Defining Dive Photojournalism

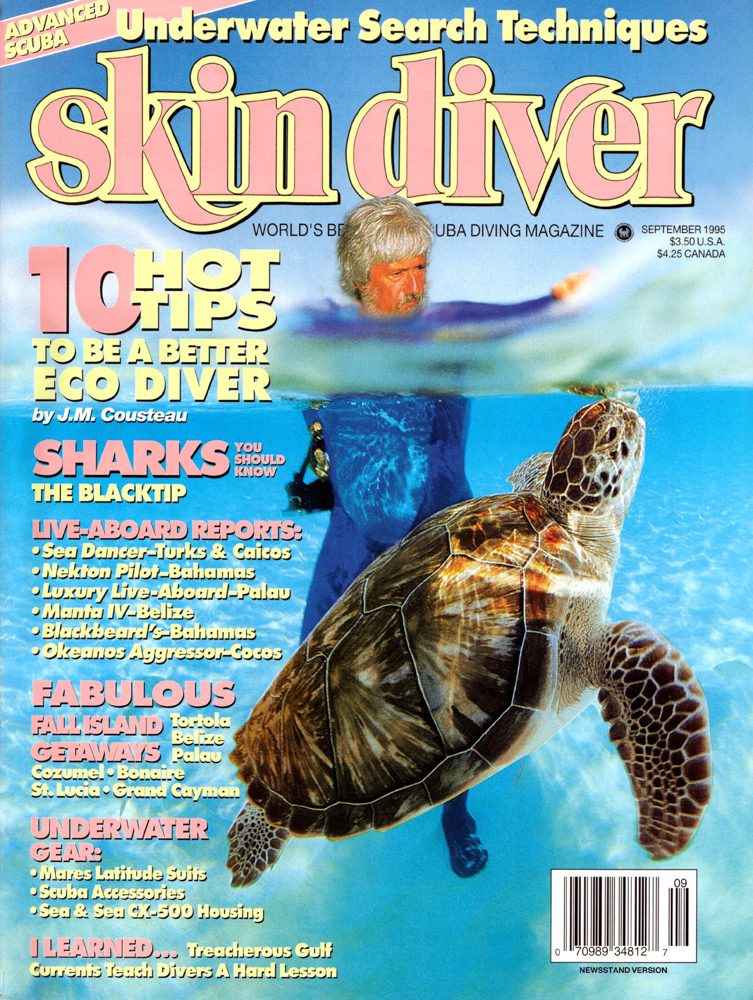

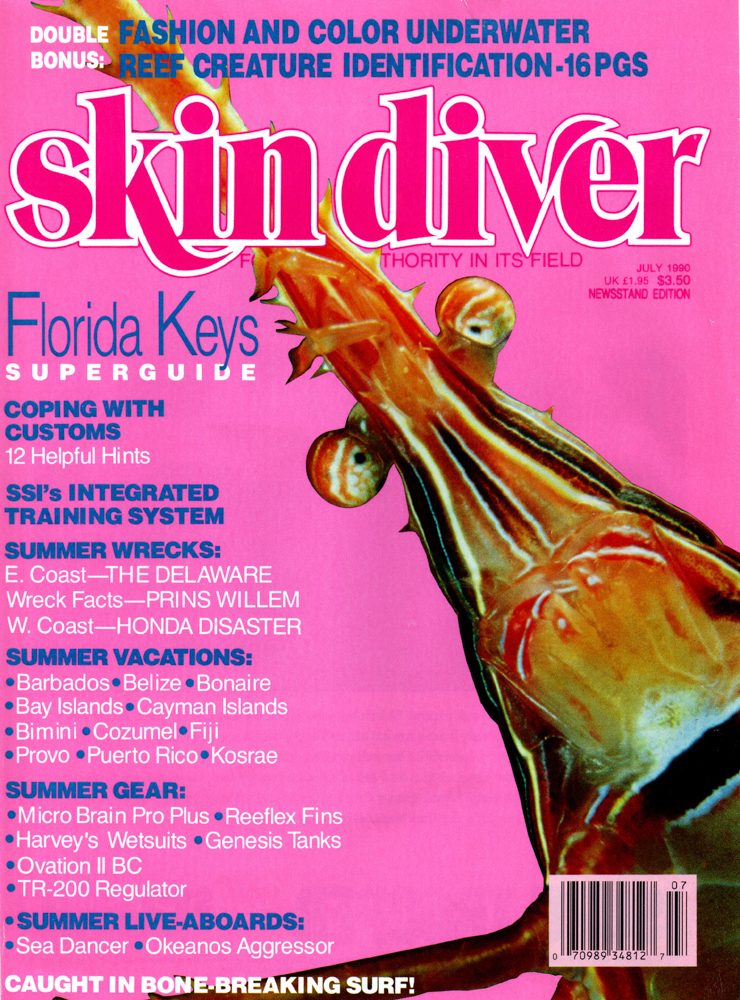

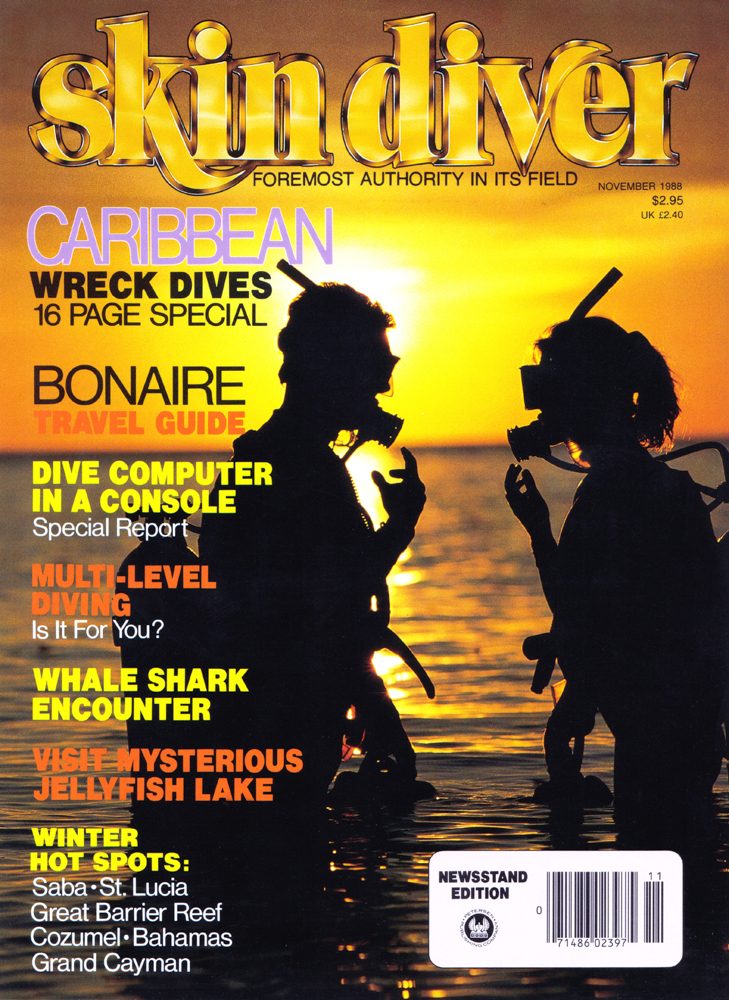

