Diving into a simulated emergency at Aquarius Reef Base

My phone’s alarm filled the air, but I was already awake. It was the day I had eagerly anticipated since first learning about the Florida International University (FIU) Introduction to Saturation Diving: Aquarius Operations and Benefits to Science course — the emergency simulation.

After completing the eight-week remote-learning program, I was one of five students selected to participate in person at the Aquarius Reef Base facility in Islamorada, Florida. Today’s emergency simulation would not be an ordinary training exercise. We would be 45 feet (13.7 meters) underwater in the Aquarius Reef Base habitat. Our mission was to navigate a surprise emergency scenario — one of several we had been practicing — and evacuate from the habitat to a mobile hyperbaric chamber on a boat. Upon reaching land, we would practice the transfer to a land-based chamber.

This practice situation wasn’t my first simulated extreme environment emergency scenario. Earlier in my career I supported NASA’s International Space Station (ISS) and Space Shuttle programs. As an extravehicular activity flight controller within the Mission Control Center team, I regularly practiced Joint Expedited Undocking and Separation scenarios. These exercises simulated situations involving pressure loss, fire, or a contaminated atmosphere, all of which required swift and precise responses by the astronauts. The extreme space environment demands meticulous attention to detail, as even the smallest deviation from protocol could have dire consequences.

The crucial difference in this underwater simulation was that I would role-play an Aquarius habitat technician. I had taken time off from work and invested money to meet, learn, and train with the legendary Aquarius operations team. Even NASA, an organization with its fair share of legends, respected the Aquarius team’s expertise.

Each student on our team had a unique connection to human spaceflight, and we were eager to learn more about the comparable characteristics of underwater living. Sergey, an amateur underwater videographer and photographer and former biomedical engineer flight controller at NASA, drove from the Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida, where he is a life support engineer who had been testing the Orion spacecraft’s life support system for the Artemis II mission. Elias is part of the team designing the next Canadian robotic arm for NASA’s Gateway Program. Judah, from the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, has a background in geology and field medicine and serves in the U.S. Air Force Reserve. Matt is from Poland and is building an underwater habitat for human spaceflight training — he would leave for the Arctic the day after our class ended. My current role involves training and operations for a new class of spacesuits for microgravity and partial gravity environments. I spend my free time flying seaplanes, volunteering as a coral restoration diver, and giving talks about science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) topics. Naturally, we are all divers.

Having spent years studying the designs of spacesuits, space stations, shuttles, lunar landers, and lunar rovers, I was particularly fascinated by sustainability. In some ways it is easy to design and build something new; the real challenge often lies in sustainment and operations. Maintaining a habitable environment in harsh conditions is a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance. The ocean floor’s extreme pressures and corrosive environment present one of the most formidable challenges to human habitation.

I had been diligently compiling questions for the Aquarius operations team since the program started. Minor equipment failures — an O-ring unexpectedly giving out or a plastic component breaking due to cycle failures — are familiar to us as divers. But I wanted to delve deeper and understand the intricacies of Aquarius’ long-term operation.

We had the opportunity to review maintenance logs and seek insights into early failures, key preventative measures, and

seemingly indestructible components that had defied the odds. The Aquarius operations team, with their decades of experience, held the secrets to this remarkable underwater habitat’s enduring success.

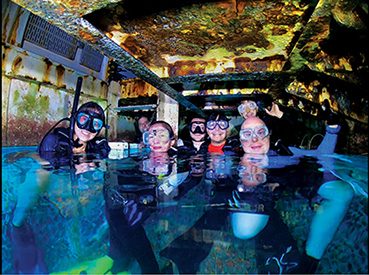

We surfaced in the Aquarius moon pool that morning, and I swiftly stowed my dive gear, eager to exit the water and dry off. It had been my second dive into Aquarius, and the increased pressure upon taking my first breath was familiar. My voice also took on a slightly higher pitch, a subtle result of the increased pressure on my vocal cords.

I had previously spent more than 48 hours in the Jules’ Undersea Lodge at a depth of 21 feet (6.4 meters). While Aquarius and Jules’ maintained higher oxygen levels than the surface atmosphere, I hadn’t felt the pressure change in the lodge. The difference in Aquarius was a constant reminder of the extreme environment surrounding us.

When all the students were ready, the Aquarius operations director and course instructor, Roger Garcia, signaled the start of the simulation. We wasted no time assuming our designated roles. As the lead, I nodded a “go” to Sergey, who seamlessly executed the task of shutting off the external oxygen lines while demonstrating his expertise and calm demeanor.

The minutes ticked by as we performed with a mix of adrenaline and careful coordination. We worked together as a team, communicating clearly and efficiently to overcome each obstacle. A sense of accomplishment washed over us as we concluded the simulation with a successful evacuation. We gained a deeper appreciation for the complexities and challenges of maintaining a habitable environment in the ocean.

The simulated underwater scenario tested our teamwork and attention to detail. We carefully followed each step, earning praise from our instructor for our precision and focus. I was lucky to be the one to close the hatch to the habitat as we exited. I rotated the mechanism, using all my weight to secure the barrier between the habitat and the moon pool area. A diver from the boat surfaced in the moon pool, reporting that our rescue team was here to escort us back to land. We would all stay a few feet underwater on a line until the team could safely bring us up and into the chamber on the boat.

Beyond the simulated environment, we embarked on a series of dives to Aquarius. Submerged in the ocean’s depths, it has become an integrated part of its surroundings and acts as a small artificial reef that hosts a marine ecosystem.

While Aquarius offers the ability to extend a diver’s time at depth for scientific or extreme environment training, people still need the ability to transfer into that environment. Surface-supplied diving (SSD) allows Aquarius aquanauts to perform long dives without needing to switch tanks or deal with the complications of a rebreather. Our SSD introduction course had three phases, culminating in an open-water dive. We honed our SSD skills under expert guidance, and each person played a crucial role in supporting the diver during open-water dives.

After I performed a dive using surface-supplied air to assemble a small configuration of hardware parts, I became the line tender, guiding the umbilical through the currents while ensuring a steady supply of air and communication to the next diver.

Aquarius holds special significance for me, as it evokes memories of my first dives in Florida and my subsequent involvement in coral restoration efforts over the past five years. The Florida Keys had become somewhat of a second home, with familiar faces, local restaurants, and favorite dive sites.

There were no words to capture the feelings of loss, deep sadness, and coming change during the unprecedented temperatures this past summer. I wasn’t surprised to see the corals’ highlighter-hued blues during our first dive to Aquarius. Some were already bright white, indicating genotypes that were more sensitive to the temperature shift. An octopus had nevertheless found solace in the crevice between a window and port cover to sleep, and some corals, sponges, sea fans, and fish had made Aquarius their home as a testament to their adaptability.

Like the space shuttle and the ISS, Aquarius will not be around forever. The course emphasized that we need to study cases like Aquarius to be able to thrive in extreme environments and not just survive. We need to learn from those who designed it and who lived and worked there.

About Aquarius Reef Base

Aquarius Reef Base is uniquely positioned to provide students with opportunities to enhance their content knowledge and receive university training in marine science, dive technologies, dive medicine, and recompression chamber operation. These courses develop career-ready skills, and some align with current dive industry certifications. They strengthen student competitiveness on their college-to-career pathway.

Many courses offer an online-only option that particularly appeals to educators and lifelong learners seeking to augment their teaching or deepen their knowledge without needing hands-on experiential activities. For more information, visit environment.fiu.edu/aquarius/.

Explore More

Learn more about Aquarius Reef Base in these videos, and take a virtual dive with Underwater Earth.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2024