Sustainable Superiority

I WAS READING SYLVIA EARLE’S FOREWARD TO Our Ocean, Our Future: Palau, a lovely coffee-table pictorial book by Michael Aw, David Doubilet, and Jennifer Hayes. Earle opened by remarking on when she’s asked about the best place to go diving. Her usual answer is, “Almost anywhere, 50 years ago.”

My go-to reply when asked the same question typically begins by inquiring if they mean by liveaboard or a time machine. Our similar responses reflect the harsh reality that we’ve seen an alarming degradation of coral reefs in our short lives as traveling divers.

I pondered what I’d see when revisiting Palau. When I first began international dive travel, I used to go to Palau every couple of years, but time and habits slipped away. I was surprised to find the conspicuous absence of a Palau folder in my digital archive, which meant that I hadn’t visited there since my 2001 conversion from film to digital. There has not been another destination I was so past due to revisit.

Against the global backdrop of ocean wildlife’s fight against industrial fishing practices, which Earle also highlights in her introduction, the people of Palau have been incredibly progressive. In 2009 Palau became the first country in the world to protect their sharks with a national shark sanctuary in their exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The effort ended all commercial shark fishing in more than 200,000 square miles of ocean. A year later, then-President Johnson Toribiong announced an expanded sanctuary status that included marine mammals, thereby protecting dolphins, whales, and dugongs.

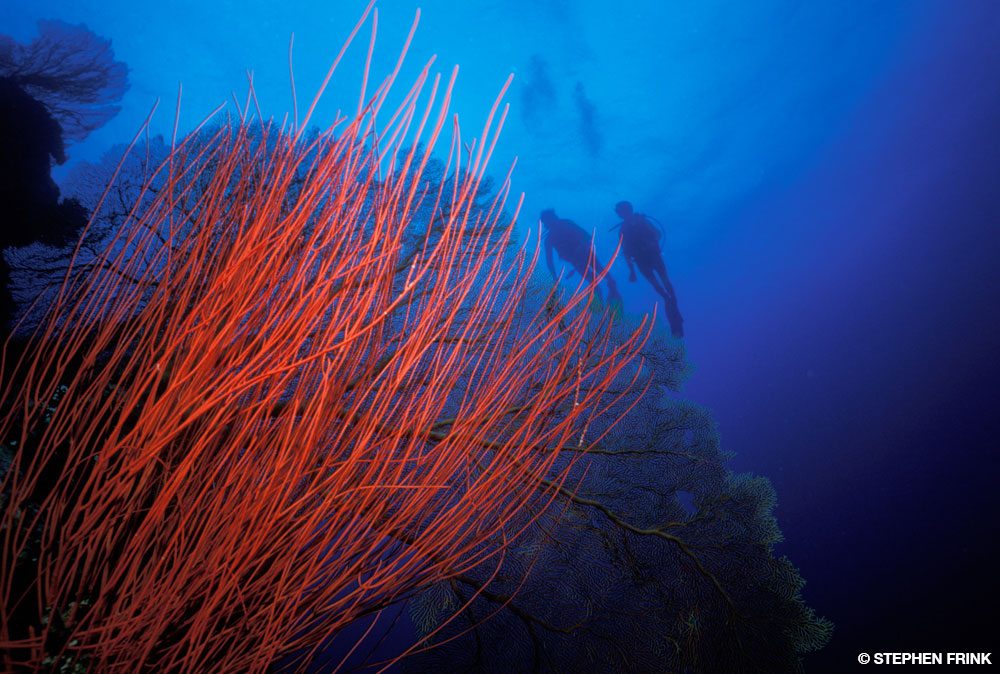

© STEPHEN FRINK

The most ambitious conservation initiative was the Palau National Marine Sanctuary (PNMS), which bans all extractive activity — including industrial and artisanal fishing — in 80 percent of the EEZ, an area larger than California. President Tommy Remengesau Jr. signed the law in October 2015, and since its implementation on Jan. 1, 2020, no other country has assigned marine protected status to such a significant proportion of their national waters.

The efforts are working. The reefs and marine life I saw this year were better than anything I recall from the mid-1990s. I have no empirical baseline, just memory. Factors contributing to Palau’s coral health include geographic luck that the prime reefs are far offshore from the general population centers, the cleansing effect of ocean currents, national conservation efforts, and respectful divers.

Another facet we can’t ignore is the improvement of the dive product. The dive operators have become skilled at watching tides and lunar phases to accurately predict the right times to dive their reefs. They also know when to visit specific reefs to ensure divers can observe episodic behavioral phenomena such as spawning.

Déjà Vu but Better

Traveling to Palau is a bit of a slog from North America; most travel options pass through Guam and entail long transit times. We weren’t terribly disappointed to have an easy dive on the afternoon of our arrival to mitigate jet lag and fatigue. It still provided interesting photo opportunities and reflected evidence of the fierce fighting that these islands endured during World War II.

