Holistic reef maintenance for Mission: Iconic Reefs

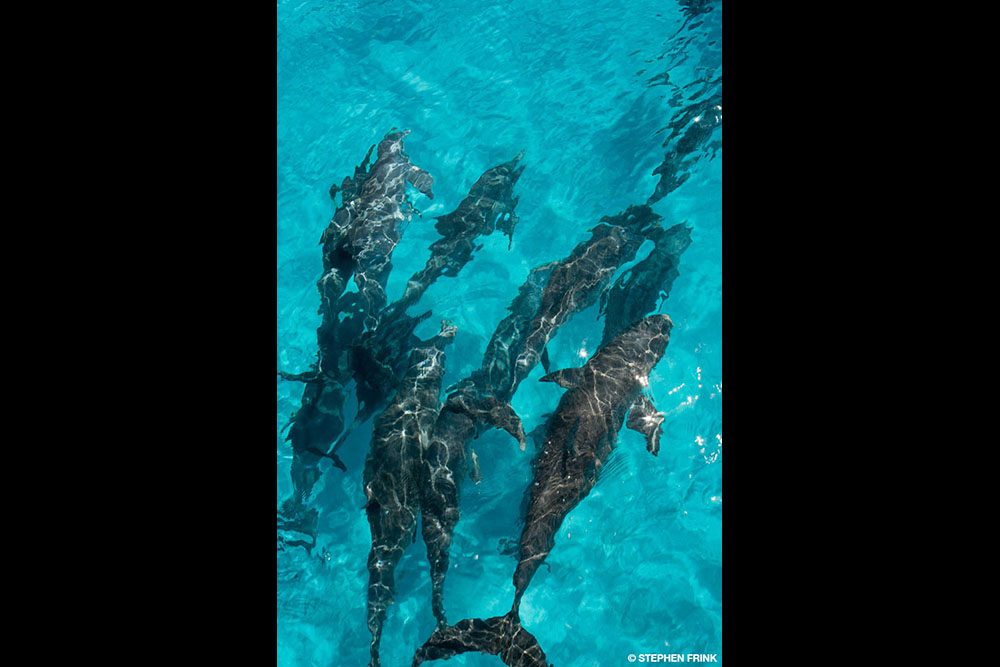

In late 2019 the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and a cadre of state, federal, university, and restoration practitioner partners launched Mission: Iconic Reefs (MIR), a two-phased, 20-year, ecosystem-scale restoration initiative for the Florida Keys that focuses on restoring seven high-value, iconic reef systems.

Selected restoration sites are located along the main offshore bank barrier reef system, midchannel patch reefs, and nearshore reefs, with a regional distribution encompassing the Upper, Middle, and Lower Keys. Chosen for their relative health, the likelihood of restoration success, ecological connectivity, geography, and ecosystem services, these seven reefs represent the most ecologically and economically significant sites.

Unlike previous restoration efforts, MIR involves a comprehensive ecosystem restoration strategy beyond coral outplanting. Site preparation and substrate conditioning remove nuisance algal and invertebrate species and expose the underlying crustose coralline algae (CCA) colonized reef framework before any coral transplanting occurs. A maintenance program eliminates marine debris, removes coral predators (corallivores), controls nuisance species of algae and colonial invertebrates, and rescues and reattaches dislodged corals. Herbivorous urchins and crabs that are reintroduced to the site help control algal cover.

Similar to tending a vegetable garden, trained coral gardeners must prepare a site for outplanting by removing the underwater version of weeds — fleshy algae, encrusting invertebrates, cyanobacteria, gorgonians, and sea fans — to allow the coral fragments to attach successfully. Trained divers visit each restoration site weekly or monthly, tending the corals through weeding, providing pest control, pruning dead branches, collecting coral-eating snails and worms, removing diseased coral colonies and fragments, and reattaching dislodged coral fragments.

Recognizing this is a time-intensive process, NOAA is establishing a workforce of professional and volunteer divers who will serve as gardeners on these reefs. The most crucial aspect of their maintenance involves collecting coral-eating snails and fireworms, which tend to accumulate at the base of the restored fragments and larger colonies. These predators are responsible for more chronic tissue loss and coral mortality than any other factor and can affect corals of any size or age at any time after transplantation onto the reef. They also gather on wild corals.

Recently fragmented corals release mucus containing chemicals that Coralliophila snails can smell. This attracts the snails and may help them find and colonize new outplants within a few days. Once snails arrive on a coral, they consume tissue at the colony’s base and slowly eat their way toward the branch tips. When coral dies, snails move on to the next closest coral in the plot, ultimately consuming all the living tissue on surrounding corals unless their populations are controlled.

The unusual biology of coral-eating snails is one of the reasons for their success. These sex-changing mollusks start as male when small and form aggregates of two to more than 50 snails per coral. Ultimately, the largest individual in an aggregation will change from male to female, and more will become female over time. These females brood their egg cases internally throughout the year, and each female produces tens of thousands of fully developed baby snails with each brood. Coralliophila typically achieves a larger size on elkhorn and staghorn corals than on massive and boulder corals. These larger snails eat more coral and produce far more offspring than a small female snail.

Removing coral-eating snails is relatively simple, but divers must have good buoyancy to avoid breaking the coral branches, and they need to develop a search image for the snails, which can be hard to spot when algae overgrow their shells. A trained coral gardener can remove several hundred snails across thousands of restored corals on a typical dive.

Other corallivores, especially fireworms, are even harder to locate, because they typically feed on branch tips at night and find refuge within the reef during daylight. In habitats that support large fireworm populations, scientists are exploring other options for removal, such as small wire mesh cages baited with food and pheromones.

