“Coronary heart disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among adults in both North America and Europe.”

It behooves divers to be aware of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease, especially atherosclerosis, and of specific measures they can take to mitigate them. Atherosclerosis — popularly known as “hardening of the arteries” — is the most common affliction of the heart. Its prevalence increases with age, and it causes premature death in many people. Indeed, it is often assumed to be associated with normal aging. However, the disorder can be prevented — or at least slowed down — and a physically active lifestyle extended well into older age.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about:

- Overview of Cardiovascular Risk Factors

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidemia

- Overweight and Obesity

- Metabolic Syndrome

Overview of Cardiovascular Risk Factors

The most common manifestations of acquired (rather than congenital) cardiovascular disease are coronary heart disease, stroke and peripheral artery disease. Coronary heart disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among adults in both North America and Europe.

The likelihood that a given individual will acquire cardiovascular disease and suffer a life-threatening cardiovascular event depends on many risk factors. Some risk factors — such as family history, gender, ethnicity and age — cannot be changed. Other risk factors are modifiable — including some involuntary health conditions and some lifestyle-related factors. Involuntary conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes can be treated with medication as well as with diet and lifestyle adjustments. Lifestyle-related risk factors include tobacco use, an unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and excessive alcohol consumption — all of which can be voluntarily changed.

It is important to understand that having any of these risk factors does not mean that you will definitely develop cardiovascular disease. However, the more risk factors you have, the greater is the likelihood that you will develop cardiovascular disease — unless you control your involuntary health conditions and adopt a healthy lifestyle.

The following percentages of deaths caused by cardiovascular disease can be attributed to these specific risk factors:

- High blood pressure: 13%

- Tobacco use: 9%

- High blood sugar: 6%

- Physical inactivity: 6%

- Overweight and obesity: 5%

Hypertension

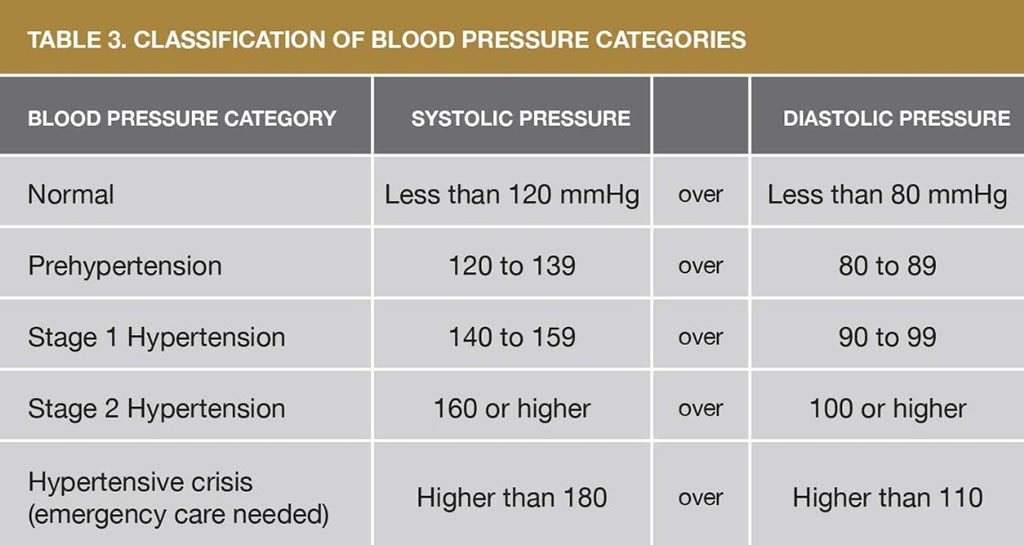

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common medical condition in the general population as well as among divers. Blood pressure is a measure of the force with which blood pushes outward on the arterial walls. A blood-pressure reading is a ratio of two numbers. The top number is the systolic pressure, when your heart is beating, and the bottom number is the diastolic pressure, when your heart is resting between beats. The unit of measurement for a blood-pressure reading is millimeters of mercury, which is abbreviated as “mmHg”; a normal reading is 120/80 mmHg, often referred to as “120 over 80.”