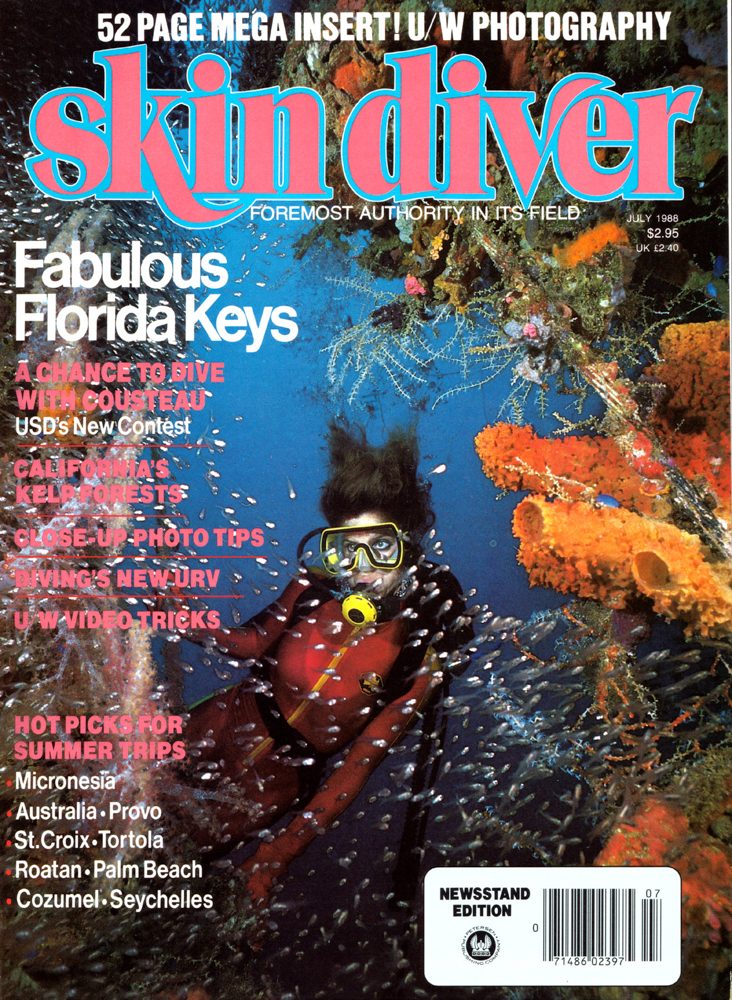

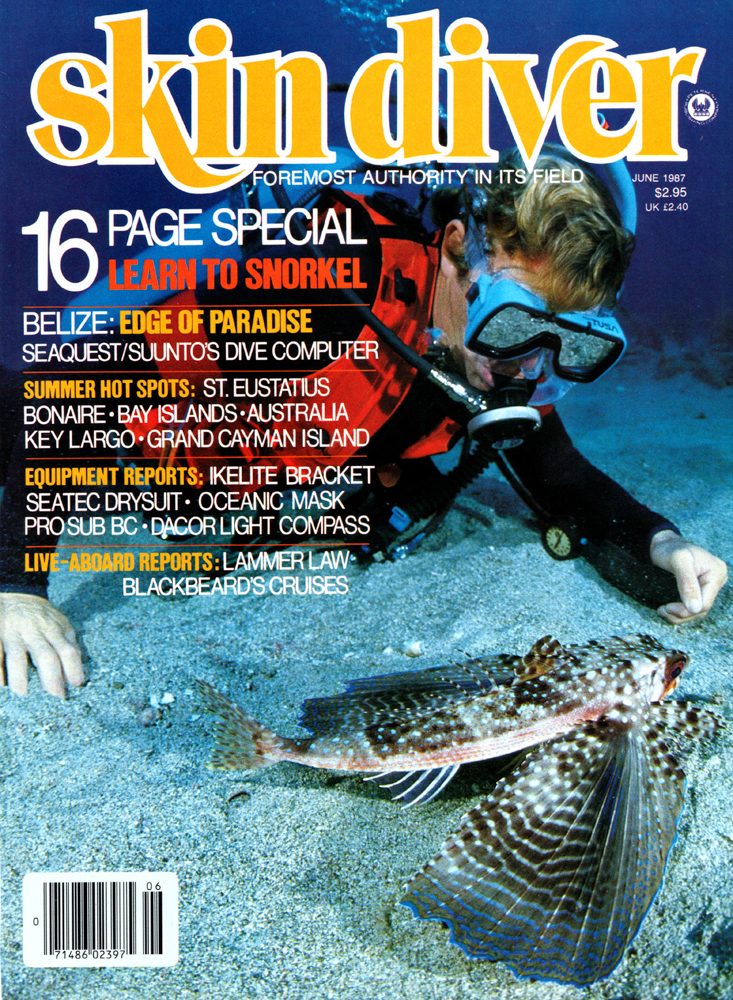

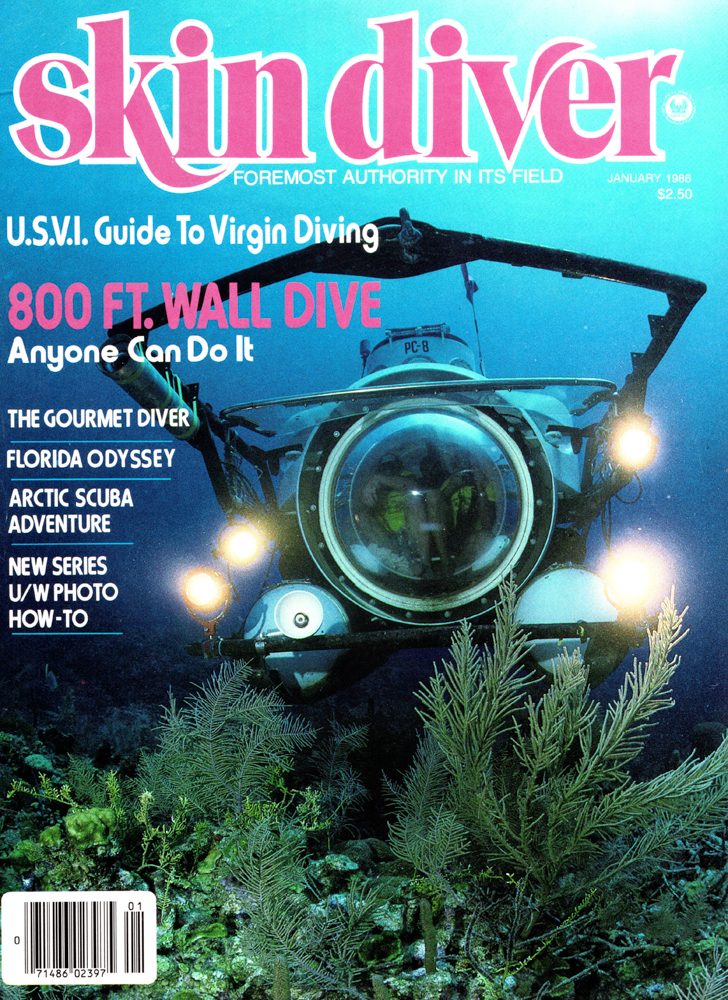

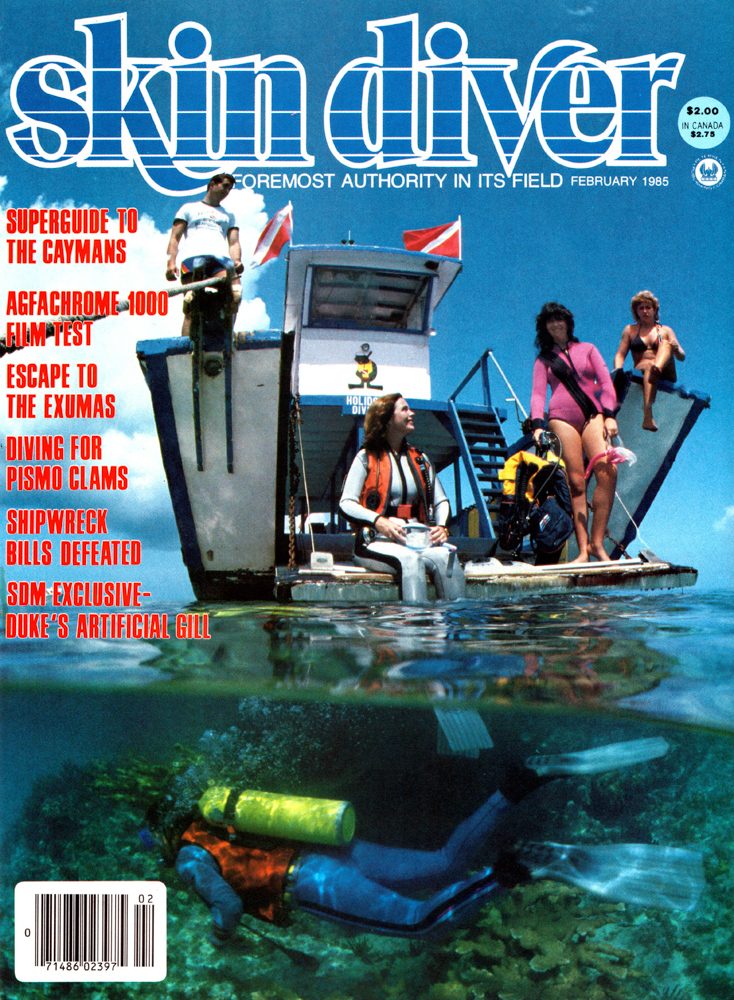

