A wonderland of mantas and more

WHILE THE WORLD WAS STILL MOSTLY LOCKED DOWN with travel restrictions, my social media feed was alive with gorgeous photos from the Maldives. The Maldives opened sooner than most foreign dive destinations, so there was ample photographic inspiration for our trip in May. The online coverage included the whale sharks, manta rays, tiger sharks, and colorful tropical reefs that we hoped were awaiting us.

All we had to do was get there, which was easy by exotic dive travel standards. A direct flight from Miami to Doha, Qatar, took 14 hours, and then a five-hour connection took me to the international airport in Malé, the Maldives’ capital. While that is a long time, especially factoring in the layover in Doha, it is also easy, making the Maldives more accessible than most world-class dive destinations. While Miami was convenient for me, others in our group departed from New York, Seattle, Houston, and Los Angeles. There are other U.S. and European gateways to the Maldives, which depends on tourism. Easy air access is the lubricant that keeps the wheels of commerce spinning.

From Malé, a speedboat or airplane can whisk visitors to a land-based resort on one of many white-sand-rimmed islands — there are 1,192 recorded islands in 26 atolls throughout the Maldives. As we did on this trip, you can also meet a liveaboard for one of many possible itineraries. However you do it, the dive opportunities are situated away from the capital’s congestion and amid a sea of blue. Fortunately, being away from the capital doesn’t necessarily mean a far trip — there is good diving less than a 30-minute boat ride away and throughout the archipelago.

A brief overview of the Maldives’ reef structure helps explain the dive opportunities. The Maldives feature submerged volcanic mountains, which provided the substrate for coral colonization. The low coral atolls built up atop these peaks and rising sea levels led to extensive fringing reefs. These islands are now only the very tops of submerged mountains and are in jeopardy of the sea soon (geologically speaking) subsuming them. Large apartment developments are under construction on Malé to house residents from the outer islands that are losing land, but tourism continues to thrive despite this infrastructure problem.

The diving varies according to whether you are along a channel, faru, thila, or giri. Divers generally drop in the channels between the open ocean and lagoons on an incoming tide for two reasons: It brings the blue ocean water through the channel, and an outgoing tide would sweep you into the vast ocean rather than a quiet, protected lagoon, where it’s easier and safer to reboard the dive boat.

A dive dhoni noses up to the shallow reef facing the open Indian Ocean, while a channel leads to a protected lagoon.

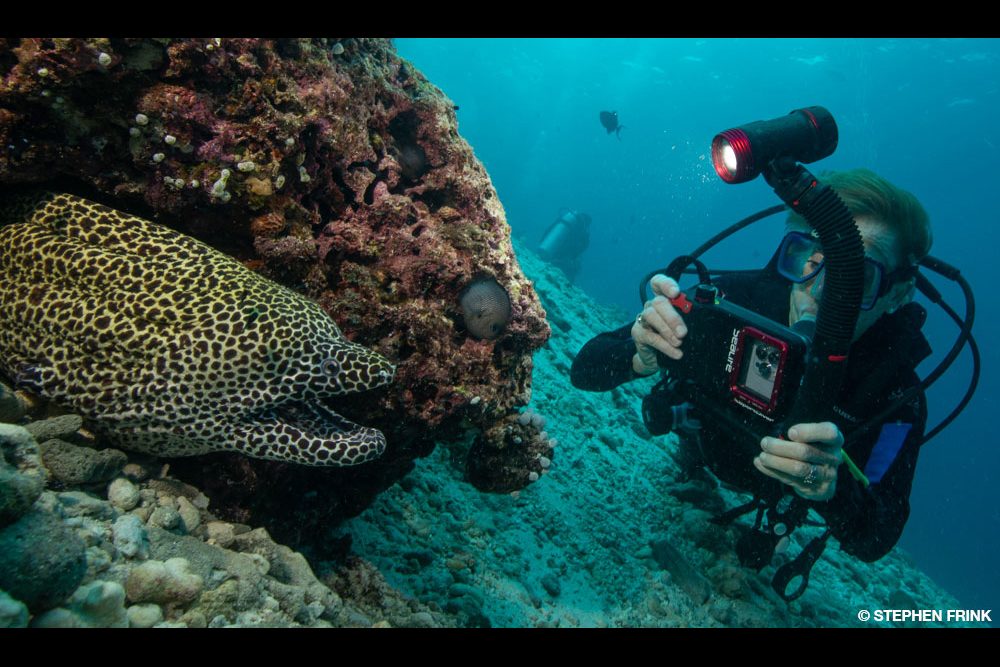

At the dive site known as Fish Tank it is common to see moray eels of different species cohabitate in the same crevices in the reef.