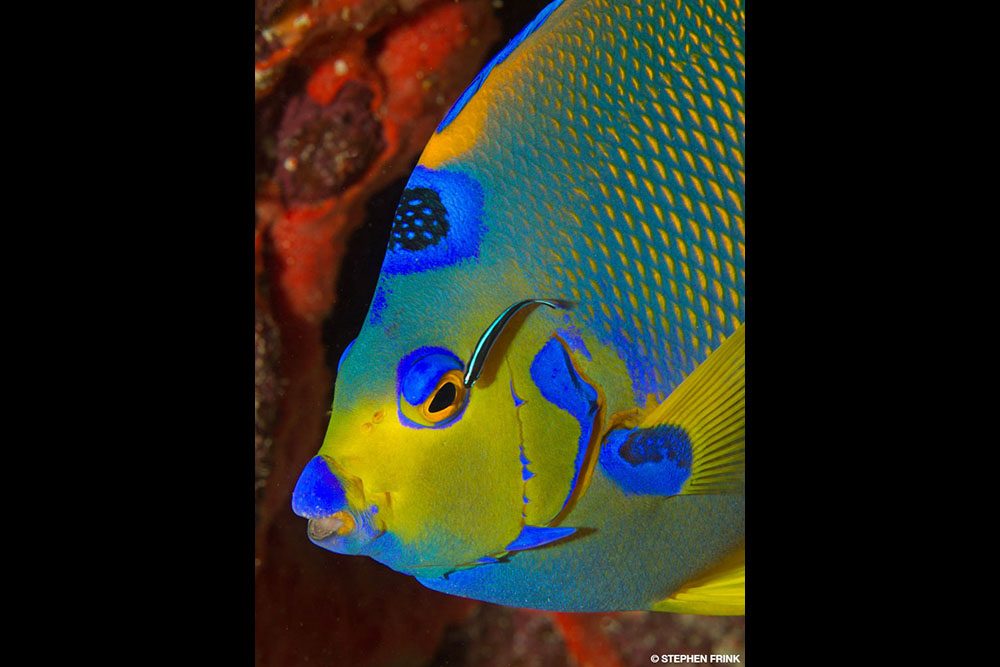

These measures can help reduce the amount of tissue loss associated with predation, but a more sustainable, long-term solution may require restocking important predators of these coral-eating invertebrates, including certain fishes, lobsters, and other keystone species.

As coral declined from roughly 30 percent living cover in the early 1980s to less than 2 percent, we have witnessed a phase shift with nuisance species such as turf and fleshy macroalgae, the golden-brown colonial anemone Palythoa caribaeorum, sea fans, and branching gorgonians (soft corals). They all have colonized open areas on the reef, spreading across the bottom, monopolizing substrates, and preventing the settlement and survival of new corals.

Palythoa is most problematic, especially in shallow reef crest and spur and groove areas, where it can cover all of the bottom and grow over surviving boulder and plating corals. These habitats formerly supported dense thickets of elkhorn and staghorn corals — species that are now the focus of the first phase of the MIR restoration initiative. Palythoa has few natural predators because it is highly toxic to marine invertebrates, fishes, and humans. The current removal methodologies of using carbide paint scrapers, wire brushes, rock hammers, and chisels are slow and laborious. The process requires extreme care to capture all the colonial anemone polyps so they don’t immediately recolonize the cleaned areas. Coral gardeners need to wear gloves to protect themselves from Palythoa toxin exposure.

The National Marine Sanctuary Foundation funded the development of a prototype vacuumlike tool to assist with removing Palythoa, algae, and cyanobacteria. Using it is more effective and efficient when preparing sites for outplanting and maintaining outplants, which increases the likelihood of survival. The tool, which a crew operates from a small vessel, includes a trash pump to create suction, a 55-gallon drum with an integrated filter similar to a French press to contain the biomaterial, and a long (150-meter) neutrally buoyant hose and tool head. It has different sizes of funnels to focus or diffuse the suction, it can have either attached scrapers or a wire brush, and it works in combination with other hand tools. The goal is ensuring the collection of nuisance species without partially dispersing them into the water column.

Pilot efforts to remove algae, invertebrates, and coral-eating snails have proven effective at improving the restored corals’ survival, but it is labor-intensive work that requires a long-term commitment. The intent is to jump-start reef recovery by providing the corals with a balanced ecosystem that becomes sustainable without continued intervention. To help with this goal, NOAA and its partners are exploring options to reintroduce herbivorous sea urchins and Caribbean king crabs.

The Diadema antillarum urchin is a keystone herbivore that experienced a mass die-off in the mid-1980s that reduced its population by 90 to 98 percent, and only limited recovery of the species has occurred in Florida. University partners are developing the appropriate mariculture methods to raise enough Caribbean king crabs (Maguimithrax spinosissimus) and Diadema urchins and are using novel larval collectors to successfully settle larval urchins from the water column. Pilot studies hope to improve urchin retention and identify the level of site affinity, microhabitat preferences, and amount of shelter needed within these habitats. Finding the appropriate density will reduce the amount of fleshy and turf algae and improve habitat quality.

The number of coral species in propagation, corals returned to the reef, and techniques to outplant them have greatly improved. We have identified corals that are more tolerant of climate stressors, but short-term mortality rates of these restored corals remain high, and their long-term persistence is limited, primarily due to natural biological factors that can be more proactively addressed.

The most critical step of this management centers around adopting and implementing a comprehensive stewardship program involving trained divers who tend the coral gardens and remove coral predators, nuisance algae, and invertebrates to support restoration practitioners.

Andy Bruckner is science coordinator for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Explore More

See more of the Florida Keys reefs in a bonus photo gallery.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2023