Pacific islands were strategically important in early 1944 because they protected areas the Japanese occupied in the Philippines, Malaysia, Borneo, and the Dutch East Indies. Palau and nearby Peleliu were targets of relentless U.S. airstrikes, which sank more than 60 Japanese ships. Japan salvaged at least 27 wrecks to help pay their war reparations, but a considerable portfolio of historical ships remain for diving.

These waters also hold many aircraft. Some sank after aerial dogfights, some from being strafed while at harbor, and some from bad luck, which seems to have been the case with the “Jake” seaplane. Resting at 45 feet, just 10 minutes from the Koror dock, its wreckage does not have any bullet holes to indicate aggression or a bent propellor from striking the ocean surface at speed.

A local fisher first spotted the plane’s outline on the seafloor in 1994 and informed a local dive shop. Paul Tzimoulis and Geri Murphy took the first underwater photos of it while they were in Palau to shoot a Skin Diver magazine article. It’s a beautifully intact aircraft sitting in a vast field of hard corals and festooned with colorful encrusting sponges. The visibility on our dive was only about 25 feet, but the sponge cloaking the propellor exploded with color under a bit of strobe light.

By Land or by Liveaboard

For this trip I hosted my group on shore, but previously I had dived Palau from a liveaboard. There are pros and cons to each option.

The daily trips leave Koror in the morning and run 45 to 50 minutes through the protected and scenic Rock Islands to Palau’s iconic dive sites. Most boats do three-tank dives with a lunch break on the beach of a nearby island. Several of these islands have infrastructure, such as picnic tables and restroom facilities, making a day at sea less of a hardship — and you need some time to offgas anyway.

The liveaboards take divers to the same sites but can easily offer four dives per day because they can moor close to the dive sites. Night dives also are easier to stage.

The decision about which option is better for you is more about lifestyle preference than the dive portfolio. Even Peleliu diving is possible from land, but it is a longer run and much easier from a liveaboard.

Piscine Parades

Our first morning’s speedboat ride takes us 27 miles (43 kilometers) southwest of Koror to New Drop-Off. The crew tells us that currents can be strong at the site, but we arrive at slack tide and are treated to a very mellow dive. The reef starts only a few feet under the surface and is part of a vertical wall that runs the entire length of Ngemelis Island.

The wall is nicely decorated with large, colorful sea fans and clusters of pyramid butterflyfish that exasperate me, because I can never get near enough for the close-focus, wide-angle shots I envision. The schools of snappers and barracudas are far more tolerant of my approach.

If the current were running, we would have used a reef hook to hold a position at the second corner along the wall and wait for the gray reef sharks to pass near. That’s their typical protocol, but the variable conditions always define the dive in Palau.

We went to nearby Dexter’s Wall for our next dive, where we found an exceedingly calm cuttlefish impervious to our proximity. The bottom features are similar at many of the wall sites here, including the famous Blue Corner, which is only a few hundred meters away.

New Drop-Off is so good you will likely visit it a few times during a week’s dive itinerary. Our second dive there later in the week was absolutely worth it when we saw abundant turtles along the top of the wall in only 15 feet (24 meters). Those with their eyes away from a viewfinder long enough to see the entire spectacle counted 18 green sea turtles in the shallows. They were so docile that I later commented to our divemaster that they were much more approachable than the ones we saw on subsequent dives in Peleliu. She wryly winked at me and asked which island I thought had a tradition of fishing for turtles.

Blue Corner is the most famous dive in Palau, and it is undoubtedly impressive, but it is dramatically different depending on the current. Currents can suddenly change direction horizontally or vertically, so the divemasters instruct divers to tether to a bit of rocky substrate with a reef hook and slightly inflate their BCDs to lift off the bottom and avoid affecting living coral.

The intense current has scarified the top of the reef, so the procedure is more ecologically benign than it sounds. Hooking in lets divers hover in place without exaggerated motion that might scare away the sharks. Skilled divers and the right current can allow proximity to gray reef sharks, a highlight of the dive.

Immense bumphead parrotfish and large schools of blueline snappers also aggregate here. Napoleon wrasses are common, and you can be rewarded with massive schools of bohar snappers if the lunar cycle is right. Most weeklong itineraries provide multiple dives at Blue Corner due to popular demand for the diverse piscine parade.

The pantheon of the world’s top tropical dives includes Ulong Channel, which is unique among Palau sites. This shallow channel through Ulong Island’s reef structure has a bottom of no more than 45 feet (14 meters) and coral and marine life in little holes that speckle the bottom and slopes along both sides. Sometimes the current is swift, and at other times you gently fin along the bottom during slack tide.

Divers usually drop to 60 feet (18 meters) just north of the channel, which is a good spot for gray reef sharks. The incoming current funnels into the channel and presents a nice opportunity to photograph the sharks against a coral background rather than the deep blue backgrounds at most other wall sites.