Farus are circular reefs rising from the seafloor, usually within a channel. The current and nutrients sweeping by with each tidal shift mean there are plenty of good farus with soft coral growth. In an optimal tide, good pelagic action happens at the current-facing point. A thila begins in shallower water inside the atolls and can be small enough to circumnavigate on a dive. The giri is often smaller, but these terms are often interchangeable. Both lack the circular structure and instead present a shallow promontory with a concentration of coral.

This is relevant because the type of diving depends on the tide, where the structure is located relative to the channel, and whether it is in an area protected from the current. Our group of photographers found some of the drift dives through the channels to be unproductive. While there were plenty of things to photograph, it was hard to stop long enough to set up the shot. We often opted for a quiet reef dive instead of a high-velocity drift. The Maldives gives you plenty of options depending on the group’s preferences.

Malé is at the southern edge of North Malé Atoll, and this area is well-explored, with dozens of quality dive sites. Beginning our expedition here let bags that did not arrive on the international flight catch up to us while we were still near the airport.

You can move much farther afield to start, and various liveaboard itineraries have evolved to support specific dive interests. A southern itinerary can increase the likelihood of shark encounters. Addu and Fuvamulah are known for tiger, guitar, thresher, hammerhead, oceanic blacktip, whale, and silvertip sharks along with oceanic and reef mantas. While that sounds exciting, we weren’t going so far south this time, but it may be the itinerary for my next visit.

The Maldives feature submerged volcanic mountains, which provided the substrate for coral colonization. The low coral atolls built up atop these peaks and rising sea levels led to extensive fringing reefs.

The country is so vast in terms of marine attractions that you can’t go wrong no matter where your liveaboard sails. The archipelago is spread over nearly 35,000 square miles, running more than 510 miles north to south and 80 miles east to west. As you move away from Malé, you can choose among popular itineraries, including Ari and Rasdhoo Atolls or perhaps Baa Atoll, which is famous for the scores of manta rays often in residence at Hanifaru Bay between July and November. Or you might head south to catch Mulaku, Vaavu, and Kolhumadulu, which is what we did on my 2016 trip to the Maldives.

Departing Malé boats can cruise a circular route either clockwise or counterclockwise. We opted for counterclockwise to stay within reach of the airport and began with Rasdhoo Madivaru. Our checkout dive helped us dial in our buoyancy and refresh dive skills grown rusty during travel restrictions. Not expecting too much, I jumped in with a 50 mm macro lens, thinking that the water clarity would be marginal, but at least there would be good fish. The fish did not disappoint, and the visibility surprised me. We had at least 80-foot clarity and 84°F water, so it was very comfortable with my 3 mm suit. I almost immediately found a large school of blue-lined snapper and one of my favorite Indo-Pacific reef dwellers, the clown triggerfish. Coral groupers and longsnout butterflyfish decorated the sloping reef, while host anemones and their resident clownfish provided willing subjects to hone our group’s somewhat neglected photo skills.

Michael Aw photographed this tiger shark in the southern islands of the Maldives.

I was surprised that our second dive would be at a manta cleaning station at North Ari Atoll because that had the potential to be a highlight of any Maldives dive holiday. I thought the crew would save the outstanding opportunities for later in the week, but our trip’s direction changed their priorities. The cleaning station was indeed spectacular, not only for the manta interaction but also for the critters we encountered while waiting for the mantas to arrive. According to our dive briefing, the prevailing tide would signal which side of a particular shallow coral bommie our group should occupy. The fish that cleaned the mantas were in residence there, so all we had to do was wait and not bum-rush the mantas when they eventually came around.

