The Serengeti of the Sea Turns 30

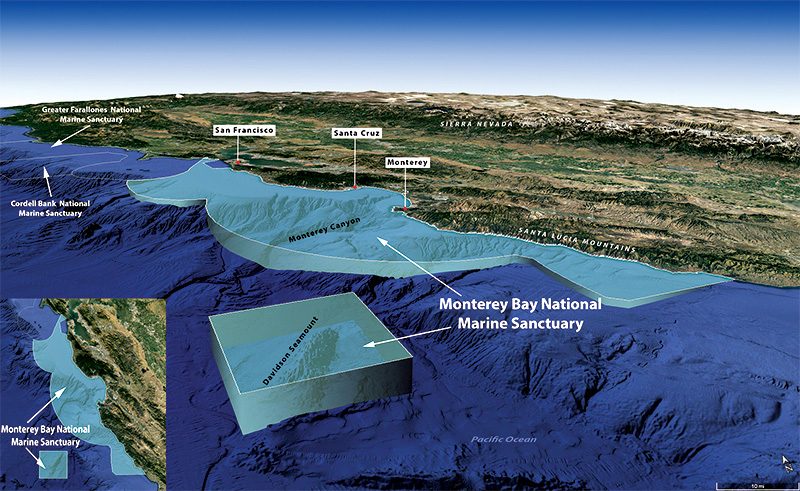

Within the geographical confines of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS) is one of the world’s most ecologically diverse coastal marine environments. The sanctuary boundary spans almost 6,000 square miles (15.540 square meters) and contains more than 276 miles (444 kilometers) of California shoreline.

A massive underwater canyon — deeper than the Grand Canyon and comparable in size and length — starts in the deep waters far beyond the sanctuary boundary and comes into the center of Monterey Bay. Every spring the wind blowing along the California coast stimulates the cold water to upwell from the deepwater canyon, pulling up nutrient-rich water from the darkness, exposing it to the sunlight, and depositing it into the heart of the bay.

This process fuels a sustenance explosion up the food chain, causing species to flock to the region in a yearly migration and churn the waves in group feeding frenzies. Writhing masses of sea lions, dolphins, and whales, matched in fervor by birds diving in from above, create a scene that is awe-inspiring to behold.

Twenty-six species federally recognized as threatened or endangered reside in or migrate to the sanctuary, drawn from far away by more than just the spring upwelling. In the summer, critically endangered leatherback sea turtles arrive after their nine-month, 7,000-mile (11.265 kilometers) journey from nesting beaches in Indonesia. Each turtle in the sanctuary feasts on up to 50 jellyfish per day before completing their feeding cycle and initiating the nearly one-year migration home to nest.

Like the Serengeti National Park in northern Tanzania, which is well known as the site of the largest annual land animal migration in the world, it is no surprise that the Monterey Bay sanctuary is referred to in name as its aquatic counterpart due to the number and diversity of animals you can see in the bay on any given day.

Now a place where marine life and humans can coexist, MBNMS provides us with the opportunity to curb our natural instinct to dominate and consume the environment around us. But for this area of the U.S., that mindset was not always the case.

The history of Monterey Bay and its adjacent coastlines is a history of human environmental exploitation. The 1849 gold rush ushered in a mass migration of prospectors ready to tear apart the hillsides in search of the precious metal. Many of the people who failed went into the existing fur trade, trapping sea otters for their pelts, while others chased elephant seals in the surf for their blubber. Both species nearly became extinct in the process.

Then there were those who ventured out to deeper water to pursue whales, whose oil served as the energy source of the time. A year after the gold rush began, the commercial whaling industry started in Monterey, with whaling stations dotting the coastline until 1921. Coastal residents would flock to the beaches to watch the whalers being towed back and forth across the bay by the harpooned deepwater creatures as they tried in vain to escape their pursuers.

The coastal region’s seemingly limitless bounty proved otherwise when the otters, sea lions, and whales disappeared, and the bay became a watery desert. Residents simply moved on to the next marine economy: harvesting giant California red abalone, the world’s largest abalone species. A year before the last whaling station closed, nine different abalone companies operated along the current sanctuary’s coastline, gathering abalone all day and shipping it worldwide.