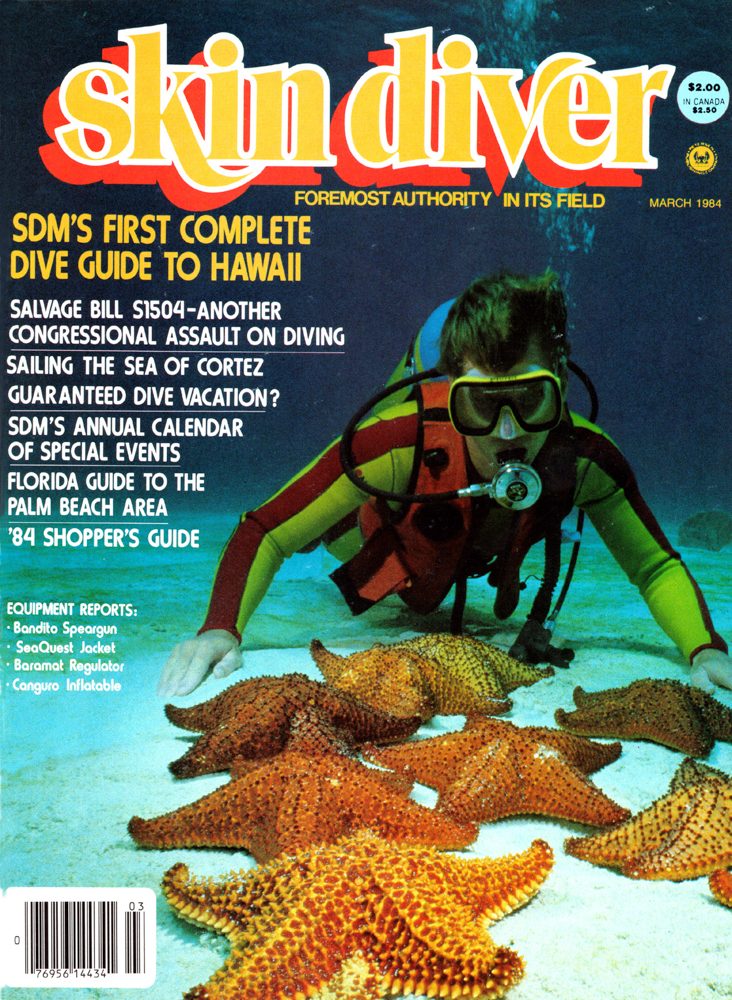

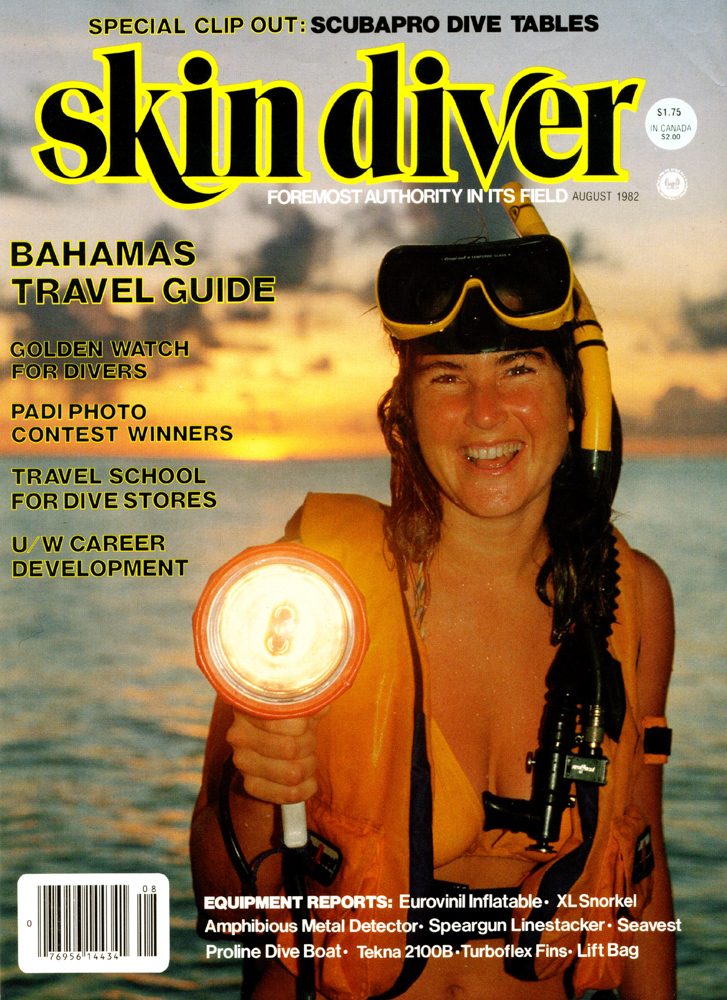

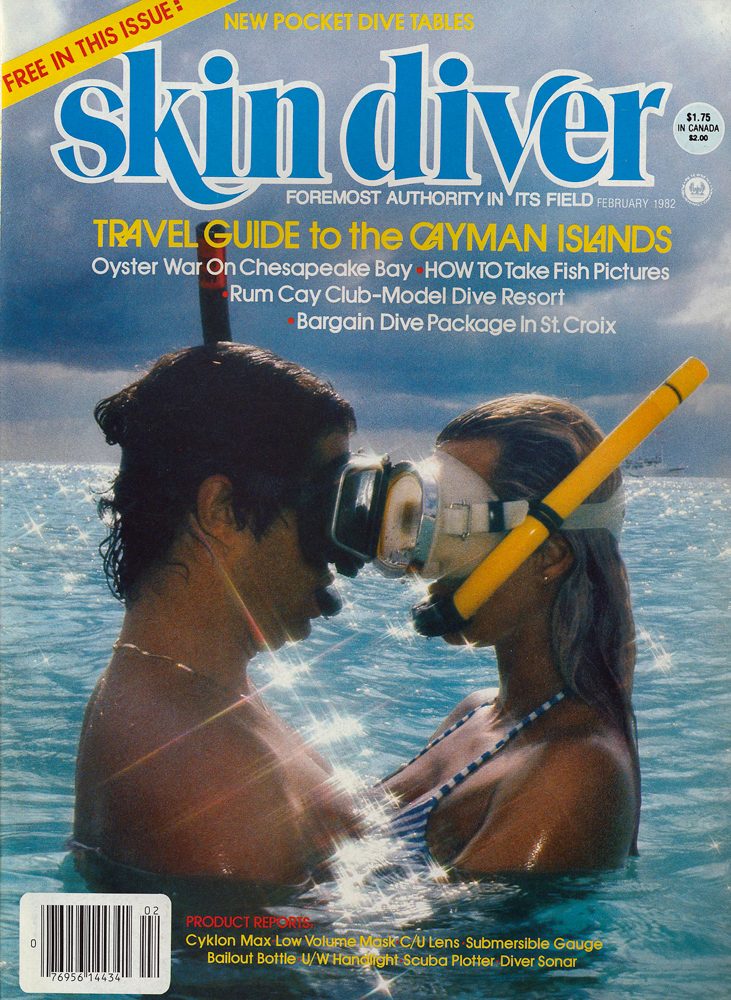