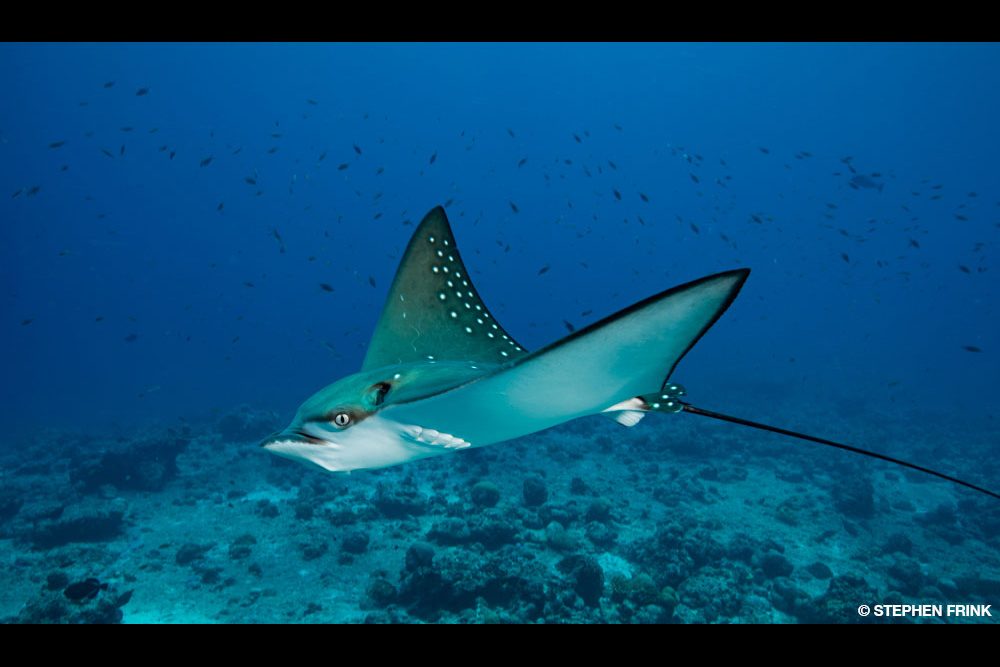

The waiting could have been tedious but for the large school of humpback red snapper at the periphery of the coral head. Our discipline to stay in place and await the action was tested when a mellow eagle ray came by and was tolerant of me swimming alongside only 2 feet away. Recognizing the farther I swam with the eagle ray, the farther I’d have to swim back to the cleaning station when the mantas came, I turned around just in time to see the mantas approaching from some place known only to them. Our group did exactly what the dive crew had told us: stay on the bottom and let the mantas come to us.

As the crew predicted, a juvenile whale shark came to dinner. It was perhaps 18 feet and definitely not going anywhere else as long as food was being served. We had all the time we wanted to snorkel with the whale shark. Hours later we went to bed with the whale shark still at the stern.

When I settled in again, one of the mantas was hovering just inches above my friend Paula Selby’s dome port. I got some great shots of the interaction from the side but was envious of Paula’s vantage point until I looked at her port extension and realized she had to be shooting a 16-35mm zoom lens. That is plenty wide for most things, but a manta belly 6 inches from the dome would be little more than a blanket of white draped from above. Still, it was a cool experience for her, and it went on like that for two full minutes. Fortunately, the manta circled back around, allowing her to get the side view.

The following two dives at Bathala Thila and Hafsa Thila required a bit of self-control because there were so many different anemones balled up with their colorful mantles exposed, and how many of those can you photograph in a lifetime? Apparently a few dozen more, judging from the folder of Maldives shots from that day. At least I shot some more clown triggerfish and blackbar soldierfish to add some variety to the day.

The night dive at Maaya Thila was an anomaly from the clear water we had earlier in the day; with the outgoing tide, the visibility couldn’t have been more than 30 feet. We tried to drop onto a pinnacle but couldn’t see it and missed the top. While getting my accidentally released surface marker buoy (SMB) reorganized, I descended steadily deeper until I found myself kneeling on the sand bottom at (yikes!) 116 feet. It goes to show that doing 6,000 dives doesn’t prevent stupid, but the deep descent did us no harm. My dive buddy and I made our way back to the pinnacle’s top at 25 feet, where we were supposed to be, and photographed marbled rays, jacks, and whitetip reef sharks.

Valerie Rutledge uses her iPhone in a SeaLife SportDiver housing to photograph soft corals at Fohtheyo Kandu.

