Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary

About 200 million years ago, as continents were breaking up and drifting apart, the Gulf of Mexico started to form. As continental drift continued, salt and sediment deposits interacted to form the salt domes that are part of the unique nature of the Gulf’s seafloor. Then about 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, the perfect combination of depth, sunlight, clear and warm water, current-riding coral planulae — likely from 400 miles (644 kilometers) away off the Mexican coast — and hard surfaces for coral attachment came together to create coral reefs at the East and West Flower Garden Banks.

Near the turn of the 20th century, fishers described the two picturesque reefs full of colorful marine life about 100 miles (161 kilometers) south of the Texas–Louisiana border as “flower gardens,” and the name stuck. In 1992 the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS) became the 10th U.S. marine sanctuary. The East and West Flower Garden Banks are about 13 miles apart and have caps of 250 and 100 acres (40.5 hectares) of coral reef, respectively. The tops of the two banks host more than 20 species of corals, around 300 species of fish and an abundance of algae, sponges, cnidarians, bryozoans, crustaceans, mollusks, echinoderms and larger marine life. The Flower Garden Banks are among the healthiest coral reefs in the Western Hemisphere.

The sanctuary expanded in 1996 to include Stetson Bank as the third reef. This smaller bank about 30 miles northwest of West Flower Garden Bank has slightly cooler water, where you will find fewer coral colonies yet a significant sponge population and more tropical fish.

Coral Reefs

Descending to the reef top at about 55 feet (16.7 meters) at either East or West Flower Garden Bank, a dense and extensive greenish blanket of sea life comes into view. Finning closer to the bottom reveals a remarkable expanse of tightly packed hard corals and sponges stretching to the underwater horizons 100 feet (30 meters) or more in every direction. Sea fans and soft coral whips typically seen on a Caribbean or Florida reef are absent here but can be found off the reef cap in the deeper and darker mesophotic zone beyond the 130-foot recreational dive limit.

Green and brown star coral polyps cover the coral boulders, many of which are larger than a small car. Most formations are studded or fringed with orange and yellow sponges, and many take on subtle hues, fascinating shapes and surface patterns that make them appear as natural, living sculptures. Peculiar corals stand in toadstool shapes caused by bioerosion of their bases.

Schools of blue creole wrasses, brown chromis and other damselfish hover over the mountainous star corals and symmetrical brain corals, while parrotfish, rock beauty angelfish and Spanish hogfish meander around the reef. Squirrelfish, eels and puffers hide in the shadows under the overhangs. Other tropical residents include barracuda, angelfish, reef butterflyfish, redspotted hawkfish and scrawled cowfish. Resident yellowhead jawfish along with visiting peacock flounders, stingrays and even nurse sharks occupy the sand patches and alleyways that section off the nearly continuous spread of corals.

After sunset hundreds of red night shrimp appear atop the reefs and reflect dive lights like miniature beacons shining amid sleeping parrotfish and a variety of crabs. Besides an impressive array of stony corals and Caribbean tropical fish, FGBNMS attracts much larger animals such as manta rays, loggerhead turtles and silky sharks.

Uniqueness

Several features, encounters and events make FGBNMS an extraordinary place to dive. Its remote location more than 100 miles (161 kilometers) from shore translates to fewer divers and recreational hook and line fishers. This buffer from shoreline activities and development helps account for the exceptionally healthy coral reefs. It also requires extra vigilance in dive planning and execution since it’s in the open ocean with no nearby lees. No other recreational dive destinations for coral reefs in the continental U.S. are as remote as FGBNMS.

The annual mass coral spawning event at FGBNMS is more intense and spectacular than just about anywhere else in the Atlantic–Caribbean region. Seven coral species are known to participate in this event that resembles an upside-down snowstorm. The tiny bundles of spawn gradually float to the surface, where the reproductive marvel occurs. This remarkable phenomenon usually happens seven to 10 days after the August full moon. The heaviest underwater blizzard often occurs in the evening of the eighth day after the full moon.

For reasons that scientists still do not fully understand, hundreds of scalloped hammerhead sharks abandon the cold inshore waters to feed in the warmer Gulf Stream gyres at the East and West Flower Garden Banks every year from February to early April. You are not guaranteed an encounter like in the Galápagos Islands, but FGBNMS is a superb alternative for seeing these animals in the U.S. Schools of spotted eagle rays in squadrons of a half dozen or more sometimes cruise through the area during the winter months. Winter diving conditions are less stable than in the summer, so be prepared if traveling from out of town.

Majestic and mysterious oceanic manta rays are present year-round, and manta aficionados have nicknames for the regulars and can quickly identify them by their unique body markings. These gentle plankton feeders appear when least expected and often entertain divers with soaring maneuvers and barrel rolls.

Working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Joshua Stewart, Ph.D., and colleagues from the sanctuary used 25 years of data to determine that the manta rays at FGBNMS are smaller than typical populations studied around the world. This research, along with other evidence, confirmed that 95 percent of the oceanic manta rays in the sanctuary are juveniles. Published in June 2018, the completed study supported recognizing FGBNMS as the first manta ray nursery. Two species of smaller Mobula rays, the lesser devil ray and sicklefin devil ray, sporadically cruise through the reefs during the spring and summer.