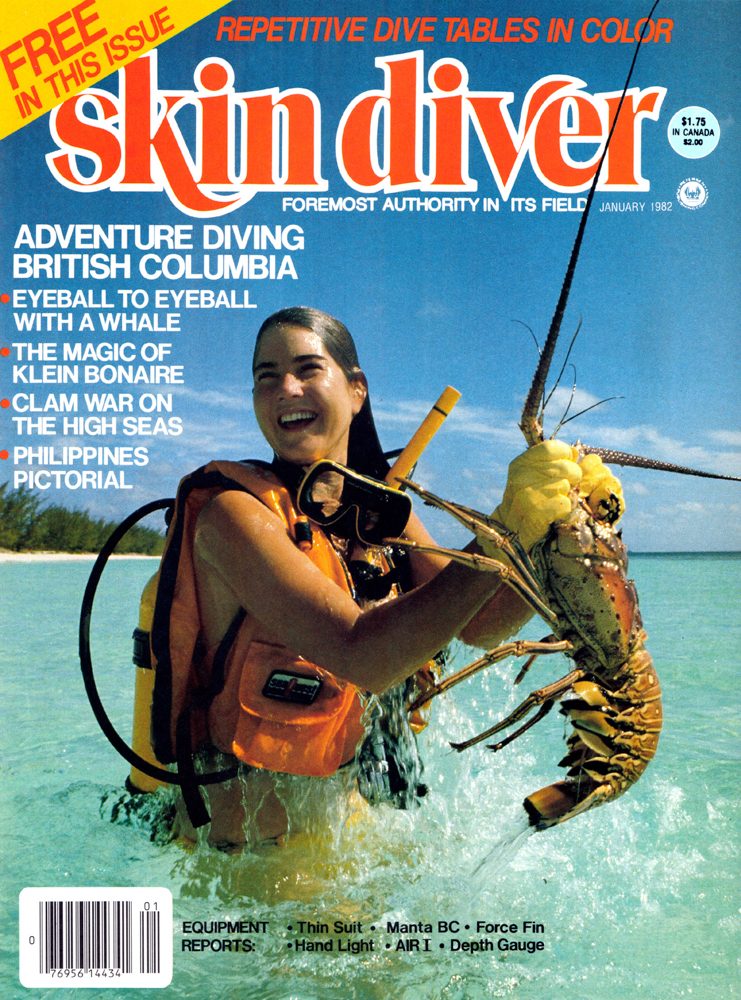

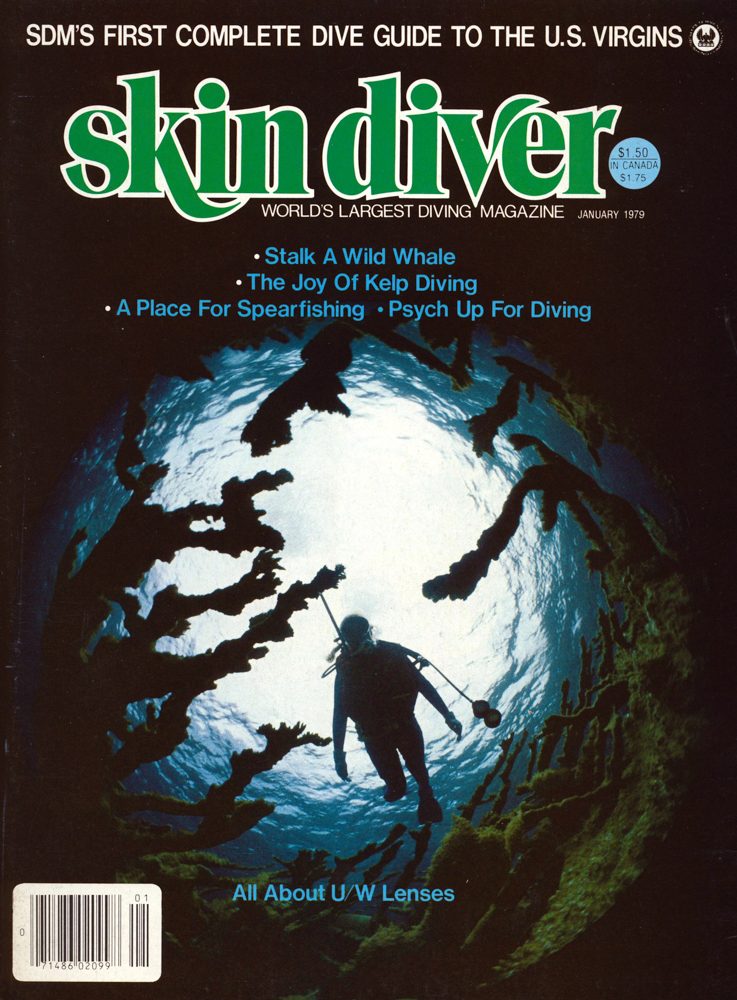

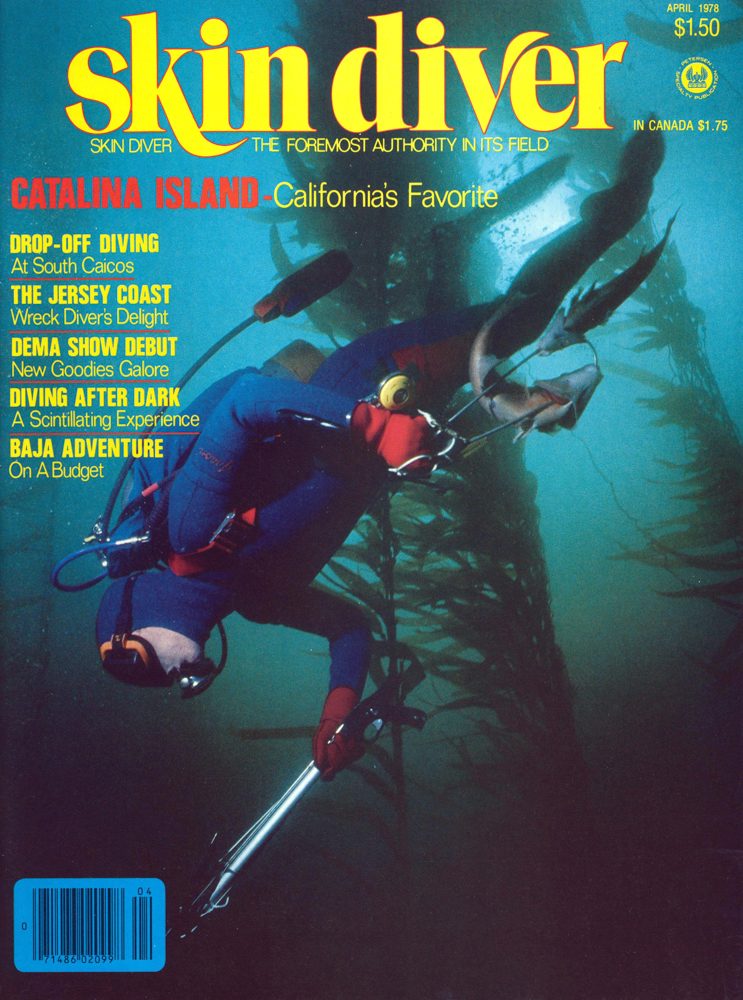

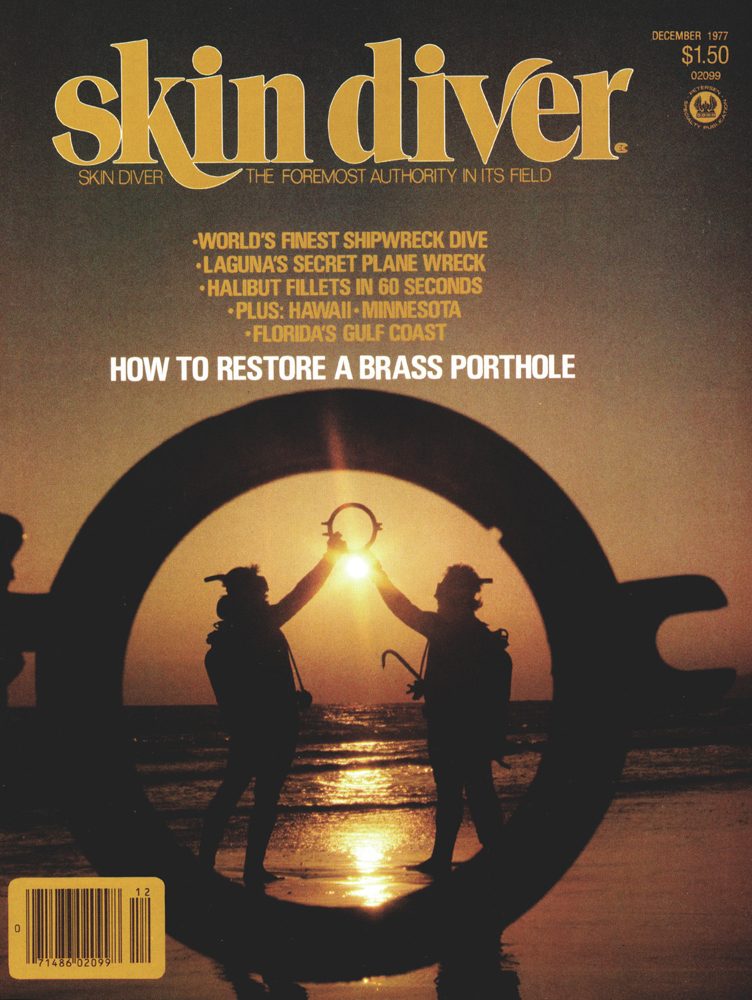

BEFORE THE INTERNET WAS AVAILABLE, people read print magazines to learn about scuba diving — how to do it, what gear to buy, and where to go. For 51 years, from 1951 to 2002, the king of the genre was Skin Diver magazine. The undisputed queen of cover photography for Skin Diver was Geri Murphy.