The morning dive continued our southward trajectory to Fish Head, a dive site on Mushimasmigili Thila. It was more like Fish Soup due to a light-obliterating school of Moorish idol on the island’s current-facing point. I also had great encounters with a docile hawksbill turtle and a large school of blue-lined snapper. That’s a dive I would have revisited, but it was good because of the incoming tide, and the energy would have abated at slack tide. Better to leave that one in the memory bank and on the memory cards and move on to the next adventure, another manta ray cleaning station at Mahibadhoo Rocks.

The protocols stayed much the same, and our group got situated along the shallow reef’s downcurrent edge. On this dive, Tracey Bennett got the benefit of the manta-belly blanket dropping down on her dome port, the animal touching the dome ever-so-gently before lifting off to the reef to be cleaned.

The following day’s first dive was in a channel with a strong current passing through. During the briefing the divemaster informed us that we would drop to a rocky promontory jutting out into the blue, and with the incoming current ripping, we were to use our reef hooks to attach to a bit of rock and wait for the sharks to come to us. The catch was that this was at 90 feet, so I wouldn’t have much time, and it meant a gray reef shark might come within only 5 or 6 feet at the very nearest. I would be lucky to get more than a distant fly-by. This wasn’t going to be fodder for a world-class shark photo, so I cut loose from the reef and did the drift through the channel.

One extreme channel dive was enough for me. When it was time for the next dive, I wanted to know the options and asked the crew about what looked from topside like a sloping reef. It was a random spot they had rarely dived, but for a healthy reef and colorful reef tropicals, this turned out to be one of the best dives of the trip. The ubiquitous clown triggerfish was also here, but because the reef was so pristine, the backgrounds were awesome. I had a great series with very approachable regal angelfish before moving to longsnout butterflyfish doing what they are anatomically designed to do: poke inside tiny coral fissures to feed.

The country is so vast in terms of marine attractions that you can’t go wrong no matter where your liveaboard sails. The archipelago is spread over nearly 35,000 square miles, running more than 510 miles north to south and 80 miles east to west.

That night we were treated to one of the highlights of a Maldives adventure — a whale shark at night. Whale sharks are a highlight of South Ari Atoll, particularly during the northeast monsoon season from December to May. As dusk approached, the crew turned on a powerful quartz halogen light mounted to the swim platform at the boat’s stern. The light attracted tiny shrimp and plankton as the twilight gave way to black. As the crew predicted, a juvenile whale shark came to dinner. It was perhaps 18 feet and definitely not going anywhere else as long as food was being served. We had all the time we wanted to snorkel with the whale shark. Hours later we went to bed with the whale shark still at the stern. I don’t know what happened when they turned out the light, but I assume the food chain quickly snapped, and that was the end of it until the next night’s visit from another liveaboard.

The next morning brought us yet another manta cleaning station at Kurali Manta Point. Douglas Seifert reported in a 2018 article in Dive magazine that the Maldives is home to “the world’s largest population of reef manta rays. Estimates of the total population of manta rays in the Maldives are said to be as high as 10,000 individuals; some believe the figure could be double that.” That was four years ago, but I saw nothing to dispute the claim. This dive was also productive, with the entire group following orders to hold in one position, and our reward was mellow mantas happy to be in proximity and get cleaned.