The criteria for a diagnosis of hypertension vary slightly from country to country and even from one reference to another. The table below shows the most common criteria used in the United States.

Statistics

- 78 million American adults (or 31% — almost 1 in 3) have hypertension.

- 69% of those who have a first heart attack, 77% of those who have a first stroke, and 74% of those with chronic heart failure have hypertension; it is also a major risk factor for kidney disease.

- 348,000 American deaths in 2009 were attributed, as either a primary or contributing cause, to hypertension.

- $47.5 billion annually is spent on direct medical expenses related to hypertension.

- $3.5 billion annually is lost in productivity due to hypertension.

- Only 47% (less than half) of those with hypertension have the condition under control.

- 30% of American adults have prehypertension.

Sources: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and American Heart Association

Two kinds of complications face a person with hypertension: short term and long term. Short-term complications generally result from extremely high blood pressure; the most significant is the risk of a stroke (also called a “cerebrovascular accident”) due to the rupture of a blood vessel in the brain. Long-term detrimental effects are more common; they include coronary artery disease, kidney disease, congestive heart failure, eye problems and cerebrovascular disease.

Mild hypertension can often be controlled with diet and exercise; however, medication may be necessary to keep blood pressure within tolerable limits. Many classes of drugs are used to treat hypertension, and they have varying side effects. Some individuals must change medications after one drug appears to be or becomes ineffective. Others might need to take more than one drug at a time to keep their blood pressure under control.

A class of antihypertensive drugs known as beta blockers may cause a decrease in maximum exercise tolerance and may also have some effect on the airways. These side effects normally pose no problem for the average diver. Another class of antihypertensives, known as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, may be preferred for divers, though a persistent cough is a possible side effect of ACE inhibitors. Calcium channel blockers are another choice, but a potential side effect of these drugs is lightheadedness upon going from a sitting or supine to a standing position.

Diuretics — drugs that promote the production of urine — are also frequently used to treat hypertension. Their use requires careful attention to maintaining adequate hydration and to monitoring electrolyte levels in the blood.

Effect on Diving

As long as an individual’s blood pressure is under control, the main concerns regarding fitness to dive are side effects of any medication(s) and evidence of damage to the major organs. Most antihypertensive drugs are compatible with diving as long as side effects are minimal and the diver’s performance in the water is not significantly compromised. In addition, a diver with long-standing hypertension should be monitored for evidence of associated damage to the heart and kidneys.

Divers who demonstrate adequate control of their blood pressure and who show no significant decrease in their performance in the water due to drug side effects should be able to dive safely. However, it is important that such divers have regular physical examinations, including screening for long-term consequences of hypertension, such as coronary artery disease.

Hyperlipidemia

Cholesterol — a soft, waxy substance — is one of the lipids found in the blood and, indeed, in all the cells of the body. Important to the healthy functioning of our bodies, cholesterol is a part of our cells’ membranes and is used in the production of hormones.

The cholesterol in the human body may originate from foods rich in cholesterol — such as meat, eggs and diary products — or it can be made internally by our bodies. The body can also produce cholesterol from foods that do not themselves contain cholesterol but that do contain saturated fat — such as palm oil and coconut oil — or from trans fats — such as fried food in restaurants and commercial cakes or cookies. Cholesterol by itself does not dissolve in blood; it has to be combined with proteins to form soluble lipoprotein particles. Lipoproteins come in two forms: low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

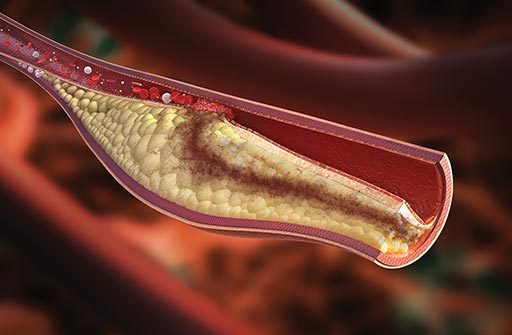

LDL is considered “bad cholesterol” because too much of it leads to a narrowing and stiffening of the arteries due to a buildup of cholesterol, which accumulate in deposits called “plaques” on the arteries’ inner walls. This condition is called atherosclerosis. It contributes to hypertension and causes peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease, heart attack and stroke — as well as erectile dysfunction in men.