She had an incredible 170 cover images for Skin Diver and was frequently published in Sport Diver, PADI’s Undersea Journal, Islands Magazine, and National Geographic books. She has received numerous awards and honors, including the NOGI Award for the Arts from the Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences and induction into both the Women Divers Hall of Fame and International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame.

I knew about Murphy long before we met. The first endorsement I heard of her bona fides had nothing to do with photography but the acknowledgment that she was a New Jersey wreck diver. Her recollections of those years were the springboard for our recent reunion conversation.

Geri prepares her camera rig before diving in the Solomon Islands.

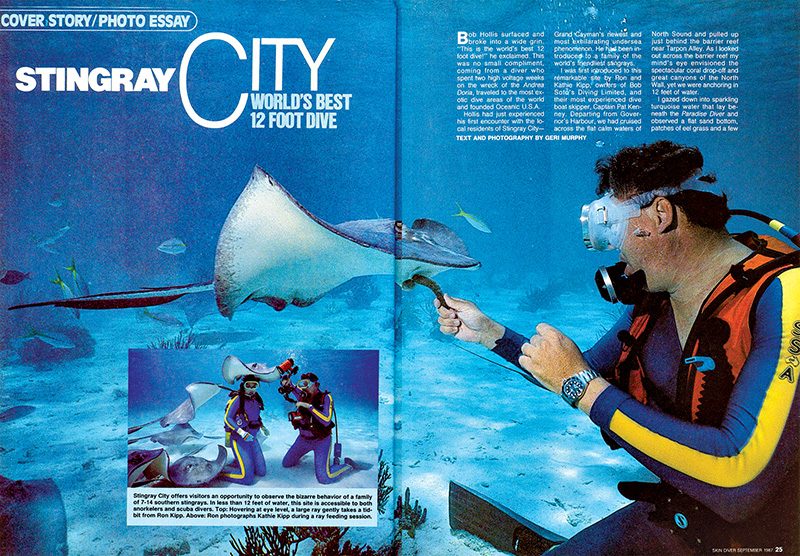

While motoring into Grand Cayman’s North Sound after a dive on Tarpon Alley in 1986, we noticed a large congregation of stingrays below us. The crystal-clear water was only 12- to 15-feet deep in the shallows, so we stopped and observed them, thinking it was unusual for so many stingrays to be in one area. We returned the next day to see if we could hand-feed the rays and photograph them. In a brief few seconds a large ray ascended from the bottom and dropped its small trap-door mouth to scoop the small baitfish Ron Kipp was holding. I pulled the trigger at that precise second and saw the strobes light the stingray’s underside. With its mouth agape and Ron’s colorful gear, I knew I had the money shot. Naturally, it was the last frame using a Nikonos film camera and 15mm lens. When I got back on the boat, I declared, “It is like Stingray City down there!” That’s what the area came to be known through the pages of Skin Diver magazine and beyond.

Murphy had an incredible 170 cover images for Skin Diver and was frequently published in Sport Diver, PADI’s Undersea Journal, Islands Magazine, and National Geographic books.

I don’t know what it means to be a New Jersey wreck diver, but I know it defined your entry into the dive world. Tell me about those days.

I was passionate about scuba diving before I ever put my head underwater. I watched every episode of Sea Hunt and bought a scuba tank with my first paycheck. We lived outside of Philadelphia, but my grandparents had a house on the beach in Ocean City, New Jersey, where I’d pretend I was Mike Nelson and try unsuccessfully to breathe air underwater through a garden hose.

I wanted to start diving while in grade school but had to wait because I needed the car keys to get to the YMCA. Once I was old enough to drive, I was all in. By 1968 I was a certified diver and a member of two Pennsylvania dive clubs — scuba was my life. I became a YMCA instructor in 1969 and received NAUI and PADI instructor certifications in 1970.

There were no dive boats back then. The fishing boat captains knew where the wrecks were, so we chartered their boats to go diving. I spent eight years exploring shipwrecks off the East Coast, logging 250 dives on 35 different wrecks. The water was cold, and in 1968 our gear was rather crude. We’d wear 3/8-inch wetsuits and weight ourselves so that with the suit compression we’d be buoyancy neutral at 90 feet: 15 pounds was the average, which of course meant we’d bob like a cork at the surface.

To compensate, we all used a deco upreel. We’d tie off to the wreck and pay out line as we ascended, so when we were at our 15-foot decompression stop we were tethered to the bottom to hold us in place long enough to offgas. Without this method, ascents would be out of control.

The high point of those experiences was when I discovered and raised a bronze engine telegraph by myself from the wreck of the Varanger, resting in 140 feet of water 28 miles off the Jersey Shore.