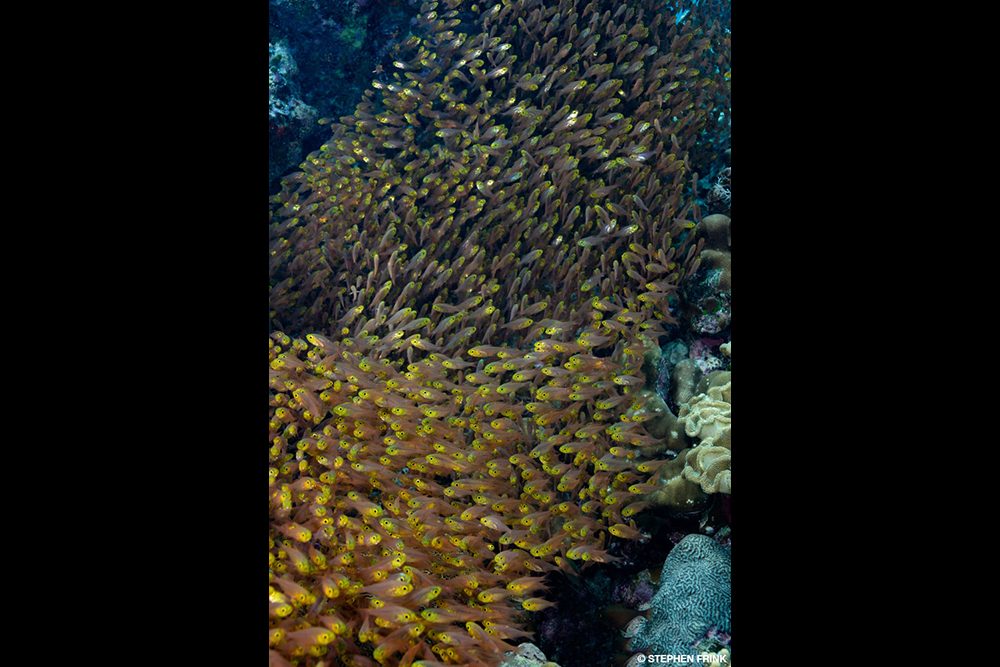

Other trip highlights include the pristine shallow hard coral garden at Hakura Thila and the school of redtail butterflyfish at Vanhuravalhi Kandu. By this time in the trip I was noticing a curious paucity of soft coral, and to scratch that itch our dive staff suggested Fohtheyo Kandu. It was better in that regard than some of the predominantly hard coral reefs we dived earlier in the week, but we weren’t seeing anything that compared to Fiji, Raja Ampat, or the Red Sea in the soft coral department. I don’t doubt some parts of the Maldives have more soft coral than we saw, but overall it wasn’t a big feature of our itinerary.

One of the best dives of the trip was on the last morning. Some of our group chose to sit out to offgas, although we had more than 24 hours between the dive and our flight. We had returned to anchor just off Malé, and there is a dive called Fish Tank that originated with local restaurants dumping their fish carcasses off the dock. As the dive evolved into a productive site, local snorkel and dive boats would often chum the water as a piscine enticement. The most noticeable beneficiaries of this largesse are the moray eels. Countless morays are in nooks and crevices along the bottom, and it is common to see two or three species of eels cohabitating in a single reef recess. It was so good there I dived it twice, once with a 16-35mm wide-angle lens to capture the large school of Moorish idols and models posing before immense honeycomb morays, and later with a 50mm macro lens to take advantage of all the easy fish portraits.

Currently, there are 33 marine protected areas throughout the Maldives, an indication that the government is cognizant of the value the coral reef and their significant megafauna (whale sharks, manta rays, and sharks) contributes to the national economy by attracting dive tourism. They may not be able to do much to influence climate change and rising seas. Still, they can enhance their marine resources’ quality, and the government and the Maldivian dive industry are committed to doing just that. AD

HOW TO DIVE IT

Diving season: The prime dive season is from December to May, although diving is now pretty much year-round. A northeast monsoon arrives around late December and brings calmer water to most of the archipelago. In the clearest conditions, you can have visibility in excess of 100 feet, but tidal movements can reduce it. Incoming tides bring clear water, but outgoing tides carry sediment from the lagoon and sometimes decrease visibility on the fringing reef.

Dhoni diving: Most liveaboards operate synergistically with a dhoni — a 50- to 60-foot yacht with diesel engines and a compressor on board (usually for air and nitrox). Sleeping and dining happen on the mothership, but diving is from the dhoni. This isolates the fill station noise to the dhoni, which also has a stable platform with a sturdy ladder for getting back onto the boat.

Currents: Diving in currents is a fact of life in the Maldives, although your dive staff can choose reefs devoid of currents or opt for the high-voltage drifts through the passes. It is possible to surface far from the dhoni, so each diver should travel with a delayed surface marker buoy and be skilled in deploying it.

Depth: Maldives law restricts dives to 98 feet (30 meters). There is no reason to go deeper, given the topography of the reefs and passes.

Temperature: Expect air temperatures in the 80s°F and water temperatures of 80°F to 86°F. I’ve found that a 3 mm wetsuit is comfortable year-round.

Passports and documentation: Check the current information on passports and entry requirements at travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/international-travel/International-Travel-Country-Information-Pages/Maldives.html. Current travel restrictions and COVID-19 policies are available at visitmaldives.com/en/covid19-updates.

EXPLORE MORE

See more of marvelous Maldives in a bonus photo gallery and this video.