In contrast, HDL cholesterol is considered “good cholesterol” because it reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by transporting cholesterol away from the bloodstream and back to the liver, which facilitates its removal from the body. HDL thus helps to prevent the buildup of cholesterol plaques on the walls of the arteries. An individual’s HDL cholesterol level is to some extent a factor of one’s genetic makeup. But HDL levels can be lowered by type 2 diabetes; certain drugs, such as beta blockers and anabolic steroids; smoking; being overweight; and being sedentary. On the other hand, estrogen, a female hormone, raises HDL levels, partially explaining why cardiovascular disease is less prevalent in premenopausal women.

Triglycerides are another factor in hyperlipidemia. Triglyceride is the most common type of fat in the body. Normal triglyceride levels vary by age and sex. High triglyceride levels combined with high levels of LDL cholesterol increase one’s risk of cardiovascular disease.

Your cholesterol level is a composite measure of all these lipids, in either milligrams per deciliter of blood (mg/dL) or millimoles per liter of blood (mmol/L).

Many American experts recommend the following cholesterol levels:

- Total cholesterol: 200 mg/dL (5.2 mmol/L)

- LDL cholesterol: from below 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) to 129 mg/dL (3.3 mmol/L), depending on your health status

- HDL cholesterol: above 60 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L)

- Triglycerides: below 150 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L)

Source: American Heart Association

The American Heart Association recommends that all adults age 20 and older have their cholesterol and other risk factors for hyperlipidemia checked every four to six years and also work with their health-care providers to determine their risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke.

Overweight and Obesity

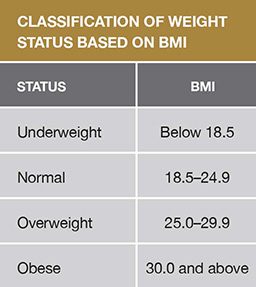

The terms overweight and obesity refer to a body weight in relation to height that is greater than is considered healthy; both conditions often (but not necessarily) result in a higher proportion of body fat, known as adipose tissue, compared with lean muscle mass. Overweight is applied to those with a somewhat elevated weight, and obesity to those who are extremely overweight.

Statistics

- 69% of adult Americans (more than two-thirds) are either overweight or obese.

- Adult obesity rates have more than doubled in just over 30 years, from 15% in 1976–1980 to 36% percent in 2009–2010.

- 10 years ago, the obesity rate was significantly higher among women than men; currently, the rates are essentially the same — within a few decimal places of 36% for both men and women.