Whale shark encounters are also possible at FGBNMS, with sightings every summer but not on every trip or every week. There are no guarantees, and some years are better than others. You are most likely to spot them from July to September, when conditions are usually calmer on the surface. I have encountered whale sharks at all three sanctuary banks and the HI-A-389-A platform inside the East Flower Garden Bank boundary. Sometimes these gentle giants cruise straight through the reef without slowing down, and other times they will stay close to the surface and slowly circle your boat for an hour or more.

FGBNMS hosts 260 species of bony fish. That may not seem special, but the number of unusual fish found there is impressive. The odd, triangular, smooth trunkfish is typically black with white spots, but a variation found only at FGBNMS has a brilliant golden body with black and white spots. The cause of the color variant is unknown. Both blue and queen angelfish are abundant here, and the two species do more than mingle. They produce a hybrid called the Townsend angelfish, which has a variable mix of traits from its two parent species. The Mardi Gras wrasse, which features colorful body patterns reminiscent of its namesake, was first identified as a new species in 2008 and is found only in the sanctuary and some of Mexico’s reefs near Veracruz. You can also see the interesting and somewhat unusual knobbed porgy, yellowtail reeffish and tusked goby.

Diving Oil and Gas Platforms

Most weekend and three-day, Monday–Wednesday weekday trips to FGBNMS include at least one dive at an oil and gas platform located a short distance from the East Bank. The unintended but serendipitous consequences of these industrial structures are the amazing ecosystems on, in and around them.

Fuzzy white hydroids, red encrusting sponges and tiny colonial anemones blanket the steel surfaces, and varieties of colorful blennies rely on empty barnacle shells for safe havens from predators. Tessellated blennies poke out their heads enough to expose their flamboyant faces and otherworldly antlers. Yellow variations of seaweed blennies have lemon-colored bodies with blue streaks radiating from their eyes. Angelfish, cocoa damselfish and butterflyfish flutter around large stands of purple and brown tube sponges attached to the structure’s legs. Schools of silky sharks regularly circle outside the framework, and loggerhead turtles sometimes feast on sponges attached to the artificial reefs.

Stetson Bank

Stetson Bank, the sanctuary’s third marine-life hotspot, is about 70 miles (113 kilometers) south of Galveston, Texas, and about 30 miles (48 kilometers) northwest of the East and West Banks. Like those, it also sits atop a salt dome. Unlike true coral reefs bedded on hard limestone, Stetson’s substrate is softer siltstone and claystone.

At only 36 acres (15 hectares), Stetson Bank is the smallest of the three reefs and supports a more modest range of coral, with at least nine species. It is still an exceptional dive by many measures. Stetson is a magnet for thrilling marine life such as rays, hawksbill turtles and sharks. The Stetson reef cap features a series of uplifted siltstone ridges and pinnacles encrusted with sponges and fire coral where spiny oysters, arrow crabs, feather dusters and an array of other invertebrates vie for space.

The Sierra Madracis coral near mooring buoy three is not only the largest coral formation on Stetson, but it’s also one of the most visually stunning and lively displays of ten-ray star coral in the entire sanctuary. Schools of crimson creolefish hover overhead, while spotted morays poke out their heads from cubbyholes. The many recesses in the Madracis formation also provide perfect hideouts for spiny lobsters.

Stetson’s tropical fish community is denser and seems to have more juveniles than the other sanctuary reefs, making it a favorite for tropical fish watchers and photographers. Memorable encounters include spotted scorpionfish, flashy sailfin blennies in the sandflats at mooring buoy one and the golden variety of smooth trunkfish. A blue cruiseway periodically frequented by sharks is just off the steeply sloped north wall along the edge of the reef cap from buoys one to three.

Sanctuary Expansion

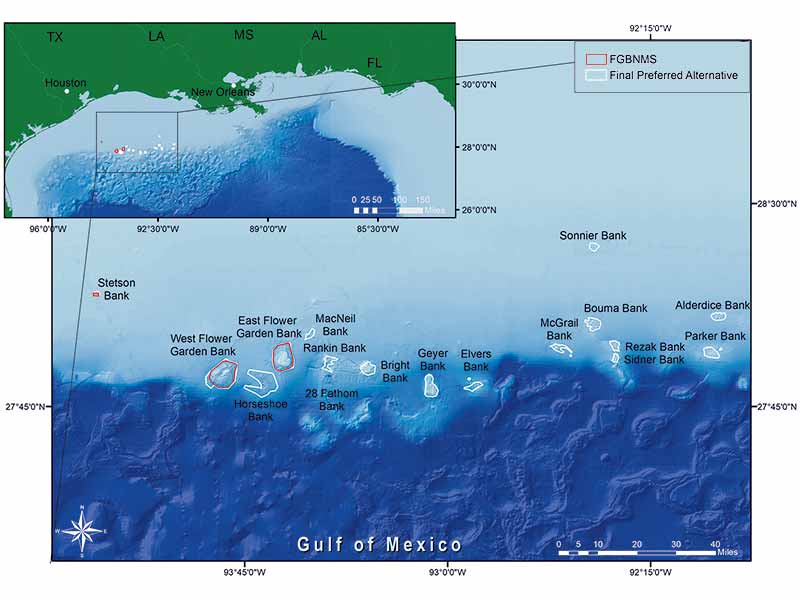

An effort to further expand FGBNMS began in 2007. Exhaustive marine biological research, scientific analysis, consultations with agency partners, and inputs from stakeholders and the general public culminated with a 2016 expansion proposal. After further conversations, recommendations and public feedback, NOAA evaluated and revised their earlier expansion recommendations.

