do you have to constantly train to keep yourself at peak freediving efficiency?

I haven’t trained for freediving since 2004, when I quit competing. It is about having a healthy lifestyle. I swim quite often, ride my bike, and pay attention to what I eat. Stretching helps me quite a bit, and I have a rowing machine for when the weather is bad. Honestly, I’d rather work in my garden or take a nice walk every day. I’m fortunate that I can still accomplish the work I want to do, and I look forward to the next grand adventure!

See more of Buyle’s work at nektos.net.

Explore More

See more of Fred Buyle’s work in a bonus photo gallery and in the videos below.