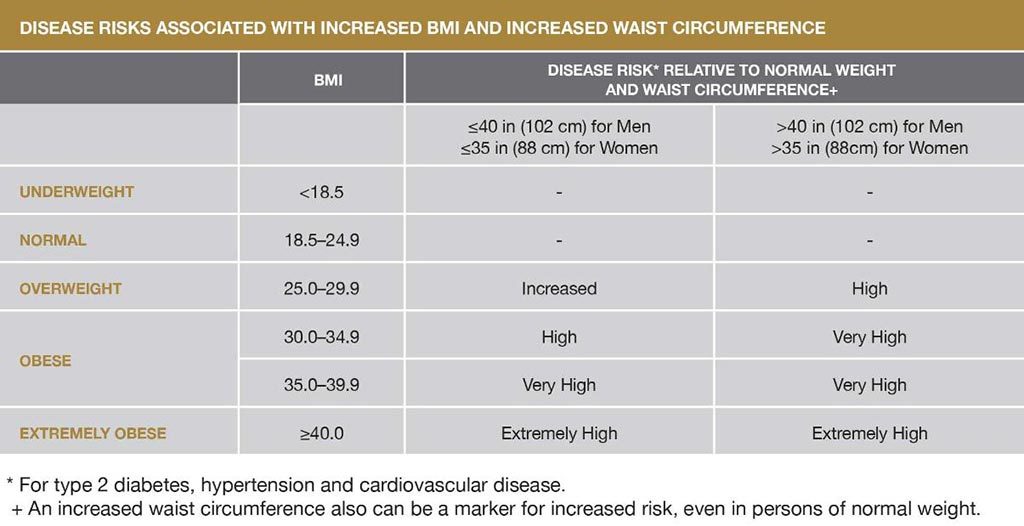

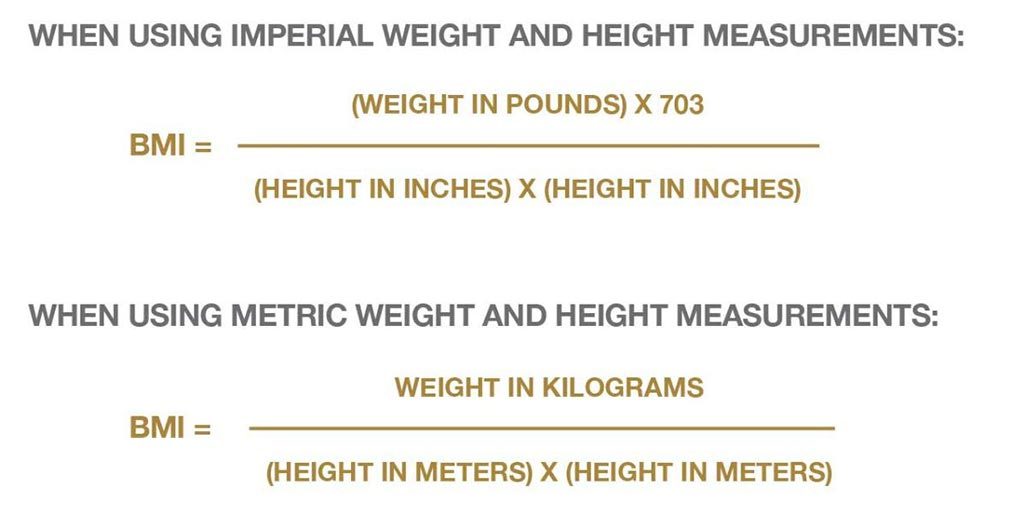

Body mass index (BMI) is a common way of expressing the ratio between weight and height. The following equations are used to calculate BMI:

BMI is an important measure for understanding population trends, but it does have some limitations, as follows:

- It may overestimate the proportion of body fat in athletes and others with a muscular build.

- It may underestimate the proportion of body fat in older persons and others who have lost muscle mass.

Accordingly, BMI is just one of many factors that should be considered in evaluating whether an individual is at a healthy weight — along with waist size, waist-to-hip ratio and a measurement known as “skin-fold thickness.”

Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a disorder that affects how the body uses and stores energy. According to the American Heart Association, a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome requires the presence of three or more of these conditions:

- Abdominal obesity — defined as a waist circumference of 40 inches (102 centimeters) or above for men and 35 inches (89 centimeters) or above for women).

- A triglyceride level equal to or greater than 150 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).

- An HDL cholesterol level below 40 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) for men and below 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) for women.

- A blood pressure equal to or greater than 130/85 mmHg or the use of medication for hypertension.

- A fasting blood glucose level equal to or greater than 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or the use of medication for hyperglycemia.

Metabolic syndrome is associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. Other disorders associated with metabolic syndrome include endothelial dysfunction and chronic low-grade inflammation.

Measuring the circumference of your waist to detect abdominal obesity, meaning more fat is at your waist than at your hips, is a good start in assessing whether you may have metabolic syndrome. This is important because abdominal obesity represents a higher risk for heart disease and type 2 diabetes, and the risk increases progressively as waist size increases beyond the dimensions noted above. The implications of these factors are shown in the chart below.