In January 2021, NOAA released its Final Rule to the Federal Register specifying the sanctuary expansion from three reefs and 56 square miles (90 square kilometers) to 17 reefs and 160 square miles (257 square kilometers). The expansion and its protective restrictions took effect on March 22, 2021. The expanded sanctuary is like a necklace of connected bank boundaries that stretches across the Outer Continental Shelf. Of the 14 new sanctuary banks, three have reef caps within recreational dive limits, but the tops of two of the three are close to 130 feet (40 meters).

Sonnier Bank, located 83 miles (134 kilometers) off the Louisiana coast, is a cluster of eight peaks, two of which are within recreational depth. Its terrain resembles Stetson Bank but with outcrops loaded with elephant ear sponges and fire corals. Vast schools of horse-eye jacks cruise the reef tops, and roughtail stingrays are often visible in the sand patches.

Bright Bank, 124 miles (200 kilometers) off the Louisiana coast, tops off at 112 feet (34 meters) deep. Several coral-studded boulders are scattered across the bottom among hovering schools of brown chromis and creolefish. An excavated pit with abandoned equipment is the scar of a treasure-hunting misadventure from a previous era.

Geyer Bank is a tiny, pear-shaped formation about 30 miles (48 kilometers) east of East Bank. It has two peaks, with the shallowest jutting to 105 feet (32 meters) deep. The payout of this advanced dive is the massive swarms of reef butterflyfish so dense you’d think you are on a Pacific reef. Most of the other banks in the expanded sanctuary have depths near or beyond 200 feet (61 meters), but McGrail Bank to the east of Geyer is a true hard-coral reef that starts at 144 feet (44 meters) and is accessible to technical divers.

If you like the idea of a liveaboard adventure with remote, open-ocean diving where your dive boat is likely the only one on the reef, you’ll love a trip to Flower Garden Banks. It remains one of the best-kept secrets for wilderness diving in the continental U.S., where you can expect rare encounters such as a longlure frogfish on a sponge, scalloped hammerhead sharks feeding or a whale shark swimming by. After more than 50 years of diving in destinations all over the world, I never take for granted my trips off the Texas coast for the magic of my hometown reefs.

How To Dive It

Getting there: Three dive operators visit FGBNMS: one scheduled and two by charter. Boats cannot anchor in the sanctuary, so all boats use mooring buoys; East Bank has seven, and West Bank and Stetson have five each. The two charter operators cater primarily to spearfishers for trips outside the sanctuary but occasionally make trips inside the sanctuary with photographers and other non-spearfishers. The three operators are an hour to 90-minute drive from Houston. Divers beyond a reasonable driving distance can fly into Houston’s William P. Hobby Airport or George Bush International Airport just north of metropolitan Houston.

Conditions: The summer season is May through October, with mid-July to mid-September as the best time for good weather and flat seas. The winter season (when hammerhead sharks are active) is weekends only from February through April. Water temperatures vary from the high 60s°F (20°C) to lower 70s°F (23°C) in the winter and get progressively warmer in the summer from the high 70s°F (26°C) to mid-80s°F (29°C). Visibility at the East and West Flower Garden Banks ranges from 75 to 150 feet (23 to 46 meters) year-round. At Stetson Bank, visibility can be more than 100 feet (30 meter) in the summer but drops to 40 to 60 feet (12 to 18 meters) in the winter.

Currents at FGBNMS vary greatly and can change considerably during a dive, but even when there’s a swift current at the surface, swimming can be easy on the bottom. On occasion strong currents require hand-over-hand maneuvering on the surface line leading to the main downline. Gloves are good to have for descents and safety stops.

The tops of the reefs are at depths of 60 to 65 feet (18.3 to 20 meters), and typical dive profiles are 65 to 95 feet (20 to 29 meters). Since the reefs are in the open ocean up to 115 miles (185 kilometers) off the coast, divers should have intermediate or advanced skills. Safety sausages are mandatory in case of an unplanned ascent resulting in separation from the boat.

Reef health: With coral reefs declining worldwide, it’s prudent to take steps to prevent the spread of stony coral tissue loss disease that has affected Florida and the Caribbean. The sanctuary has guidelines for divers with specific gear-disinfection instructions at flowergarden.noaa.gov/protection/preventcoraldisease.html.

Explore More

See more of Flower Garden Banks in these videos and a bonus photo gallery.