Editor’s note: Stan Waterman passed away on August 10, 2023, at his home in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, with his wife of 73 years, Susy Waterman, close by.

EVEN THOUGH I WAS A photojournalist for Skin Diver magazine for 17 years, one of the covers I most remember was not one I shot but a portrait of Stan Waterman that Geri Murphy took for the September 1982 issue.

I hadn’t met Waterman at the time, but there he was — tanned and smiling, with a gold Rolex Submariner on his wrist, and colorfully coordinated with his orange Scubapro stabilizing jacket, red-rimmed mask, and well-worn orange 16mm movie housing with a Sekonic L-164 light meter mounted atop the optical viewfinder. The headline was “Diving’s Poet Laureate,” but to me he was the consummate vision of an itinerate cinematographer.

His story has been well-told over the years. Two of my favorite biographies are “A Life Overboard” from the May/June 2005 issue of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine (where Waterman graduated in 1950) and his interview in Bret Gilliam’s 2007 book Diving Pioneers and Innovators. Both focus on a single life-altering event, one Waterman highlighted to me as well.

He was enjoying the Christmas 1934 holiday with his family in Palm Beach, Florida. A souvenir was under the Christmas tree from a family friend who had just returned from Asia: a diver’s mask of the type used by the ama, women breath-hold divers who harvested Japan’s seabed.

Waterman swam along the shallow reefs and jetties off the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach, looking underwater before facemasks were readily available.

“I dived down, opened my eyes, and was hooked for the rest of my life,” he said. “I was 11 years old then, but it is still so fresh in my memory that it could have been yesterday.”

Waterman was born in New York City in 1923 and grew up in Montclair, New Jersey. After his parents divorced, Waterman’s childhood summers were divided between his mom’s house in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, and his father’s summer home on a peninsula on Penobscot Bay in Maine. Maine was about tidal pools and sailing; Delaware was bodysurfing with his friends. Either way, it was about the sea, even as cold as it was.

He joined the Navy during World War II and was stationed in the Panama Canal Zone, which meant the ocean was still nearby. He and his buddies loaded up their motorcycle sidecars with pole spears, masks, and fins and would dive in and spear almost anything that moved.

After the war he enrolled at Dartmouth, majoring in English and focusing on Shakespeare. One of his instructors was Robert Frost, which may have inspired the ”poet laureate” headline so many years later. His summer romance with Susy eclipsed the significance of anything he learned in school. They married two weeks after college graduation and raised three children over their 73 years together. They initially moved into the family house in Maine to farm blueberries. That wasn’t as outlandish as it seemed — at the time blueberry farming was one of Maine’s three primary industries alongside lobster and lumber.

It was dry and dull work, but the allure of the sea was all around. U.S. Divers started around that time and sold the Aqua-Lung. Waterman bought the 25th unit in the U.S. and likely the first in Maine. He was the go-to guy for scuba in Maine in 1952 with his wetsuit and portable compressor. He recovered scallop drags, cleared fouled props, and even found some expensive rifles that some hunters lost when they capsized their canoe. The Aqua-Lung’s instructions said, “Don’t come up too fast,” which is still good advice.

Around this time Jacques Cousteau was having his own adventures, including making movies 150 feet underwater in the Red Sea. Cousteau’s account of these adventures, The Silent World, inspired Waterman to seek horizons beyond the blueberry farm.

Hometown: Divided between Penobscot Bay, Maine, and Princeton, New Jersey

Age: 100

Years Diving: 80

Why I’m a DAN Member: If you are a seasoned diver or want to be one, do yourself a favor and join DAN before you buy another snorkel. It will help you be educated, informed, and safe until you hang up your fins at age 90, as I did a decade ago. Even now, I keep in touch with the dive world by reading Alert Diver.

He wanted to travel to the Bahamas. He needed a wide-beamed and seaworthy boat, and Maine was awash in those. He took out a second mortgage on the house and bought a 40-footer he named Zingaro. With that, he headed south to Nassau, and by 1954 he had established the first liveaboard dive boat in the Bahamas.

The dive business barely broke even, but it was enough to keep him on the water and shooting 16mm film with an early Fenjohn housing. He eventually amassed enough footage to edit his first film, Water World.

He went on a show circuit that typically ran from the fall through April, visiting small-town venues and projecting his self-narrated films for $125 per show. He did 162 speaking dates in one year at his peak and eventually had three agents booking for him and a rate of $350 for a show.