Great white shark diving off Guadalupe Island, Mexico, is always a thrill as well as a waiting game. We could sit in the cages for hours in cold water, and no sharks would come. But when they do, oh boy! A head-on shark shot is hardest because they tend to swim lateral to you. Luckily for me, this shark came head-on to my cage. I framed him as he passed another cage and headed toward us.

I’m a warmwater diver, so that sounds pretty extreme.

I guess so. We had to be very self-reliant to survive. When it comes to New Jersey wreck diving, you have three choices: get very good very quickly, quit, or die. Not dying was not making a living, so after high school I went to business school for one year and then went to work for General Electric’s Space Division as an executive secretary. I was very good at what I did, which allowed me some latitude to take time off and go scuba diving.

By the end of 1970 the Beach Boys were big, and California beckoned. With $100 in my pocket, I drove across the country to San Francisco. When I arrived I went to a phone booth, flipped through the Yellow Pages, and fed dimes into the slot until I had a job. I had office skills and dive skills, so I called Bamboo Reef, a dive shop Al Giddings owned. I got lucky and had a job there for four months while their secretary was out on maternity leave.

In 1973 I crossed paths with Giddings again in Bonaire. I had heard through the island grapevine that Cornel Wilde was going to shoot a movie there, so I snagged a job as assistant dive coordinator and safety diver for Sharks’ Treasure. Giddings was the underwater cinematographer, and he got to know me then as a diver to a greater extent than as a secretary.

By 1975 I was in Bonaire full time as the first female scuba instructor and underwater photography professional for Captain Don Stewart. During my first week on the job, Paul Tzimoulis, the publisher of Skin Diver, came to do a story. It was love at first sight for both of us, from the day we met until the day he died. I quickly learned to be his dive model, which was good experience for me as a photographer to later direct dive models.

In the 1980s we used food to shoot fish interactions with divers. We do not like to use fish bait because it is smelly and messy, and it clouds the water. Plus we didn’t have digital options such as Photoshop to erase an errant bit of bait from the shot. One day, for lack of anything else on board, I decided to offer some sliced apples to the angelfish, and they liked it! The fish would come right up to my face and try to feed on the apple wedge. Kathie Kipp volunteered to be the model. Using a Nikonos V with a 35mm lens and close-Up kit, I filled the target frame with Kathie’s face, and then an elegant gray angelfish swam in to eat the apple, which was held just a few inches outside the frame of the shot.

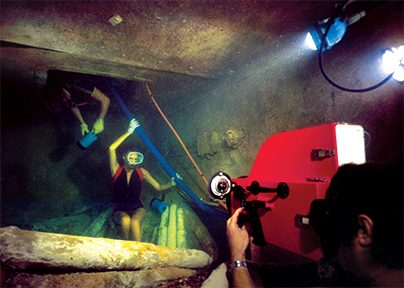

In 1988 Paul and I were diving with Stephen Frink and his wife, Barbara Doernbach, on a liveaboard in Chuuk Lagoon. We had made a dive on the Rio de Janeiro Maru early in the day and found that the minnows had just hatched beside a colorful part of the wreck. We needed a model to pose behind the new hatchlings and asked Barbara if she would do it. Stephen usually had Barbara pose for his photos, so this left him without a model for the dive. So Paul, with the great chutzpah for which he was known, asked Stephen, “Since you don’t have a model for this dive, can we borrow your camera rig and strobes?” With great kindness, Stephen consented, and the result is one of the best Chuuk Lagoon shots I have ever taken. Barbara did an awesome job positioning herself with the fish, and Paul nailed lighting the scene.

I saw my first pygmy seahorse in Indonesia in 2005, and it became my quest to get the perfect close-up shot of one. I made many trips to Indonesia and finally achieved that goal.

One of the most important Hollywood films tied to diving was The Deep. Al Giddings, Stan Waterman, and Chuck Nicklin were cinematographers, but I know you were involved as well.

I was the underwater script supervisor and was in charge of continuity. Imagine you had a shot filmed on the wreck of the Rhone with Nick Nolte and Jacqueline Bisset swimming into a wreck. They had certain dive gear and held their lights in a particular hand. Three months later on a set in Bermuda, when filming resumed showing them swimming into ostensibly the same wreck, I’m the one who made sure the visual continuity made sense.

In the late 1970s a dive shop in Cairns, Australia, offered a one-day trip to the famous Cod Hole dive site on the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef via seaplane as an alternative to the long liveaboard trips. The 150-mile flight at an altitude of 350 feet allowed us to reach the site in 2.5 hours instead of spending a full day traveling there via liveaboard.

It felt like the birth of the dive travel industry was when you and Paul were a couple and traveling together for Skin Diver. I asked Neal Watson, Spencer Slate, Stuart Cove, and Peter Hughes what it was like to have a Skin Diver feature written about them. They all said it had made their year. Watson said they hired more phone operators 30 days before the article hit because they knew they would be slammed.

Paul was a force of nature. He conceived annual destination travel guides that told readers everything they needed to know to plan a vacation. The big guys who advertised got bigger as a result. All dive operators, no matter how small, were included in the guide, even if they had only one boat and one employee.

When you think about the huge dive destinations of the 1980s and ’90s — Cozumel, Bahamas, Florida Keys, U.S. Virgin Islands, and of course the Cayman Islands — it all grew from Paul’s imagination and sheer will. We even had our wedding reception on Grand Cayman in 1986. Wayne Hasson pulled the Cayman Aggressor up to Ron Kipp’s dock after the party, and we took all the guests for a week to go diving. Those were the times of our lives. AD

Explore More

Learn more about Geri Murphy in this video, and see more of her work in a bonus photo gallery.

© Alert Diver — Q4 2023