The dive’s defining feature is the massive cluster of lettuce corals vertically following the reef slope’s contour for almost 25 feet (7,6 meters). It’s not only the coral itself that makes it so compelling, but also the countless small squirrelfish and damselfish that occupy all the little nooks and crannies of this large coral condominium.

Bumphead Parrotfish Spawning

This spawning event at Grassland might have been a secret at one time, but seeing 11 boats converge here so early in the morning suggests the word is out. The largest known spawning aggregation of bumphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum) happens with a monthly lunar phase if the tide and temperature are right.

As large numbers of bumphead parrotfish mill about in the shallows, anticipation builds in both the observers and the fish. The parrotfish move out to the sand bottom at about 80 feet (24 meters) as a curiously cohesive whole and then rush upward, females cheek-to-cheek with the males. In a synchronized explosion, they release their eggs and sperm. Imagemakers have to be at the right place at the right time to capture this dynamic dance of procreation.

I think about all the well-known spawning aggregations and ponder how few are truly protected. One pass with a purse seine net could wipe out a generation of fish, but thanks to the conservation conviction of the Palau government and the Palau dive fleet’s ongoing vigilance, this spawn is secure for now.

Plan ahead if the bumphead spawning is part of your Palau wish list. Your dive operator will know when it will happen and can help you refine your dates. We did it on two consecutive days and were more productive on the second day after learning the event’s rhythm.

Manta Mecca

In 1905, while Palau was a German colony, Germany realized the value of harvesting guano deposits from the seabirds on Angaur Island because of its commercial value as a fertilizer due to its high phosphate content. To efficiently get the cargo to port for shipping back to Europe, a channel had to be excavated between Ngemelis and Ngercheu islands. German Channel is now so shallow in some places that only speedboats with shallow drafts can navigate it with confidence.

Underwater, the channel has become a manta mecca due to several cleaning stations at just 45 feet (14 meters). The dive guides know where to position divers, and it typically doesn’t take long before mantas will queue up for their daily dose of hygiene. They are indifferent to the presence of divers, and proximity is probable for anyone patient enough to kneel in the sand and wait.

We dived German Channel several times, so the novelty of getting close to a manta faded over the week. But late one afternoon we were treated to a remarkable frenzy of bohar snappers, rainbow runners, and manta rays as they converged to feed on a plankton-enriched current flowing through the channel. All the action happened in the top 20 feet (6meters) of water, with the mantas making loops with their mouths agape and the massive schools of snappers greedily chomping away. We hoped for a repeat but never again had that synergy of conditions during our time on location.

Back at Peleliu

The last time I had dived Peleliu was at a site called Peleliu Express when I was much younger and less savvy about navigating extreme currents. I recall being alarmed when we were all swept off the wall to offgas in the open ocean. The dinghy driver was not surprised, and while the boat was a speck in the far distance by the time we popped our safety sausages, the pickup was routine.

With that dive still on my mind 30 years later, we opted for the more sedate Peleliu dives at Peleliu Wall and the shallow reefs of Coral Gardens. Peleliu Wall was worth the trip from Koror for the colorful sea fans and soft corals adorning the drop-off and bathed in outstanding water clarity. It wasn’t as fishy as the more traditional sites off Ngemelis Island, however, and the marine life was noticeably more skittish.

Coral Gardens offered excellent boulder and branching hard corals; while most were quite pristine, there was also evidence of coral bleaching in the staghorns. One day in a week’s itinerary is likely enough for Peleliu. It’s a good site to experience, but there are many other options.

Coral Gardens offered excellent boulder and branching hard corals; while most were quite pristine, there was also evidence of coral bleaching in the staghorns. One day in a week’s itinerary is likely enough for Peleliu. It’s a good site to experience, but there are many other options.

Discretionary adventures in Palau usually include snorkeling in Jellyfish Lake, but we learned that the populations of golden jellyfish (Mastigias papua etpisoni) were underwhelming. Check with your dive operator for up-to-date information, but with the $100 snorkeling permit fee and the population decrease, we opted out of what is normally a highlight of any Palau adventure.

The Palau Visitors Authority explained that the lake is sensitive to El Niño and La Niña weather patterns, which can affect the wind and rainstorms that help keep the lake cool. While we were there, La Niña was contributing to a water temperature too high for normal golden jellyfish reproduction. The weather will eventually be favorable for their life cycle again, and local knowledge will help inform visitors when it is right to add the activity back to your plans. AD

How to Dive It

Getting there: Your international flight will arrive in Koror, and U.S. citizens staying less than a year don’t need a visa. Various fees are associated with diving Palau, including the dive permit ($100) and additional permits to dive Peleliu ($30) and snorkel Jellyfish Lake ($100).

Conditions: Water temperatures are fairly consistent year-round, usually ranging from 82°F to 86°F (28ºC to 30ºC). The drier season is from December to April, but an aerial view of the verdant Rock Islands reveals that rain is common throughout the year.

Explore More

See more of Palau’s pristine beauty in this video and Stephen Frink’s bonus gallery.

© Alert Diver — Q3 2023