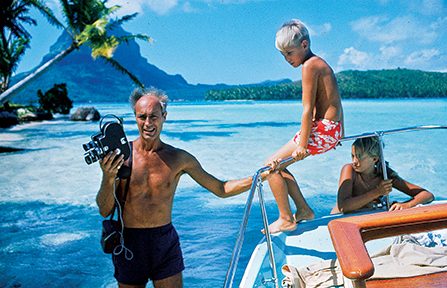

Between shooting in the Bahamas and being on the road, life was full for Susy at home with their children Gordy, Susy, and Gar. Maine was too isolated, and they wanted better schools for the kids, so they moved to Princeton, New Jersey, which is still their primary residence. A more urban home did not necessarily mean fewer adventures. On the contrary, the Watermans wanted family experiences while the children were still young. One of their higher-profile adventures in the early 1960s was what they call the “Tahiti year.” Stan had been to Tahiti twice on assignment and had enough contacts to plan the logistics of spending a year on location. He obtained some sponsorship from National Geographic and a commitment from PBS for an hour-long television special.

I had heard Waterman suffered decompression sickness (DCS) on that expedition. I’ve had DCS a few times, but I could always reach out to Divers Alert Network, so I was interested in what happened to him in the years before DAN existed. With time, the incident didn’t resonate as a big deal to him, but Susy remembered it as being more dire.

Waterman got DCS the same way as many other image-makers who wanted just one more shot. Susy said that he stayed down too long and came up too fast and then had confusion and a loss of motor skills. He spent two days in the French recompression chamber in Papeete. Susy said it took some time for his legs to function normally, but he had no residual complications, and it didn’t affect his diving after that.

His résumé lists several significant film projects, but for sheer audacity nothing can eclipse Blue Water, White Death. The premise was to bring home the first underwater film of great white sharks, about which we knew very little back then. Waterman and his friend Peter Gimbel, one of the directors, discussed a concept in 1964 during Maine summer evenings by the fire. With Waterman off for his Tahiti year, it fell to Gimbel to assemble a budget and a team, which included Jim Lipscomb for topside camera and the underwater crew of Waterman and Australian filmmakers Ron and Valerie Taylor.

Their first stop was South Africa because the Union Whaling Co. told them about swarms of great white sharks that attacked the whales before the crew could retrieve them to the boat. The area had plenty of sharks, but they were oceanic whitetip sharks, not Carcharodon carcharias. When no one knew much about oceanic whitetips, however, it was bold for Gimbel, Waterman, and the Taylors to leave the safety of their cages at night to get better shots of them. As for the great whites, the filmmakers got the footage they needed in South Australia with the help of the world’s most famous great white shark attack survivor, Rodney Fox.

Waterman’s career was replete with other projects that kept him at the top. He became dear friends with Peter Benchley after Benchley moved to Princeton following the publication of Jaws. They had many adventures together working for the ABC show American Sportsman. That led to Waterman and Chuck Nicklin being camera operators for the Hollywood feature The Deep, with Al Giddings as the director of underwater photography. The 1977 film, an adaptation of Benchley’s novel of the same title, starred Jacqueline Bisset, Nick Nolte, and Robert Shaw, along with the largest and most ferocious green moray the world has ever known — animatronic, of course.

Instead of dwelling on these high-profile and significant film projects while recounting his career, Waterman became most animated when speaking of the Aggressor liveaboard tours he led. It was only in a later conversation with Anne Hasson of Aggressor Adventures that I understood his commitment and the time he’d invested.

Between 2000 and 2013, Waterman traveled on 46 Aggressor liveaboard charters. Susy said those years were so special to him because he could go out and shoot. Being underwater with his camera and a subject fueled his passion all those years. The social aspect of being on the boat and entertaining guests with his stories and films was also meaningful. But it was all about the shooting.

Waterman is now 100 years old. You don’t get to be 100 without some physical impairment. Tragically, a man who lived a life defined by his personal vision has essentially lost his sight. Yet chatting with him on the phone is both familiar and delightful. His mellifluous voice sounds the same as it has on the many stages where he presented his films to enraptured audiences, and the pure joy he exudes as he eloquently recounts a life so well-lived is uniquely Stan.

September 1, 2013, is a date I can’t forget because it is in the metadata of the underwater photos I shot that day and also because it was during Waterman’s final dive trip. We were together with other guests on the Cayman Aggressor IV to celebrate Waterman’s 90th year of life and his decision that he was finally ready to abandon his life aquatic.

We were on Little Cayman’s Bloody Bay Wall, shooting from opposite sides of the same friendly Nassau grouper — Waterman with his digital video camera and me with my stills system. I paused and backed off, leaving him alone, once again communing with cooperative marine life and in the zone.

At that moment, I imagine he wasn’t feeling 90 years old. He wasn’t thinking about being on one of his last dives. He was drawing on a life of intuitive technical wizardry, knowledge of the physics of water, and instinctive composition to bring home the shot once again, as always. AD

© Alert Diver — Q3 2023