When the abalone supply dwindled, the sardine industry exploded, leading to the region’s famed Cannery Row and Monterey becoming known as the sardine capital of the world. But that title lasted for only a few years. In the late 1940s the local industry collapsed when the sardine bounty was exhausted. This, in conjunction with the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill that occurred approximately 250 miles (402 kilometers) down the coast, made many residents realize the impact of different industries on the local ecology.

When politicians and oil industry executives set their sights on Monterey Bay for oil, gas, and mineral exploration and extraction, conservation efforts that had existed only at the grassroots level for decades began to grow exponentially. Central California coastal communities rallied together and, with the leadership of local hero politicians, took the issue to Congress after years of legislative battling. The combined efforts of everyone involved helped Monterey Bay achieve national marine sanctuary status in 1992, a designation it has held for 30 years.

What is the sanctuary after these 30 years?

It is a conservation success story. Since the establishment of MBNMS, the ecosystem has recovered and species populations have returned from their historically low levels and are continuing to thrive under strong protection efforts. With the preservation of public access to beaches and coastal waters, Monterey Bay is a place of social catalyst where people gather together — whether it’s beachgoers combing through rocky tide pools, surfers hitting the waves at the legendary Mavericks surf break, or scuba divers navigating through lush kelp forests, coral reefs, and canyon walls encrusted with colorful marine life.

It is a place of discoveries, such as the thousands of deepwater octopuses found laying their eggs 2 miles (3,2 kilometers) beneath the surface in the dark nooks and crannies of the Davidson Seamount area, which became part of the sanctuary in 2008. MBNMS has 463 reported shipwrecks within its waters — such as the legendary USS Macon airship and its yellow- and blue-winged Sparrowhawk biplanes sitting 1,500 feet (457 meters) below the surface — with more waiting to be discovered.

It is a place of economy, where billions of dollars in revenue are generated each year. Once the whale-killing capital of California, Monterey Bay is now the whale-watching capital, generating more money than whale-hunting ever did. Fisheries for abalone and sardines still exist, and the bay is source to one of the world’s top markets for squid. Enforced regulations ensure that overfishing of the bay’s resources won’t occur again.

It is a place of science, acting as a living laboratory for research to enhance our understanding of the oceans and to help us make informed management decisions. Eleven years after the 1987 outbreak of amnesic shellfish poisoning in humans in Canada, the Monterey Marine Mammal Center discovered the domoic acid toxin in the sanctuary’s sea lions, which consume the same fish harvested by people in the bay. They created a reporting chain for public health officials to help map toxin outbreaks and close harvesting locations. When animals are identified with the toxin, fisheries in the affected areas can be regulated by ramping up testing followed by preventative measures.

It is a place of growing concern. The marine sanctuary encompasses no dry ground, with the shoreward boundary extending no further inland than the mean high-tide line. The coastline of the sanctuary is vast, encompassing dense urban zones and four major shipping ports frequented by international vessels. Approximately 8 million people live within 50 miles (80,5 kilometers) of the sanctuary shoreline, and thousands of square miles of coastal watersheds adjacent to the sanctuary drain waste disposal directly into the sanctuary’s wetlands and marine waters.

Plastic concentrations in the water exist at varying densities at all levels in the water column, from the surface all the way down to 1,000 meters. A 2022 Stanford University study suggests that blue and humpback whales in the Monterey sanctuary may eat 10 million pieces of microplastics — as much as 95 pounds (43 kilograms) — per day. The data is so new that researchers are still uncertain of the future effects on whales and people, but the ramifications of plastic in the ocean have historically been less than ideal for marine animals.

MBNMS is more than just an environmental stronghold. It stands as a model of sanctuary success for the U.S. and inspires marine conservation efforts across the world. Thirty years as a national marine sanctuary is a victory, but it is only the beginning when compared with nearly two centuries of negative human impact on the waters within its boundaries. Some people believe the sanctuary is now in its most vulnerable state, not only from the studied effects of mankind on the environment, but also for the false sense of protection in perpetuity without any need for further action.

An enduring human effort is required to retain the meaning the name sanctuary intends to convey. Threats to the sanctuary are always on the horizon in the form of climate change, coastal development, pollution, and energy needs. MBNMS requires continued funding and support so it can continue to preserve and protect the natural and cultural resources and qualities of the ocean and estuarine areas within its boundaries.

Explore More

To support efforts to conserve the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, go to montereybayfoundation.org

See more of Monterey Bay in these live webcams.

https://elephantseal.org/live-view/

© Alert Diver — Q1 2023